Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

Uncle Sam’s Kids, Part 2

Lewis Hines’ Kids

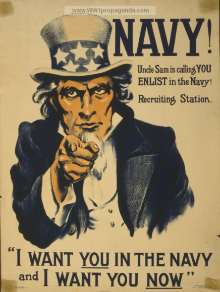

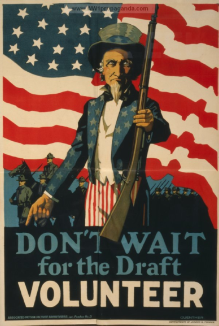

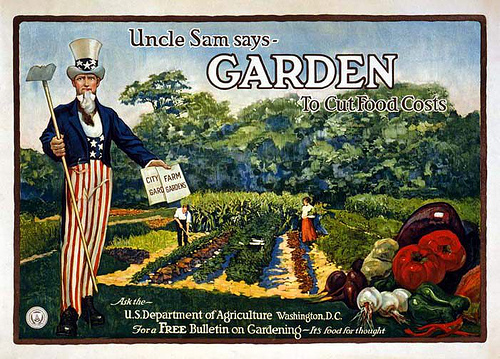

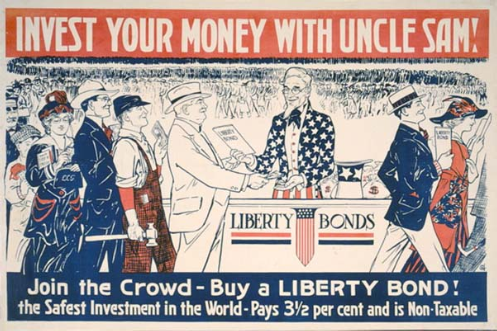

What with the commercial world filled with iconic characters galore in recent decades, from Ronald McDonald to Spongebob Squarepants, ya don’t see ol’ Uncle Sam much anymore. But back 100 years and more ago, he was a real hot commodity! He showed up everywhere, doing his job of reminding adults and kids alike that Our Country was the source of bountiful blessings—and also doing his job of selling lots o’ stuff…and ideas. Of course almost everyone has seen his hard-

And he encouraged patriotic citizens to help in the War effort by planting Victory Gardens…

…and buying Liberty Bonds.

