Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica

The Myth of Miss America

The Miss America Pageant began as a marketing idea. The Businessmen’s League of Atlantic City needed to develop a plan to keep tourists on the boardwalk past Labor Day. They organized a Fall Frolic and held it on September 25, 1920. There were many events that day, but the most popular was a parade of young women being pushed along the Boardwalk in rolling chairs. …

This event was such a success that a similar one was planned for the following year, and so on. At the same time, in an effort to increase circulation, newspapers on the East Coast had begun sponsoring beauty pageants judged on photograph submissions. The Businessmen’s League of Atlantic City got ear of this and decided to capitalize on this idea. They invited the winners of these local newspaper beauty contests to the next Fall Frolic to compete in an “Inter-

On September 8, 1921, one hundred thousand people came to the Boardwalk to watch the contestants, a turn out much more than the Businessmen’s League of Atlantic City had expected.

A panel of artists serving as judges named sixteen-

When Gorman returned in 1922 to defend her laurels, she was draped in the American flag and called “Miss America”. [Wiki]

Over 90 years later the “tradition” of crowning some young woman as Miss America in an annual pageant is continuing.

King Neptune crowned the first young lady with the splendiferous title, watched by perhaps 100,000 Americans in person.

By 1954, the pageant was seen by millions when it was first broadcast from Atlantic City on network TV. Bert Parks, popular TV host at the time of a game show called “Stop the Music,” became the host of the pageant in 1955 and remained through 1979.

Each year he would sing the Miss America theme song as the new MA was crowned, informing all the millions watching on TV …

There she is, Miss America

There she is, your ideal

The whole concept seemed to be that one perfect specimen of American Beauty would be offered up each year to the adoring American public as the epitome of American femininity. She was to be envied by all young American women, who should consider her qualities to be their chief aim in life. And adored by all other Americans as their view of Ideal Young Womanhood, a goal for their own young daughters to aspire to.

Well, not quite ALL young daughters.

From the beginning of the pageant in 1922, non-

Rule Number Seven was repealed in 1950, but …

…No African-

As late as 1940, all contestants were required to list, on their formal biological data sheet, how far back they could trace their ancestry. In the pageant’s continual crusade for respectability, ancestral connections to the Revolutionary War or perhaps the Mayflower would have been seen as a plus.

… Bess Myerson [above], Miss America 1945 and daughter of Russian-

“I said... the problem is that I’m Jewish, yes? And with that kind of name it’ll be quite obvious to everyone else that I’m Jewish. And you don’t want to have to deal with a Jewish Miss America. And that really was the bottom line. I said I can’t change my name. You have to understand. I cannot change my name. I live in a building with two hundred and fifty Jewish families. The Sholom Aleichem apartment houses. If I should win, I want everybody to know that I’m the daughter of Louie and Bella Myerson.” [Source]

And even though Myerson won the title, she still had to deal with prejudice. Many of the sponsors and events that had been associated with the Miss America pageant for years refused to include her in their usual Miss America promotions.

In addition to Myerson, others had pushed the boundaries of the pageant’s unwritten and written rules for inclusion. In 1941 a Native American, Mifauny Shunatona, represented Oklahoma at the pageant, though there would not be another Native American contestant for 30 years. Irma Nydia Vasquez from Puerto Rico, and Yun Tau Zane from Hawaii, the first Asian contestant, both broke the color bar in 1948.

Asian American comedian Margaret Cho recalls watching the pageant: “My father was very into it. And then, at one point when I was a little girl, I said oh I want to be one of those contestants. I want to grow up and do that, and he said no, oh no, you cannot do that, no. ...and I took it to mean that the beauty pageant was not open to all women. I mean my father thought that this whole pageant was fascinating and we would pick out the winners, but I was not allowed to even entertain the fantasy of becoming one of these women. And I thought well maybe I’m just not pretty enough. Maybe I’m just not white.”

