Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

Uncle Sam’s Kids, Part 4

The Declaration of Dependence

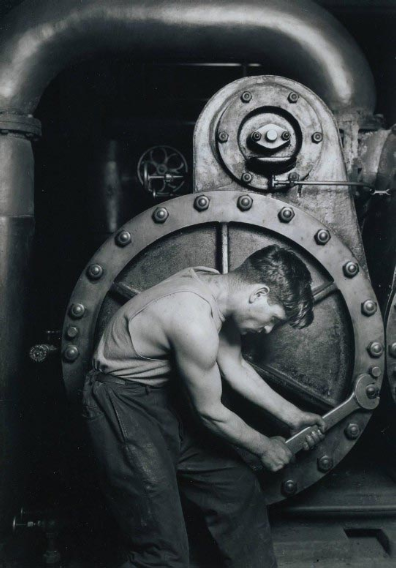

Famous documentary photographer Lewis Hine certainly wasn’t against hard work!

After documenting the horrors of child labor for so many years [the decade from 1908 to 1918], Hine wanted to focus on the dignity of labor, on its skills and satisfactions. His major project during the 1920s was an ambitious, celebratory series of “Work Portraits”—photographs of working people and craftsmen, the men and women who turned the massive wheels of industry. His goal was to highlight the importance of human labor in the new age of the machine.

“Cities do not build themselves, machines cannot make machines, unless back of them all are the brains and toil of men,” he emphasized. In his Work Portraits, Hine viewed the American worker as a heroic figure who could take great pride in his or her craft. [Kids at Work, Russell Freedman]

Hine made some amazing portraits of such workers, which certainly dignify the “toil of men.”

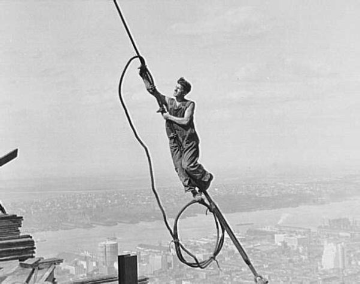

The most amazing of all were his candid photos of men working on building the Empire State Building in 1930.

Worker pretends to be “touching” the top of

the Chrysler Building, far below.

Sky High Siesta!

But it’s pretty obvious from the muscles on that fellow working his wrench in the first picture that these men were FIT for the work they were doing. Fit by age and strength, skill and experience, physical growth and mental and bodily maturity.

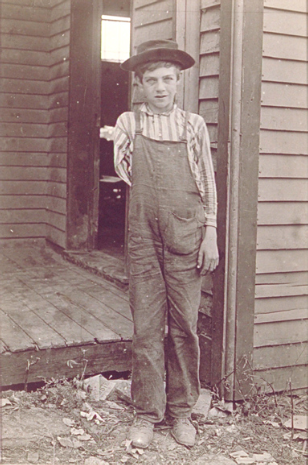

Not so the earlier workers Hine made portraits of…

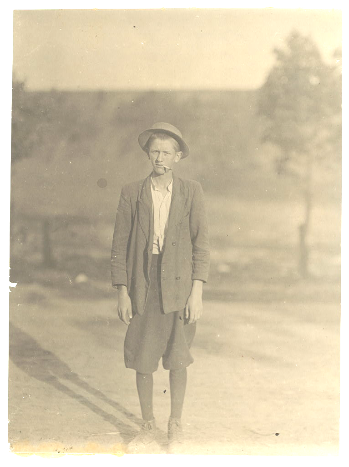

(1912, Picture Title from Hine: Human Junk.)

A product of the mill. “Ben workin fer 10 years. Began when I was six years old

for 5 cents a day. Lately I was workin $1.25 a day but got to spittin blood

and had to quit.” He was truely [sic] “scrapped” and of little use to himself or the world. Roy Hammett, Spartanberg [sic], S.C. [Hine]

Please note that Hine’s use of the term “human junk” wasn’t intended to be a value judgment on that young man’s worth as a human being. It was an ironic statement of what he had become to “the system” at the tender age of 16, when young men in the “higher classes” in the US were just getting ready to set out to make their way in the world after getting a good education. This young man had no future … he was just a piece of scrap to be tossed on the heap when he could no longer fit as a cog in the machine.

Children, many of them pre-

He may have made it to adulthood all in one piece, but many of his co-

Insurance? Liability? Compensation? HAH.