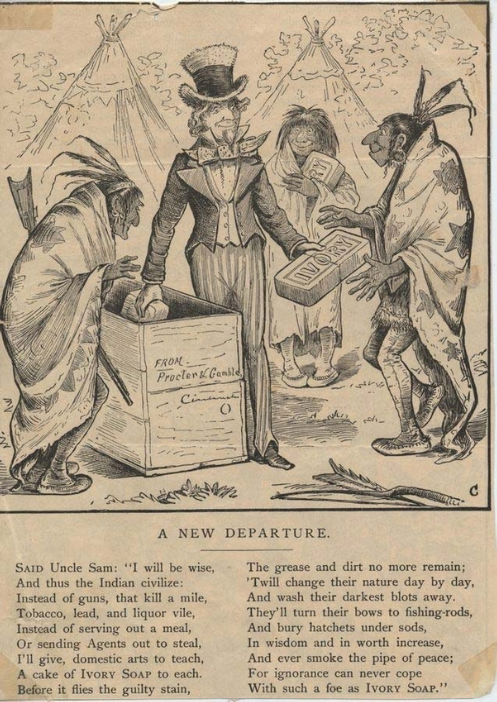

But you may not know he also sold soap…

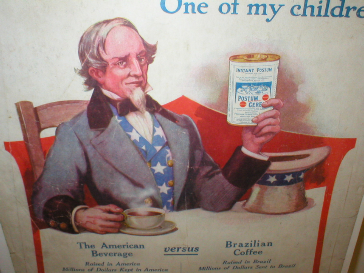

… and Postum…

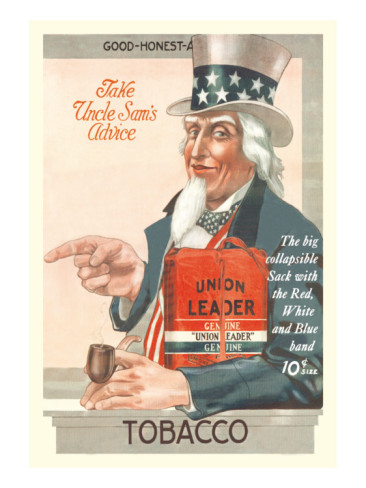

…and even tobacco…

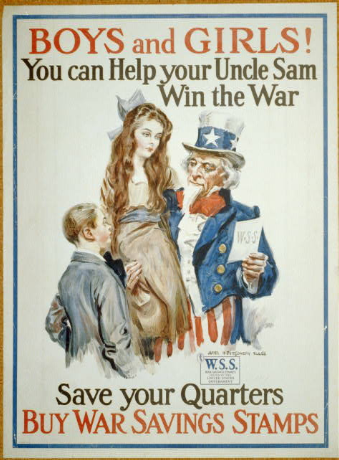

… and a whole lot more. As you can imagine, he was particularly a popular figure to children. They swarmed around him as he encouraged them (especially those pretty young girls!) to buy war bonds.

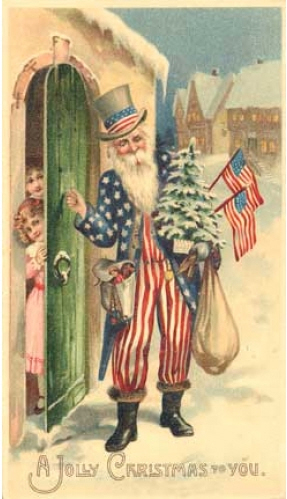

And you can’t blame them for even wondering if maybe the true Gift Bringer on Christmas wasn’t really Santa—maybe St. Nick was an imposter trying to get the glory due the beneficent Uncle Sam!

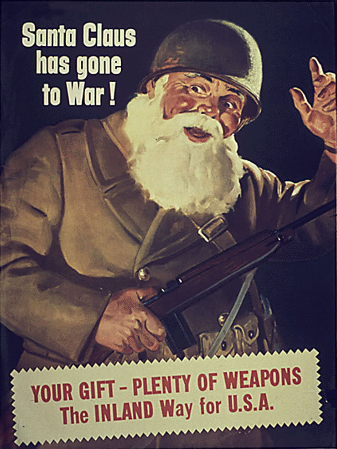

Or maybe Uncle Sam was just filling in for Santa while Santa was busy Over There in the Great War?

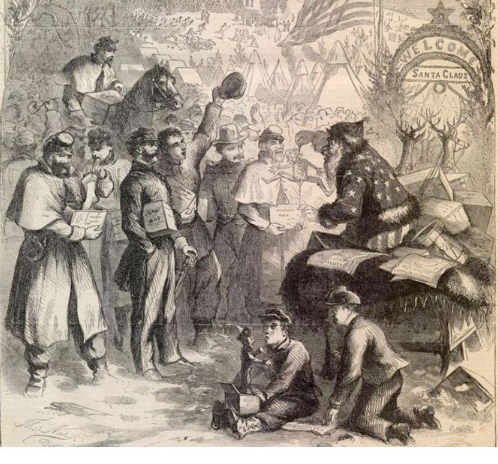

Nah–that poster was from WW2. Santa was probably a Conscientious Objector in WW1. Although going back a half century before that, he does seem to have been the Bob Hope of the Civil War, as seen in this pic by Thomas Nast for the cover of Harper’s Weekly in 1863. (He was obviously a Yankee…)

But let’s get back to Uncle Sam. Sam was certainly very busy in the 1800s and early 1900s. You might say Sam was every kid’s favorite uncle. And why not? They lived in the bestest, most prosperous, most bountiful land on earth, and owed it all to him. So what were Uncle Sam’s kids like back in his heyday?