The earliest Miss America contests were unabashedly “beauty contests.” They were intended to titillate the men in the audience with more skin than they usually got to see on young ladies. It was one thing to walk along the boardwalk in Atlantic City if you were a gentleman and try to casually and furtively sneak a peek at the young Flapper women and their constantly shrinking clothes in the early 1920s. It was quite another to be given societal permission to ogle for an extended period a group of young women being paraded especially for your inspection, like this Miss America contest group in 1925 (still officially referred to in this photo as the “Inter City Beauties—Atlantic City Pageant.)

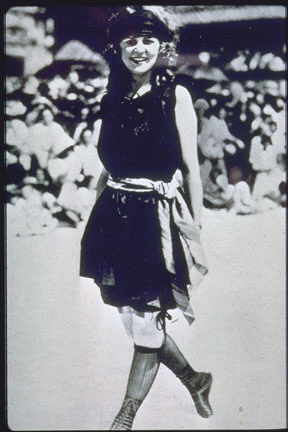

After all, just a decade earlier, most bathing beauties would have been garbed much like this…

So it is not surprising that the “beauty pageant” angle of the Miss America contest was its main drawing card. And although an “evening gown” competition segment was added long ago, I really can’t imagine most men of the heyday of the pageant on TV in the 1950s saying, “Wow…I gotta skip my bowling league tonight so I don’t miss the evening gown competition in the Miss America pageant.” From what I can tell, “All Eyes” have been only fixed on the bathing suit competition.

Oh, I’m sure lots of young women and their moms also were all excited about watching the talent competition section, with many vocal and piano pieces, mixed in with some tap-

And although publicity has surrounded the addition of “meaningful” parts of the competition, giving the girls a chance to show their speaking skills, and talk about their involvement in Important Causes, and express opinions about Issues of the Day, any notion that this trumps the bathing suit competition in audience attraction I believe is naïve. Especially since the addition of Bikini Competition.

The bottom line is this—I cannot imagine any place in the country where some girl with just average “looks” and a skinny, shapeless figure is playing a dynamite piano concerto and someone rushes up to her and insists, “You MUST enter the Miss State competition! You’ll be a sure winner to go on to the Miss America contest and win!”

There has been a Myth of Miss America that long reigned in in the US (although it has faded in recent years as interest in the contest has declined precipitously.) There was nothing wrong with a young lady having a pretty face and shapely figure. But those qualities were just something she was born with. No one could “aspire” to somehow “become like her.” For Bert Parks to have pointed every year at one out of the millions of young, pretty women in America and tell us in song “There she is, your ideal” was the height of nonsense.

It’s nice that most of the young women competing in that contest also had some sort of “artistic talent” like singing or tap dancing, and that at least the winners in recent decades have been pretty articulate. But to imply that one young woman whose only real credentials were that she made it through a string of beauty contests in her home town and state in order to arrive at the MA contest…is the “ideal” of All Americans, and a representative of The Best America Has to Offer the World of femininity is just plain silly.

I would hope many Americans intuitively understand this. But I fear that, particularly in years past, vast numbers of young women did not understand this. Like Margaret Cho, they indeed thought that the young woman beaming under her crown on TV was worthy of their awe, and had aspirations to become just like her. (Or deep depression and feelings of worthlessness at the reality they didn’t have a snowball’s chance in hell…)

They believed the Myth.

And Myths—when accepted as reality—can be powerful.

Most adult Americans studied the Myths and Mythology of the ancient Greeks and Romans and Vikings back in high school.

We all knew that they were myths—invented stories, created by the Ancients that purported, in part, to explain “how things got to be the way they were.” We easily spot more modern mythology in the cultures of other people. We are irritated when other countries, such as Russia, “adjust” their own histories to make themselves appear more noble in their actions than they really have been. We bristle when they glorify men of the past in their own countries whom we consider to have been evil. We protest when they recount historical events in ways that change the historical narrative totally from the way we perceive it to have been.

Americans don’t tell myths as if they are the truth.

Or do we?

When I was a small child, my parents indoctrinated me in the myth of Santa Claus. I can still remember being four years old, struggling to fall asleep on Christmas Eve when I heard a “clattering” outside in the snow. I stood up on my bed and peeked out my window, and saw a shadowy figure lurking about the house next door. It never occurred to me to worry about it being a burglar. I was SURE it was Santa Himself, and thus I flopped back down in bed and covered up my head, not wanting him to see me lest he’d be angry I wasn’t asleep like I should be. For, after all, “He sees you when you’re sleeping, he knows when you’re awake, he knows if you’ve been bad or good, so be good for goodness’ sake!”