In many cases, young people like this were lucky if a company doctor bound up a work-

The businesses employing these young people were getting all the benefit of slave labor, and unlike pre-

As his photographs attracted more attention, factory owners and sweatshop employers began to refuse to grant Hine access to their worksites. In response, he began hide his camera. He gained entry by posing as a fire inspector or an agent of a licensing board. Hine also began giving public lectures on child labor. At one such lecture, when confronted by an audience member who complained of being tired of seeing the photographs of pathetic children, Hine responded “Perhaps you are weary of child labor pictures. Well, so are the rest of us, but we propose to make you and the whole country so sick and tired of the whole business that when the time for action comes, child labor pictures will be records of the past.” [Source]

Unfortunately, his goal was not reached. His photographs flooded the media in the United States, and they did indeed spur some action by some whose hearts and minds were touched by what he showed. But that action bore no lasting fruit for another 25 years. The abuses of child labor continued. Such as those shown in the photos below.

Oyster shuckers working in a canning factory.

All but the very smallest babies work.

Began work at 3:30 a.m. and expected to work until 5 p.m. [13.5 hours]

The little girl in the center was working.

Her mother said she is “a real help to me.” Dunbar, Louisiana. [Hine]

Cutting fish in a sardine cannery. Large sharp knives are used with a cutting

and sometimes chopping motion. The slippery floors and benches

and careless bumping into each other increase the liability of accidents.

“The salt water gits into the cuts and they ache,” said one boy. Eastport, Maine. [Hine]

Fish cutters at a canning company in Maine. Ages range from 7 to 12.

They live near the factory. The 7-

has a badly cut finger but helps his brother regularly.

Behind him is his brother George, age 11,

who cut his finger half off while working.

Ralph, on the left, displays his knife and also a badly cut finger.

They and many youngsters said they were always cutting themselves.

George earns a dollar some days usually 75 cents.

Some of the others say they earn a dollar when they work all day.

At times they start at 7 a.m. and work all day until midnight.

[17 hour shift … for a dollar or less]

Manuel the young shrimp picker, age 5,

and a mountain of child labor oyster shells behind him.

He worked last year. Understands not a word of English. Biloxi, Mississippi. [Hine]

Manuel is five years old but big for his age. When the whistle blows at 3 o’clock in the morning, he pulls on his clothes and hurries to the shrimp and oyster cannery where he spends the day peeling the shells of iced shrimp. He has been working as a shrimp-

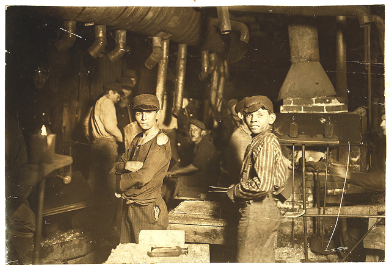

Boy in glass factory, Virginia, 1911

Boys in a glass factory in Indiana after midnight, 1908

Glass making was another industry that employed thousands of boys in tough and dangerous jobs. Most of these youngsters worked as blowers’ assistants in glassworks furnace rooms. The intense heat and glaring light of the open furnaces, where the glass was kept in a molten state, could cause eye trouble, lung ailments, heat exhaustion, and a long list of other medical problems.

The temperature of molten glass is 3,133 degrees Fahrenheit. The temperature in the glass factories ranged between 100 and 130 degrees. Fumes and dust hung in the air. Broken glass littered the floors. It wasn’t surprising that cuts and burns were the most common injuries.

Workers were paid by the piece, so they had to keep moving fast for hours at a time without a break. A typical glassblower’s assistant made about sixty-

Since the furnaces were kept burning continuously, glass factories operated around the clock. Many of the boys were required to work at night. Often, they faced a transportation problem. The night shift started at 5:00 P.M. and ended at 3:00 A.M., when there was no streetcar service. A boy had the choice of a nap on the factory floor until five or six o’clock, when the cars started running, or a long walk home in the dark. In winter, this meant a sudden change from the hot air inside the factory to the frigid air outside.