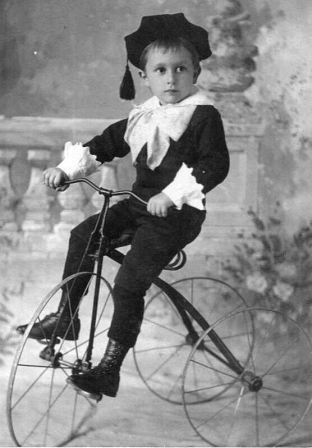

You’ve no doubt seen pics of the dolled-

Yes, long curly locks, frilly lace, and swirling skirts were all the fashion. Even for girls— no, that’s not a little girl above, that’s Franklin D Roosevelt at about age 3, in about 1885. At the time, little boys up to the age of five or so still wore skirts (some historians claim that was because of the difficulty younger boys had in dealing with clothing fasteners of the time when attending to toileting matters.) Unfortunately for him, FDR was born just a very tiny bit too early for the change in young boys’ fashion that was spawned that very year by the description of the young hero of a children’s novel written in England by Frances Hodgson Burnett (also author of The Secret Garden.) Finally young boys could wear pants instead of skirts. Although the rest of the get-

“What the Earl saw was a graceful, childish figure in a black velvet suit, with a lace collar, and with lovelocks waving about the handsome, manly little face, whose eyes met his with a look of innocent good-

The book had detailed illustrations by Reginald Birch that made it easy for seamstresses in England and America to mimic the look.

The Fauntleroy suit appeared in Europe as well, but nowhere was it as popular as America. The classic Fauntleroy suit was a velvet cut-

Yes, for a while it seemed like Little Lords were everywhere!

But the Young Ladies weren’t left out—their fashionable finery was just as elegant.

And of course the young lads didn’t always wear their Fauntleroy suits, as you can see by the winter Sailor Suit in the pic above. Their clothes closets would have had a variety of manly fashionable styles to choose from too, depending on their plans for the day.

Well, some of the lads would have had this variety. Not all of them. Others wouldn’t have needed it, because their plans were the same for EVERY day.

For ol’ Uncle Sam had some kids in his family before, during, and after the Gilded Age that never showed up on the patriotic posters, the sentimental Christmas cards, or the cheery ads for breakfast drinks. LOTS of kids. They were out of sight, out of mind most of the time to the rest of Sam’s great American Family.

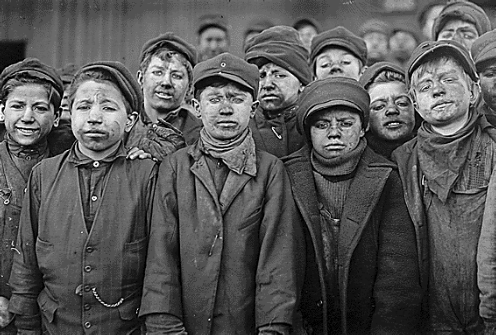

But there were millions of them. They were the child laborers (such as the young coal mine “breaker boys” shown above) whose back-

The Way Things Were Supposed to Be

Back when I was a young person myself, I came across an interesting book belonging to my granny. She had obviously inherited it from her mother or grandma—Granny was born in 1903, but this book was published in 1890. I still have the book, as a matter of fact. It’s hard to read the title on the aged cover now, but I found a pic of the exact same book on E-

I’ll bet you that my great grandmother bought this impressive volume from a traveling door-

The 523 page Encyclopedia of Household Information was designed to take a newly-

Children have rights which parents are bound to respect. They have the right to love, to be fed and clothed, and educated; to be supplied with interesting and instructive papers and books, and to be furnished with means of recreation and amusement in other ways. All this may be done in reason. The humblest may have their innocent enjoyments and pastimes, as well as those who are in the best worldly circumstances. (P.186)

By “the humblest,” I assume the author was speaking of children of “poor” families. But it was a very naïve view that ignored what was a reality for a large number of such children. For there were millions of exhausted children—some as young as five or six—in the US at that time for whom ANY free time to indulge in “pastimes” was unavailable. They were either working or sleeping—or traveling to or from work—for almost the entire 24 hours of every day. “Innocent enjoyments”? Not for those working 12 to 15 hour shifts in the mines or mills or factories.

Please note that we aren’t talking of the early 1800s here. We are talking clear into the 20th century in the land that promised “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” No pursuing of happiness was available to these children. And no liberty. Life? I guess that depends on what you consider “having a life.” A future? Most of these children had nothing to look forward to when they got PAST childhood either.

