Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

The Rise of Big Brother, Part 3

Burning More Than Draft Cards

“The administration asserts the right to fill the ranks of the regular army by compulsion…. Is this, sir, consistent with the character of a free government? Is this civil liberty? Is this the real character of our Constitution? No, sir, indeed it is not…. Where is it written in the Constitution, in what article or section is it contained, that you may take children from their parents, and parents from their children, and compel them to fight the battles of any war, in which the folly or the wickedness of government may engage it? Under what concealment has this power lain hidden, which now for the first time comes forth, with a tremendous and baleful aspect, to trample down and destroy the dearest rights of personal liberty?”

Guess by whom, where, and when the speech excerpt above was delivered. I’ll follow up with the answer in a few paragraphs.

I graduated from high school in June 1964, and entered college in the fall of that year, just as the US military involvement in Viet Nam was heating up. That left me keenly aware of The Draft. As a female, I wasn’t subject to this potential governmental disruption of my life. But plenty of my male friends were. And very early on, some of them didn’t take it lying down. In May 1964, the first of the Draft Card Burnings took place.

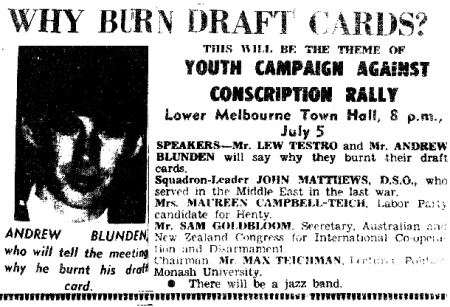

Oh. Wait. That isn’t a poster from the US in the Viet Nam Era…that’s from Australia! Yes, they had their own draft resistance when their government started drafting men to be sent to fight in Viet Nam, and young men there borrowed the draft card burning idea from their contemporaries in the US. That poster is from Melbourne in 1966. Here is a pic of a home-

Although I was aware of the draft in 1964, I actually had no concept of when and how it had become a part of the American Way of Life. And, in fact, only in recent times have I looked into the history of the institution of “conscription”—forced military service—in the US.

I don’t remember what my assumptions were back in my teen years, but I think it was likely that I just assumed the US federal government had, from Colonial Times, put in place a system that could draft men into a national army, to be used if and when the country was threatened by external military forces. If so, I would have been wrong.

In America before 1862, combat duty was always voluntary, but white men aged 18 to 45 were usually required to join local militia units. Colonial militia laws—and after 1776 those of the states—required able-

In 1814, President James Madison proposed conscription of 40,000 men for the army, but the War of 1812 ended before Congress took any action. An 1840 proposal for a standing army of 200,000 men included conscription, but it never passed and military service was voluntary before 1862.[Wiki: Conscription]

The quote at the beginning of this section was made in 1814 in relation to Madison’s proposal for conscription. It was delivered by Daniel Webster in a speech in the US House of Representatives, in protest against the conscription bill being considered in Congress. Webster was very passionate about the topic:

The services of the men to be raised under this act are not limited to those cases in which alone this Government is entitled to the aid of the militia of the States. These cases are particularly stated in the Constitution — “to repel invasion, suppress insurrection, or execute the laws.”

The question is nothing less, than whether the most essential rights of personal liberty shall be surrendered, and despotism embraced in its worst form. When the present generation of men shall be swept away, and that this Government ever existed shall be a matter of history only, I desire that it may then be known, that you have not proceeded in your course unadmonished and unforewarned. Let it then be known, that there were those, who would have stopped you, in the career of your measures, and held you back, as by the skirts of your garments, from the precipice, over which you are plunging, and drawing after you the Government of your Country.

…The administration asserts the right to fill the ranks of the regular army by compulsion. It contends that it may now take one out of every twenty-

Is this, Sir, consistent with the character of a free Government? Is this civil liberty? Is this the real character of our Constitution? No, Sir, indeed it is not. The Constitution is libeled, foully libeled. The people of this country have not established for themselves such a fabric of despotism. They have not purchased at a vast expense of their own treasure and their own blood a Magna Carta to be slaves.

I’d never seen this speech before I began research for this Series. I’m suspicious it may have been quoted a number of times back at the height of the Anti-

No, there had been no national draft until the Civil War. At the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, both Union and Confederate leaders may have felt that their causes were so compelling that the men in their “nations” would gladly swell the ranks of the armies as volunteers. This may have been true at the beginning of the war, but it wasn’t long before disillusionment of the common man set in, and fewer and fewer came forward.

