Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

et MythAmerica Series

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

Meet MythAmerica Series

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

Uncle Sam’s Kids, Part 1

“And a Little Child Shall Lead Them”

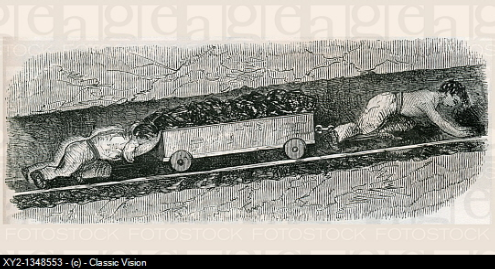

The tunnel was narrow, and a mere 16in high in places. The workers could barely kneel in it, let alone stand. Thick, choking coal dust filled their lungs as they crawled through the darkness, their knees scraping on the rough surface and their muscles contracting with pain.

A single “hurrier” pulled the heavy cart of coal, weighing as much as 500 lb, attached by a chain to a belt worn around the waist, while one or more “thrusters” pushed from behind. Acrid water dripped from the tunnel ceiling, soaking their ragged clothes.

Many would die from lung cancer and other diseases before they reached 25. For, shockingly, these human beasts of burden were children, some only five years old. (Daily Mail)

The year was 1840, the place was Britain.

The description above was not something new in Britain, but it was something that was “out of sight, out of mind” from most middle class and upper class Brits until that year. By 1840 there were enough compassionate people aware and concerned about it—and making a big enough stink about it—to get parliament to sit up and take notice.

In 1840 Lord Ashley, later Lord Shaftesbury, set up the Children’s Employment Commission, interviewing hundreds of children in coalmines, works and factories. Its findings, reported in 1842, were deeply shocking. [ibid]

Before the Industrial Revolution, most poor people in Britain lived and worked on the land. Yes, children worked on the land too under the supervision of their parents, and it may have been a cold, hard life for most. But it was nothing to compare to the totally impersonal cruelty that came with the industrialization of the nation that led to such families being crowded into cities.

Living conditions were appalling. Families occupied rat and sewage-

… The competition for jobs meant that wages were low, and the only way a poor family could fend off starvation was for the children to work as well.

…In these wretched circumstances, an extra few pennies brought home by a child would pay for a small loaf of bread or fuel for the fire: the difference between life and death.

A third of poor households were without a male breadwinner, either as a result of death or desertion. In the broken Britain of the 19th century, children paid the price. [ibid]

This is the England described by British author Charles Dickens in such books as Oliver Twist. That book still resonates with modern readers, and has been made into numerous movies and TV specials.

But the life of the young fellow in the book wasn’t the fantasy output of Dickens’ fertile imagination. It was based on the cold, cruel reality for millions.

While the upper classes professed horror at the iniquities of the slave trade [viewed as the Great Evil of the upstart USA], British children were regularly shackled and starved in their own country. The silks and cottons the upper classes wore, the glass jugs and steel knives on their tables, the coal in their fireplaces, the food on their plates – almost all of it was produced by children working in pitiful conditions on their doorsteps.

But to many of the monied classes, the poor were invisible: an inhuman sub-

Lord Shaftesbury went all over the Kingdom interviewing children who were working in mines, textile mills, and in such jobs as chimney sweeping.

Robert North, who worked in a coal mine in Yorkshire, told an inspector: ‘I went into the pit at seven years of age. When I drew by the girdle and chain, my skin was broken and the blood ran down … If we said anything, they would beat us.’

Another young hurrier [coal wagon puller or pusher], Patience Kershaw, had a bald patch on her head from years of pushing carts – often with her scalp pressed against them – for 11 miles a day underground. “Sometimes they [the miners] beat me if I am not quick enough,” she said.

The inspector described her as a “filthy, ragged, and deplorable-

Others, like Sarah Gooder, aged eight, were used as “trappers”. Crouching in the darkness of the tunnel wall [with cockroaches and rats for company…], they waited to open trap doors which allowed the carts [large coal carts with perhaps tons of coal being pulled by horses or mules] to travel through.