That same year, my mother fed my acceptance of the Santa Myth by sending a letter with my name in it to the local radio station’s Santa. And he read it right out loud on the Santa radio program just days before Christmas! Yes, I knew that he knew me by name!

But something happened when I was age seven that shook my world. It was just before Christmas. I was rummaging in the kitchen cupboards, up in a higher one than I usually looked in, and found several sacks of special candy. I kept quiet about my find. But a few days later, on Christmas morning, I found my Christmas stocking filled with that same candy. I was horrified. It dawned on me that the stuff in my stocking, and the wrapped gifts every year that said “From Santa” on them, were actually from my parents.

Even into her eighties, my mother remembered my reaction to the situation—I had indignantly asked how she and Dad could have lied to me all those years, and vowed that when I had children of my own I would never try to trick them into believing such a myth as if it were the truth.

No, I have never liked, even as a young child, being misled by myths, even well-

And, other than when they indulged in the childhood myths such as Santa, I had long assumed that most Americans were equally addicted to truth. When I studied history in grade school, high school, and college, I carefully separated in my mind American History, all based on “facts,” and the history portrayed by the records of the ancient Greeks and Romans and other civilizations that thrived on interspersing fact with mythology, traditions, and superstitions in an indistinguishable mish-

This is not to say that I didn’t realize that there were “American Myths” or fables or legends…Paul Bunyan and his big blue ox Babe, Pecos Bill, John Henry. But they were clearly just that, fables, legends, or folklore.

Or fakelore:

Fakelore or pseudo-

The term fakelore was coined in 1950 by American folklorist Richard M. Dorson. Dorson’s examples included the fictional cowboy Pecos Bill, who was presented as a folk hero of the American West but was actually invented by the writer Edward J. O’Reilly in 1923. Dorson also regarded Paul Bunyan as fakelore. Although Bunyan originated as a character in traditional tales told by loggers in the Great Lakes region of North America, James Stevens, an ad writer working for the Red River Lumber Company, invented many of the stories about him that are known today. According to Dorson, advertisers and popularizers turned Bunyan into a “pseudo folk hero of twentieth-

Yes, as a child of the fifties who watched Wonderful World of Disney on TV, I was well familiar with both fakelore and folklore.

And it’s not to say that I didn’t realize that certain “tidbits of history” like the story of George Washington and the cherry tree had been fabricated early on in our history to spruce up the biographies of our early American Heroes. Embellishments like that don’t really change the central “facts” of our history.

But in recent years, I have discovered to my chagrin that I have been painfully unaware that I have accepted huge swaths of mythology in American history as fact. Not minor tidbits like the cherry tree—major concepts that have affected millions in the past as well as continuing to affect our nation now. Looking back, I have a hard time understanding how I could have “missed” all of this. I am not speaking of things “hidden in a corner,” but information openly available, with careful documentation, from standard reference sources.

I do somewhat understand now—the reality is that history is a huge collection of billions of factors and factoids and incidents, and any view of any corner of it must come to us through a filter of some kind. Someone has to choose which of those billions of incidents and factors to put under the microscope and take a closer look at. And since much of what most of us know about “facts” of history was funneled into our heads during our school years, whatever the authors of our textbooks focused on is what we now “know.”

Or think we know.

In recent of years, I have discovered that the filter of my own school textbooks (as well as other social filters like movies), was deeply flawed, and I was left with a distorted view of some of the most significant factors in US History. As the old Paul Harvey radio program put it, there is a “Rest of the Story” to many historical eras and events of which I have been woefully ignorant. In many cases I have accepted a mythology instead of documented facts.

This is my country, land of my birth. I want to know the truth about it: the good, the bad, the ugly, the beautiful, the noble—and the ignoble. I don’t want to believe a candy-

I believe it is time to dispel many of the mythperceptions about our history so we can clearly see our way forward.

I invite you to join me on the journey.