Trapped in the tenement slums of the northern big cities, or the impoverished “company towns” connected with the coal mines in Pennsylvania or Virginia or the cotton mills of North and South Carolina or Georgia, with little or no education, most were doomed from the start of their often short lives to a futureless future.

We’ll get personal and meet a few individuals and groups of them. This is made possible by the work of Lewis Hine.

Born in 1874, Hine was a sociologist, teacher, and eventually an investigative reporter/photographer.

You may have seen some of his work, particularly the amazing pictures he took in 1930 chronicling the work of the brave men who built the Empire State Building.

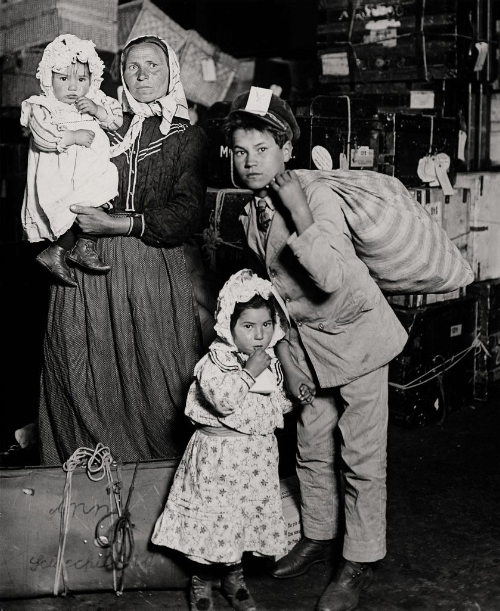

In the early 1900s, he and his students photographed immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, such as this Italian family.

Between 1904 and 1909, Hine took over 200 plates (photographs), and eventually came to the realization that documentary photography could be employed as a tool for social change and reform. … In 1908, he became the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), leaving his teaching position. Over the next decade, Hine documented child labor in American industry to aid the NCLC’s lobbying efforts to end the practice. [Wiki: Hine]

He had many other photography jobs over the coming years, but late in his career, people lost interest in him, he died in poverty, and no one even wanted his amazing collection of photographic negatives and prints after he passed away. His son finally got the George Eastman House, a photography museum, to accept them. A resurgence of interest in his work in recent decades has made his name famous, and his works are now distributed among several prestigious institutions.

The Library of Congress holds more than five thousand Hine photographs, including examples of his child labor and Red Cross photographs, his work portraits, and his WPA and TVA images. Other large institutional collections include nearly ten thousand of Hine’s photographs and negatives held at the George Eastman House and almost five thousand NCLC photographs at the Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. [ibid]

Hine took careful notes when he made his photographs of people, and I have included some of his own captions for the photographs below of child laborers in the US during the first and second decades of the 20th century. His comments are followed by [Hine]. Other clarifying material may be from various websites. See the link to those in brackets after the entry.

By the way, although there were no national child labor laws in the US during the time Hine was taking these photos, there were some state laws that it was obvious to him were being flouted by the employers of these young children—because enforcement of most such laws was close to non-

Manning, a Massachusetts historian researching what happened to some of the children in the pictures, explained that Hine got into mills and factories by flattering the managers, offering to take their pictures.

“He’d go in as an industrial photographer,” Manning said. “He said, ‘I want to take a picture of that machine.’ He’d set up his camera, then ask a supervisor to bring a child worker into the picture “‘so we can tell how big it is.’“

Hine would then ask the child worker for his or her name, write it down, “and get the heck out.” [Lewiston, Maine, Sun Journal article on Hine]

Minor Coal Miners

No Rest for the Weary Children in the Coal Mines

For early twentieth-

“View of the Ewen Breaker of the Pennsylvania Coal Co. The dust was so dense at times as to obscure the view. This dust penetrated the utmost recesses of the boys’ lungs. A kind of slave-

The coal was crushed, washed, and sorted according to size at the breaker. The coal tumbled down a chute and moved along a moving belt. Boys, some as young as eight, worked in the picking room. They worked hunched over 10 to 11 hours a day, six days a week, sorting rock, slate and other refuse from the coal with their bare hands. If the boy did not pay attention, he might lose fingers in the machinery. [Source]