At that point, unable to raise enough soldiers to fill the needs of their military forces by volunteers, both sides in that ignominious war resorted to creating a system of conscription.

The Confederacy had far fewer inhabitants than the U.S., and Confederate President Jefferson Davis proposed the first conscription act on March 28, 1862; it was passed into law the next month. Resistance was both widespread and violent, with comparisons made between conscription and slavery.

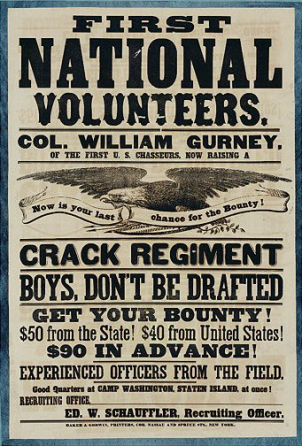

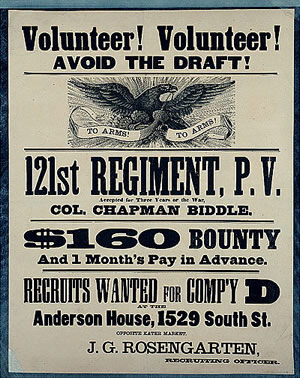

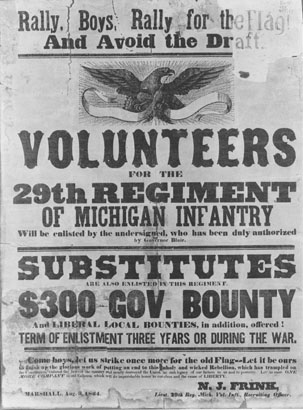

Both sides permitted conscripts to hire substitutes to serve in their place. In the Union, many states and cities offered bounties and bonuses for enlistment. They also arranged to take credit against their draft quota by claiming freed slaves who enlisted in the Union Army. [Wiki: Conscription in the United States]

Although both sides resorted to conscription, the system did not work effectively in either. The Confederate Congress on April 16, 1862, passed an act requiring military service for three years from all males aged eighteen to thirty-

…In the Confederacy, the “Twenty Negro Law” permitted one owner or overseer of any plantation to exempt themselves from military service; this proved extremely unpopular with many Confederate soldiers and contributed to the oft-

Resentment and resistance was much worse in the North, culminating in the July, 1863 “New York Draft Riots.”

The New York City draft riots (July 13 to July 16, 1863; known at the time as Draft Week) were violent disturbances in New York City that were the culmination of working-

President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops from following up after the Battle of Gettysburg [which had occurred only two weeks earlier] to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly working-

Some historians note that a major precipitating factor bringing on the riots was that political leaders of the time had persuaded many immigrant Irishmen to apply for citizenship so that they could vote. What these new voters didn’t realize until too late was that their new status would also make them liable to being drafted!

The Democratic Party political machine of Tammany Hall had been working to enroll immigrants as U.S. citizens so they could vote in local elections, and had strongly recruited Irish, most of whom already spoke English. In 1863, with the war continuing, Congress passed a law to establish a draft for the first time, as more troops were needed. In New York City and other locations, the new citizens learned that they were expected to register for the draft to fight for their new country. Black men were excluded from the draft as they were not considered citizens, and wealthier white men could pay for substitutes. Free black men and immigrants competed for low-

… There were reports of rioting in Buffalo, New York, and certain other cities, but the first drawing of numbers on [Saturday] July 11, 1863 occurred peaceably in New York City. The second drawing was held on Monday, July 13, 1863, ten days after the Union victory at Gettysburg. At 10 a.m., a furious crowd of around 500, led by the Black Joke Engine Company 33, attacked the assistant Ninth District Provost Marshal’s Office, at Third Avenue and 47th Street, where the draft was taking place. The crowd threw large paving stones through windows, then burst through the doors and set the building ablaze. When the fire department responded, rioters broke up their vehicles. Others killed horses pulling streetcars and smashed the cars. To prevent other parts of the city being notified of the riot, they cut telegraph lines.

But the destruction of the draft office was only the beginning of the rage. The crowds began roaming the streets of New York and destroying everything in their path.

… The Bull’s Head hotel on 44th Street, which refused to provide alcohol to the mob, was burned. The mayor’s residence on Fifth Avenue, the Eighth and Fifth District police stations, and other buildings were attacked and set on fire. Other targets included the office of the New York Times. The mob was turned back at the Times office by staff manning Gatling guns, including Times founder Henry Jarvis Raymond. Fire engine companies responded, but some of the firefighters were sympathetic to the rioters, since they too had been drafted on Saturday.