Because of these unhealthy and hazardous work conditions, employees in the glass-

Factory owners claimed that they couldn’t operate without the labor of young boys, that workers over sixteen were too slow and clumsy to perform the boys’ work. And yet most adult glassworks employees refused to let their own kids follow them into the factories. As one longtime worker put it: “I would rather send my boys straight to hell than send them by way of the glass house.” [Freedman]

Yes, most child labor jobs held all kinds of threats to the safety and health of the children involved. They could contract lung diseases and other life-

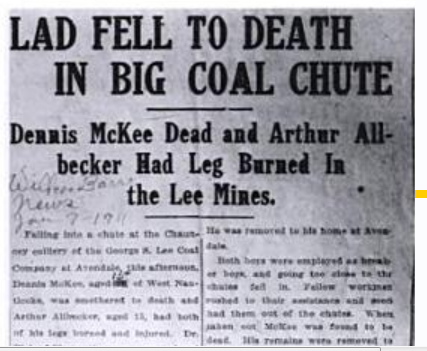

Lunchtime among the Breaker Boys

Many of the breaker boys suffered from chronic coughs. “There are twenty boys in that breaker,” one of the foremen said, “and I bet you could shovel fifty pounds of coal dust out of their system.” … Their faces black with soot, they sat in rows on wooden boards placed over coal chutes. As coal came pouring through the chutes, the boys bent over, reached down, and picked out pieces of slate and stone that could not burn. They had to watch carefully, since coal and slate look so much alike. If a boy reached too far and slipped into the coal that was constantly flowing beneath him, he could be mangled or killed. “While I was there, two breaker boys fell or were carried into the coal chute, where they were smothered to death,” Hine reported from a Pennsylvania mine.”

This was evidently not all that uncommon.

Wilkesbarre, PA, 1911

Again … insurance? Liability? Restitution? Hah.

A newspaper reporter who saw an exhibit of Hine’s photos at a conference in Birmingham, Alabama, was stunned by the power of the images. He wrote:

“There has been no more convincing proof of the absolute necessity of child labor laws … than these pictures showing the suffering, the degradation, the immoral influence, the utter lack of anything that is wholesome in the lives of these poor little wage earners. They speak more eloquently than any [written] work — and depict a state of affairs which is terrible in its reality — terrible to encounter, terrible to admit that such things exist in civilized communities.” [Source]

Hine’s photos were meant to shock and anger those who saw them. They were intended to mobilize public opinion, and that is exactly what they did. The photos became a powerful weapon in the crusade against child labor.” [Freedman]

Yes, Hine’s photos shocked and angered some.

“There is work that profits children, and there is work that brings profit only to employers. The object of employing children is not to train them, but to get high profits from their work.”– Lewis Hine, 1908

…child laborers barely experienced their youth. Going to school to prepare for a better future was an opportunity these underage workers rarely enjoyed. As children worked in industrial settings, they began to develop serious health problems. Many child laborers were underweight. Some suffered from stunted growth and curvature of the spine. They developed diseases related to their work environment, such as tuberculosis and bronchitis for those who worked in coal mines or cotton mills. They faced high accident rates due to physical and mental fatigue caused by hard work and long hours.

By the early 1900s many Americans were calling child labor “child slavery” and were demanding an end to it. They argued that long hours of work deprived children of the opportunity of an education to prepare themselves for a better future. Instead, child labor condemned them to a future of illiteracy, poverty, and continuing misery. [Source]

Alexander J. McKelway, assistant secretary in the National Child Labor Council wrote a publicity piece used in NCLC literature from about 1908 on that expresses these concerns succinctly:

Declaration of Dependence

by the Children of America

in Mines and Factories and Workshops Assembled

Whereas, We, Children of America, are declared to have been born free and equal, and

Whereas, We are yet in bondage in this land of the free; are forced to toil the long day or the long night, with no control over the conditions of labor, as to health or safety or hours or wages, and with no right to the rewards of our service, therefor be it

Resolved, I — That childhood is endowed with certain inherent and inalienable rights, among which are freedom from toil for daily bread; the right to play and to dream; the right to the normal sleep of the night season; the right to an education, that we may have equality of opportunity for developing all that there is in us of mind and heart.

Resolved, II — That we declare ourselves to be helpless and dependent; that we are and of right ought to be dependent, and that we hereby present the appeal of our helplessness that we may be protected in the enjoyment of the rights of childhood.

Resolved, III — That we demand the restoration of our rights by the abolition of child labor in America.

But the children couldn’t “fight” for themselves as did the American Revolutionaries after they made their Declaration of INdependence. And thus it was another 25 years before any meaningful reforms came.