Spargo:

Work in the coal breakers is exceedingly hard and dangerous. Crouched over the chutes, the boys sit hour after hour, picking out the pieces of slate and other refuse from the coal as it rushes past to the washers. From the cramped position they have to assume, most of them become more or less deformed and bent-

The coal is hard, and accidents to the hands, such as cut, broken, or crushed fingers, are common among the boys. Sometimes there is a worse accident: a terrified shriek is heard, and a boy is mangled and torn in the machinery, or disappears in the chute to be picked out later smothered and dead. Clouds of dust fill the breakers and are inhaled by the boys, laying the foundations for asthma and miners’ consumption.

I once stood in a breaker for half an hour and tried to do the work a twelve-

I could not do that work and live, but there were boys of ten and twelve years of age doing it for fifty and sixty cents a day. Some of them had never been inside of a school; few of them could read a child’s primer. True, some of them attended the night schools, but after working ten hours in the breaker the educational results from attending school were practically nil. “We goes fer a good time, an’ we keeps de guys wot’s dere hoppin’ all de time,” said little Owen Jones, whose work I had been trying to do. . . .

As I stood in that breaker I thought of the reply of the small boy to Robert Owen. Visiting an English coal mine one day, Owen asked a twelve-

From the breakers the boys graduate to the mine depths, where they become door tenders, switch boys, or mule drivers. Here, far below the surface, work is still more dangerous. At fourteen or fifteen the boys assume the same risks as the men, and are surrounded by the same perils. Nor is it in Pennsylvania only that these conditions exist. In the bituminous mines of West Virginia, boys of nine or ten are frequently employed.

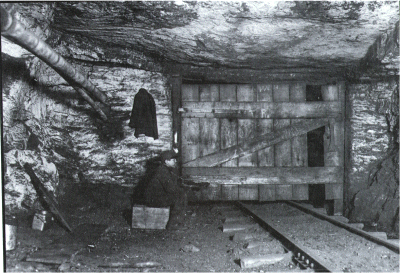

The nipper [also called a trap boy] was the door keeper. He was the youngest of the boys working underground, usually eleven to thirteen years old. His job was to open the heavy door when he heard a coal car approaching, then quickly close the door after the load passed through. The nipper sat long hours by himself in the dark with only his carbide cap lamp for light. He was often bored and sometimes whittled long pieces of wood into sprags or trapped the rats to pass the time.

When the nipper heard an approaching car, he opened the door to let the mule and the driver pass through with their load of coal. It was very important that the nipper did not fall asleep and allow the coal car to crash through the door. The door was vital to the mine’s ventilation system. [Source]

Spargo:

I met one little fellow ten years old in Mt. Carbon, W. Va., last year, who was employed as a “trap boy.” Think of what it means to be a trap boy at ten years of age. It means to sit alone in a dark mine passage hour after hour, with no human soul near; to see no living creature except the mules as they pass with their loads, or a rat or two seeking to share one’s meal; to stand in water or mud that covers the ankles, chilled to the marrow by the cold draughts that rush in when you open the trap door for the mules to pass through; to work for fourteen hours—waiting—opening and shutting a door—then waiting again for sixty cents; to reach the surface when all is wrapped in the mantle of night, and to fall to the earth exhausted and have to be carried away to the nearest “shack” to be revived before it is possible to walk to the farther shack called “home.”

Boys twelve years of age may be legally employed in the mines of West Virginia, by day or by night, and for as many hours as the employers care to make them toil or their bodies will stand the strain. Where the disregard of child life is such that this may be done openly and with legal sanction, it is easy to believe what miners have again and again told me—that there are hundreds of little boys of nine and ten years of age employed in the coal mines of this state. [John Spargo, The Bitter Cry of Children (New York: Macmillan, 1906), 163–165.]

At the end of the day…

“At the close of day. Waiting for the cage to go up. The cage is entirely open on two sides and not very well protected on the other two, and is usually crowded like this. The small boy in front is Jo Puma. South Pittston, Pennsylvania.” [Hine]

Cotton Mills

Then there were the cotton mills, mostly in the South.