“I have to trap without a light and I’m scared,” she told the inspector. “I go at four and sometimes half-

Most were exhausted by their working hours – they were often woken at 4am and carried, half-

Many young trappers were killed when they dozed off and fell into the path of the carts. Ten-

These were the real David Copperfields and Oliver Twists. Beaten, exploited and abused, they never knew what it was to have a full belly or a good night’s sleep. Their childhood was over before it had begun. [ibid]

Poor families sent their children out to work to supplement their starvation-

Children with no parents and no extended family who would take them in were sent to live-

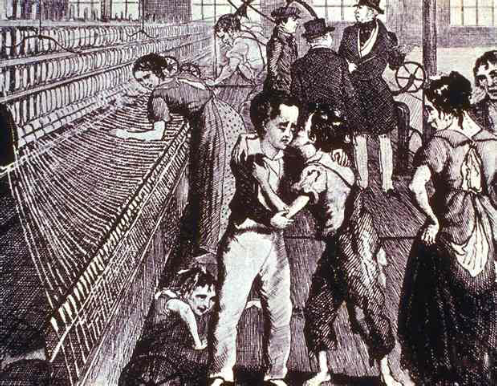

As British productivity soared, more machines and factories were built, and so more children were recruited to work in them. During the 1830s, the average age of a child labourer officially was ten, but in reality some were as young as four.

Children were the ideal labourers: they were cheap (paid just 10-

In exchange for board and lodging, they would work without wages until adulthood. If they ran away, they would be caught, whipped and returned to their master.

Some were shackled to prevent them escaping, with “irons riveted on their ankles, and reaching by long links and rings up to the hips, and in these they were compelled to walk to and fro from the mill to work and to sleep”.

It was also legal at this time to capture vagrant children and force them into apprenticeships: slavery in all but name.

… Supervisors used terror and punishment to drive the children to greater productivity. A boy in a nail-

Yes, there were nasty old cities! Oh, for the idyllic farm life…

But despite the growth of cities, agriculture remained the biggest employer of children during the Industrial Revolution. While they might have escaped the deadly fumes and machinery of the factories, the life of a child farm labourer was every bit as brutal.

Children as young as five worked in gangs, digging turnips from frozen soil or spreading manure. Many were so hungry that they resorted to eating rats. [ibid]

Back in the cities, one of the most dangerous jobs was that of the chimney sweep. No, it wasn’t all it was cracked up to be in the cheery chimney sweep scenes in Mary Poppins! That movie was set in 1910 London. Perhaps by then the average adult “professional chimney sweep” actually did enjoy his job after a fashion.

But in the 1840s the life of a “pauper apprentice” to such a fellow was far from Chim-

When you get your chimney cleaned by a professional chimney sweep, special tools are used which are proven to be effective. There was a time in history, however, in which the job of cleaning a chimney was carried out by a child who would climb the chimney while holding a brush over his head. The soot would fall down over the child and down to the bottom of the fireplace. The child would then slide back down the chimney, collect the soot, and hand it over to the master sweep, who, in effect, owned him. And this isn’t even the worst of it.

Small boys, usually 6 years of age, were purchased from their poverty stricken parents by a master sweep. The children became the property of the master sweeps and were virtually always cruelly treated, essentially living the life of slaves in some of the worst conditions imaginable. [Sweepy Stories]

Why child “chimney sweeps” in the first place? It goes back to the “Great Fire of London” in 1666, when practically the whole city was burned down. Until then, chimneys had been large enough for an adult to go up in and “sweep out” the creosote deposits that built up and were a fire hazard. But new building code rules went into effect after the Great Fire, requiring fireplaces to have narrow chimneys to keep fires from spreading from building to building. And with buildings in the crammed city being tall and narrow rather than spread out, this made for narrow, very tall, and often very winding chimneys. Into which only a small child would fit.

As a result, it became the life of generations of small boys that they were made to wake before dawn and work mercilessly. The children would climb up the chimneys [many did their work naked much of the time] using their elbows, back, and knees. The master sweep would scrub their knees to harden them; but before calluses formed, the children were usually seriously bloodied.

There were many hazards associated with human chimney sweeps. Children got stuck in the 18-

These children received no wages, but they were beaten if they didn’t work well and quickly enough to suit the master sweep. They received little food and usually slept in basements on top of the blackened bags used to collect soot. [The soot was sold as fertilizer by the adult chimney sweep.]

As a result of their work, the children often had lung problems, and their eyes would swell, becoming sore and inflamed. Many children became disfigured or had stunted growth because they were placed in such unnatural positions before their bones were fully formed.