Congress passed laws [regulating child labor] in 1916 and 1918, but the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional because they infringed on states’ rights and “denied children the freedom to contract work.” In 1924, Congress passed a constitutional amendment authorizing a national child-

Child labor began to disappear only during the Great Depression of the 1930s, in no small part because adults found themselves competing for the lowest-

As you see, even 25 years after the “Children’s Declaration of Dependence,” the reforms didn’t seem to come from the open recognition by political leaders, industrial leaders, and the masses of common citizens on the street that child labor had been an abomination in its own right, destroying young lives. No, it was more a “political choice” related to demands of adult labor to not have to compete with the kind of wages that could be paid children. Prior to that, there were so many adults willing to actively “lobby” AGAINST any control of child labor conditions that even a constitutional amendment, approved by the US congress, was effectively thwarted by the states! Yes, it wasn’t just a few men “at the top” of our government who allowed child labor abuses to continue for so long in this country. It was a large number of citizens.

In other words, in the end, it wasn’t so much that the populace in general was appalled to learn that so many kids were worked to an early death. It was that they “took the jobs” of adult men. So the heartless capitalists who used poverty-

This is not to say that all adult unskilled laborers who competed with children for jobs before 1938 had no concern for the abuses of child labor, of course. No doubt some had great compassion for young children and supported child labor laws because of it. But the historical record shows that this was never enough to actually get anything DONE about the child labor problem until the Great Depression of the 1930s made it a flash-

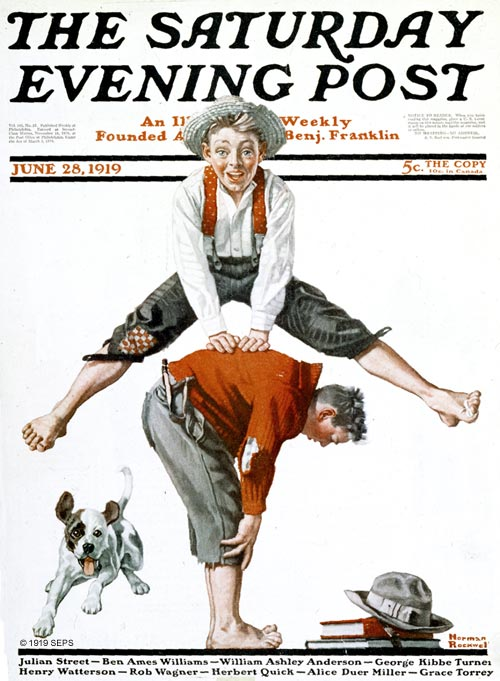

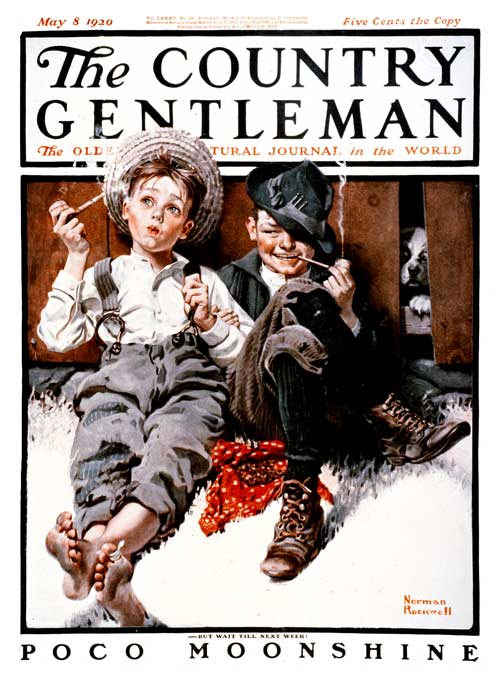

I can’t speak for anyone else, but I’ll bet my personal experience is quite common. Over the years I developed my view of what life was probably typically like for the children of the US around the turn of the last century–say 1890 to the 1920s–primarily from sources such as the Disneyesque paintings of Norman Rockwell. You could picture the kids in Rockwell’s paintings living on streets branching off from Walt’s Mythical Main Street. Or out in the country near towns that had a similar iconic Main Street. If you’ve ever admired Rockwell’s folksy paintings (I always have … there are five books of collections of them in my personal library) you may even recognize these sample kids.

Actually, I don’t doubt that many children who looked pretty much like these kids, and who lived carefree lives much like these kids, did live in many towns all across America. But note that these covers are from the same general time period as that of the photos of Lewis Hine.

I’m not suggesting that Rockwell should have painted the emaciated, malnourished, beaten down kids in the coal mines or cotton mills! Rockwell was a commercial artist, and that sure wouldn’t have helped sell issues of The Saturday Evening Post or The Country Gentleman or The Literary Digest!

But when the faces of the whimsical, free-

And thus it has left most of us believing a very distorted “history” of our country.

Why care? How might this distortion affect the way we view the present and the future, today?