“Some boys and girls were so small they had to climb up on to the spinning frame to mend broken threads and to put back the empty bobbins. Bibb Mill No. 1. Macon, Georgia.” [Hine]

Accidents and injury were a constant threat in the cotton mills. Employees worked amidst heavy, fast-

Accidents were unfortunately common among child workers, who were inexperienced and could at times be easily distracted. James Pharis began working at Spray Cotton Mill near Eden, NC as a child of eight years old. He permanently injured his hand at age nine while riding an elevator system rigged up with pulleys. “We’d ride the elevator rope up to the pulley and slide back down,” he explained. “I was riding one day and was looking round over the spinning room and my hand got caught under the wheel….that thing was mashed into jelly. All of it was just smashed all to pieces.” [University of North Carolina]

“Children on the night shift going to work at 6 p.m. on a cold, dark December day. They do not come out again until 6 a.m. [12 hour shift] When they went home the next morning they were all drenched by a heavy, cold rain and had few or no wraps. Two of the smaller girls with three other sisters work on the night shift and support a big, lazy father who complains he is not well enough to work. He loafs around the country store. The oldest three of these sisters have been in the mill for 7 years, and the two youngest for two years. The latter earns 84 cents a night. Whitnel, North Carolina.” [Hine]

During the late 19th and early 20th century, the few laws prohibiting child labor were moderate and rarely enforced. In North Carolina, the age limit was 13 for employment in factories such as mills, and children under 18 were allowed to work up to a shocking 66 hours per week! Mill owners had to “knowingly and willfully” break these laws before they could be convicted. Even more lenient laws were in place in South Carolina, where the age limit for factory workers was 12 years old. However, orphans and children with “dependent” parents (those too sick to work) could work at any age and any amount of hours. These laws were rarely, if ever, enforced. Former child workers remember scrambling to hide in closets on the few occasions when factory inspectors would visit to check on working conditions in the mill. [ibid]

“LINCOLNTON, N. C. Six years old. Stays all day in the mill where his mother and sister work. Is beginning to “help” a little and will probably soon be regularly at work, though his name may not appear on the payroll.” [Hine]

The system of “helpers” was another way mill owners got around child labor laws. Very small children as young as 6 or 7 years old would visit the mill to bring meals to their parents or older siblings during the work day or simply to play amidst the machinery. These young “helpers” would begin to learn the jobs that older workers performed and try their hand at various tasks. The presence of tiny children in the mill could be explained to inspectors by saying the children were only “helping” and not on the payroll. As they got older, they spent more and more time helping until they began working full-

“The overseer said apologetically, “She just happened in.” She was working steadily. The mills seem full of youngsters who “just happened in” or “are helping sister.” Newberry, South Carolina.”[Hine]

“Little Fannie, 7 years old, 48” tall, helps her sister in Elk Cotton Mill in Fayetteville, Tennessee, November 17, 1910. Her sister said, “Yes, she helps me right smart. Not all day but all she can. Yes, she started with me at 6 this mornin’.” The two girls belong to a family of 19 children.” [Hine]

“One of the spinners in Whitnel Cotton Mill. She was 51 inches high. Has been in the mill one year. Sometimes works at night. Runs 4 sides – 48 cents a day. When asked how old she was, she hesitated, then said, “I don’t remember,” then added confidentially, “I’m not old enough to work, but do just the same.” Out of 50 employees, there were ten children about her size. Whitnel, North Carolina.” [Hine]

Early investigations of conditions in southern cotton mills made it appear to be a regional problem until it was discovered that many of them were owned by northern capitalists. [Child Labor]

Yup. There was enough blame to go around for the child labor issues of the cotton mills.

In any event, here is one of Uncle Sam’s many nieces, “enjoying” an “innocent pastime.” For a minute.

“A moment’s glimpse of the outer world. Said she was 11 years old. Been working over a year. Rhodes Mfg. Co. Lincolnton, North Carolina.” [Hine]

But see, this is all ancient history. Right? It’s irrelevant to the America of today. Right? We “fixed” all that long ago. Right?

Wrong.

But before we consider why it’s not irrelevant, and how pitifully broken many things still are that we think were “fixed” in our country’s history, we need to examine just a bit more of this ugly, mostly ignored topic.