…When the boys became adolescents, it wasn’t unusual for them to suffer from a painful cancer of the scrotum. Chimney Sweep Cancer was unique to chimney sweeps and is the first recorded form of industrial cancer.

Efforts were made through the years to put an end to the cruel practice of using child chimney sweeps, but they failed until 1875. The death of 12-

George Brewster became stuck in one of the chimneys in Fulbourn Hospital. His master, William Wyer, had sent George into that situation. A wall had to be torn down to free George from his narrow prison. He died a short time later. Wyer was charged and found guilty of manslaughter. George Brewster was the last child chimney sweep in England to die in a chimney. [ibid]

Strangely enough, years before that, new, “scientific” chimney sweeping apparatus had been invented that would allow adult chimney sweeps to reach the length of a chimney from the ground or the roof. This should have eliminated the market for young boys for the job. It wasn’t the adult chimney sweeps who insisted on keeping their “pauper apprentices.” It was, instead, by some reports, many homeowners themselves who insisted that the little boys could do a better job than those new-

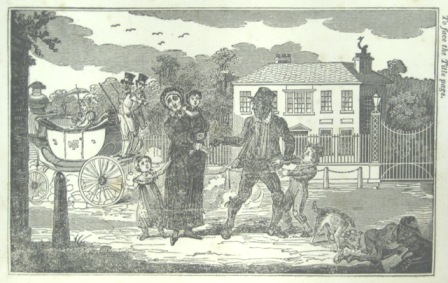

An impoverished mother indenturing her son as an apprentice

to a master-

Although legislation wasn’t introduced until 1840, the campaign against the use of ‘climbing boys’ had first started to gather pace in the first half of the 19th century, with an increasing awareness of their inhumane treatment and the development of alternative mechanical methods of cleaning chimneys. The Chimney Sweep’s Friend and Climbing Boys Album, edited by the radical writer and poet James Montgomery used a mixture of illustrations, verses, true-

Although chimney sweeping was horribly dangerous and miserable, in some ways it wasn’t any worse than work in the textile mills.

Robert Blincoe – on whom Dickens’ Oliver Twist is thought to be based – was sold, aged six, as a ‘climbing boy’ to a chimney sweep in London.

Forced to scale the narrow chimneys, only 18in wide, he would scrape his elbows and knees on the brickwork and choke on coal dust.

It was common for the master sweep to light a fire under them to make them climb faster. Many climbing boys and girls fell to their deaths. After several months, Blincoe was returned to the workhouse. Then, aged just seven, he was sent along with 80 other children to a cotton mill near Nottingham to work as a ‘scavenger’ – crawling under the machines to pick up bits of cotton, 14 hours a day, six days a week.

In return, he was given porridge slops and black bread. Weak with hunger, at night he crept out to steal food from the mill owner’s pigs.

Many child scavengers lost limbs or hands, crushed in the machinery; some were even decapitated. Those who were maimed lost their jobs. In one mill near Cork there were six deaths and 60 mutilations in four years. Blincoe was lucky: he only lost half a finger.

A German visitor to Manchester in 1842 remarked that there were so many limbless people it was like ‘living in the midst of an army just returned from campaign’. A doctor who observed mill workers noted that ‘… their complexion is sallow and pallid, with a peculiar flatness of feature, caused by the want of a proper quantity of adipose substance [fatty tissue], their stature low, a very general bowing of the legs … nearly all have flat feet’. [Source]

Just what were tiny children losing their limbs and sometimes heads over?

The youngest children in the textile factories were usually employed as scavengers and piecers. Scavengers had to pick up the loose cotton from under the machinery. This was extremely dangerous as the children were expected to carry out the task while the machine was still working. David Rowland, worked as a scavenger in Manchester: “The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught.”

John Brown wrote about this in his book, Robert Blincoe’s Memoir (1833): “The task first allocated to Robert Blincoe was to pick up the loose cotton that fell upon the floor. Apparently, nothing could be easier… although he was much terrified by the whirling motion and noise of the machinery. He also disliked the dust and the flue with which he was half suffocated. He soon felt sick, and by constantly stooping, his back ached. Blincoe, therefore, took the liberty to sit down; but this, he soon found, was strictly forbidden in cotton mills. His overlooker, Mr. Smith, told him he must keep on his legs.”

Frances Trollope, wrote about this work in her novel, Michael Armstrong: Factory Boy (1840): “A little girl about seven years old, who job as scavenger, was to collect incessantly from the factory floor, the flying fragments of cotton that might impede the work… while the hissing machinery passed over her, and when this is skillfully done, and the head, body, and the outstretched limbs carefully glued to the floor, the steady moving, but threatening mass, may pass and repass over the dizzy head and trembling body without touching it. But accidents frequently occur; and many are the flaxen locks, rudely torn from infant heads, in the process.” [Source]

There were many other dangerous and exhausting jobs done by young children.

The average height of the population fell in the 1830s as an overworked generation reached adulthood with knock-

… Children in glassworks were regularly burned and blinded by the intense heat, while the poisonous clay dust in potteries caused them to vomit and faint.

…Girls who worked in match factories suffered from a particularly horrible disease known as phossy jaw. [Source]

This was not at all uncommon…

In the 19th century, workers using white phosphorus in the manufacture of matches suffered a condition known as phossy jaw – one of the most frightful occupational diseases known. It began with tooth ache and painful swelling of the gums and jaw. Abscesses formed, accompanied by a fetid discharge which made its victims almost unendurable. The victims’ jawbones would literally rot and glow greenish-

White phosphorus was eventually outlawed in matches, being replaced by red phosphorus which is harmless.

Those most quickly affected were the workers who dipped the sticks into the phosphorus paste. Direct contact with the phosphorus paste may have contributed but the dipping rooms of these factories often were poorly ventilated and filled with dense vapor. But the workers, often children, who dried the matches, ejected them from the drying racks and those who packed the finished product eventually also developed the disease. The condition might develop slowly over years but in its final phase would run a course of 6-

The saddest part of the whole story is that it all need not have happened! It was long known that the other form of phosphorus, red phosphorus, worked just as well in matches as white phosphorus. However, plentiful cheap labor, the absence of industrial health regulations and a profit-

Surely someone noticed all of this and felt compassion for all the pathetic children involved in these miserable situations! Yes, just as there were abolitionists in America, there were champions of Child Labor Laws in Britain. But they were an impotent minority.

But whenever anyone sought to improve children’s working conditions, they encountered fierce opposition from the proprietors whose profits depended on exploiting them. They argued that any interference in the marketplace could cost Britain her manufacturing supremacy.

Even when regulations were eventually passed to improve working conditions, with only four inspectors to police the thousands of factories across the country they were seldom enforced. [Source]

Yes, the prime directive was keeping up a high “gross national product.”

A few laws were pushed past that issue, if there was enough pressure. But even then it doesn’t seem to have been just the “milk of human kindness” that brought change.

Many people had no idea that coal was excavated by young children. But it was the immorality rather than the cruelty of the mines that shocked them most.

An inspector described how, ‘The chain [used to pull the carts] passing high up between the legs of two girls, had worn large holes in their trousers. Any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can scarcely be imagined … No brothel can beat it.’

An Act was passed, prohibiting women and children under ten from working underground. Two years later, another Act was passed prohibiting the textile industry from employing children younger than nine.

But it was not until the mid-

So the ol’ Gross National Product wasn’t threatened until much later.

In 1880, the Compulsory Education Act helped reduce the numbers of child labourers, and subsequent laws raised their age and made working conditions safer. But it had come too late for the little white slaves on whose blood, sweat and toil our great railways, bridges and buildings of the Industrial Revolution were built. [ibid]

Too bad that the families of all those poor children couldn’t have immigrated to America! In 1849, around the time Britain was just getting around to investigating the Child Labor issue, a baby named Emma Lazarus was born in the US.

Emma grew up to be a noted poet. In 1883 she wrote her most famous work, “The New Colossus.” You may not remember that title, but you’ve heard some of the words of it…

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Yes, it is from the poem engraved on a plaque that adorns the base of the Statue of Liberty, which was erected in 1886.

And yes, here in the Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave, those miserable little British children of 1840 could have been guaranteed “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Free from the corrupt Old World Ways of class distinctions and exploitation of the poor by the wealthy. Because God gave a conviction of a manifest destiny to the founders of the country to spread from sea to shining sea, get rid of the prior inhabitants (so sorry about THEIR “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” but that’s progress for ya …), and make a place where little children could run free and pursue a beautiful future in any field they wanted.

And of course, the citizens and leaders of the USA throughout its history … until recently, anyway…fulfilled that destiny and nourished that glowing heritage!

Uh. Well. Not exactly. Britain began investigating child labor problems and passing laws attempting to curb its abuses in the 1840s. By the 1880s they had made a significant amount of progress. Here in the USA?

We didn’t get a child labor law in place until 1938. Throughout the US’s OWN Industrial Revolution times, into the early 1900s and beyond, hellish child labor conditions were common in the US, some of it quite comparable to that described above in the 1840s in Britain. Some serious attempts were made by a minority of concerned citizens to address the situation around the turn of the last century. But, ya see, the “financial” realities here at the time were exactly like those of Britain in their heyday of child labor. “Children were the ideal labourers: they were cheap (paid just 10-

And whaddaya know … in the Gay (18-

The silks and cottons the upper classes wore, the glass jugs and steel knives on their tables, the coal in their fireplaces, the food on their plates – [much] of it was produced by children working in pitiful conditions on their doorsteps. But to many of the monied classes, the poor were invisible: an inhuman sub-

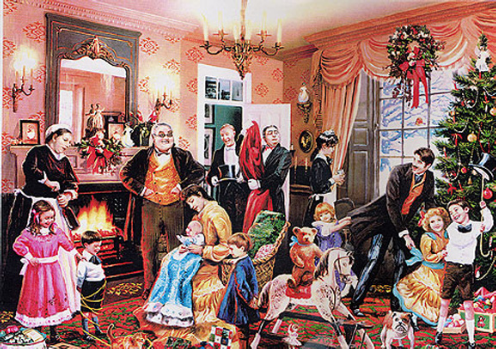

Children were precious in Gay Nineties America… if they were your own, or those of others of your own “class.”

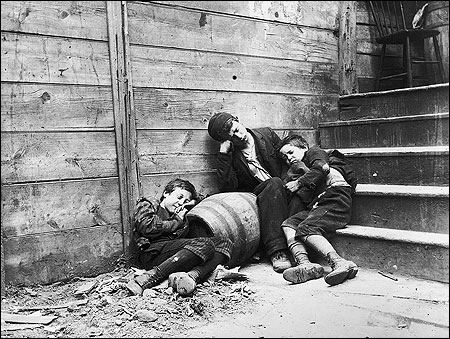

If they weren’t, to a large proportion of society they were just “urchins.” Such as these, from the famous 1890 photojournalism book by Jacob Riis about New York slums, How the Other Half Lives.

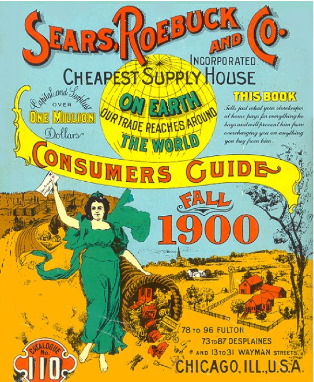

So what did it matter if the cheap prices you paid for gay Christmas clothes and jolly Christmas presents (like the Teddy and Rocking Horse above) from the 1900 Sears and Roebuck Catalog …

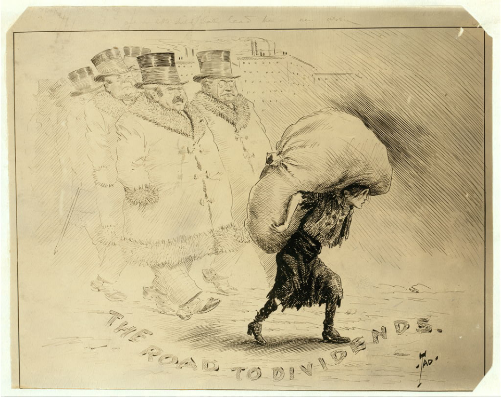

…were only possible, not because of the “blessings of God on our Manifest-

Yes. It didn’t matter. It was OK, because the urchins and their miserable families were assuring the US would … keep her manufacturing supremacy.

You might say that the situation gave new meaning to the biblical comment that “a little child shall lead them.”

If you are brave enough to explore this uncomfortable topic a little more deeply, you are invited to continue reading.