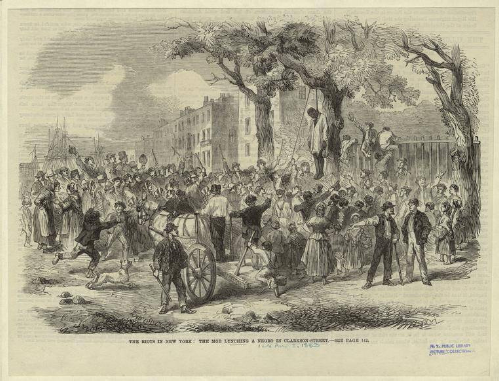

…Rioters turned against black people as their scapegoats and the primary target of their anger. Many immigrants and the poor viewed free black men as competition for scarce jobs, and worried about more slaves being emancipated and coming to New York for work. Some rioters thought slavery was the cause of the Civil War. The mob beat, tortured and/or killed numerous black people, including one man who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then lynched—hanged from a tree and set alight. [Actually, 11 black men in all were lynched during the riots, with at least another 100 blacks killed. At least 20 whites were killed, and likely over 2000 people wounded.] [Source]

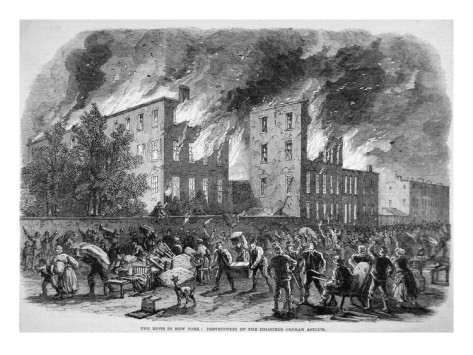

The military did not reach the city until after the first day of rioting, when mobs had already ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was burned to the ground. [ibid]

Yes, not even young children escaped the mindless wrath of the mad mob.

The rioters’ targets initially included only military and governmental buildings, symbols of the unfairness of the draft. Mobs attacked only those individuals who interfered with their actions. But by afternoon of the first day, some of the rioters had turned to attacks on black people, and on things symbolic of black political, economic, and social power. Rioters attacked a black fruit vendor and a nine-

At 4 P.M. on July 13, “the children numbering 233, were quietly seated in their school rooms, playing in the nursery, or reclining on a sick bed in the Hospital when an infuriated mob, consisting of several thousand men, women and children, armed with clubs, brick bats etc. advanced upon the Institution.” The crowd took as much of the bedding, clothing, food, and other transportable articles as they could and set fire to the building. John Decker, chief engineer of the fire department, was on hand, but firefighters were unable to save the building. The destruction took twenty minutes.

In the meantime, the superintendent and matron of the asylum assembled the children and led them out to Forty-

It’s not clear from the record how many rioters may have taken part in the four days of rioting, but since it took 4,000 armed soldiers to put an end to the rioting, there were no doubt several thousand people involved.

I had never heard of the New York Draft Riots of 1863 until a short time ago. But when I mentioned the topic to my husband, I was surprised to find out he knew a lot about them. Not because he is a reader of history books…but because he saw Martin Scorsese’s 2002 movie Gangs of New York, that starred Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Day-

Set in 1863 New York, the climax of the film is a recreation (not totally historically accurate, but very effective in accurately portraying the mood, the look, and the level of violence of the event) of the Draft Riots. Here is a link to a clip of 3 minutes or so of that cinematic climax. I do not doubt in the slightest that the real-

I share all this preliminary information to make clear just what a risk the US government was taking in 1917 in choosing to establish conscription as a major building block in its World War 1 military planning.

This was the nation’s first experience with mass conscription; drafted men made up just 8 percent of soldiers in the Union army during the Civil War, but they constituted 72 percent of Uncle Sam’s forces in World War I. [Uncle Sam Wants You: World War 1 and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (USWY)]

This is not to say that the government didn’t make an effort to “learn the lessons” of the Civil War draft fiasco.

… The Selective Service Act of 1917 was carefully drawn to remedy the defects in the Civil War system and—by allowing exemptions for dependency, essential occupations, and religious scruples—to place each man in his proper niche in a national war effort. The act established a “liability for military service of all male citizens”; authorized a selective draft of all those between 21 and 31 years of age (later from 18 to 45); and prohibited all forms of bounties, substitutions, or purchase of exemptions. … In 1917 10 million men were registered. This was deemed to be inadequate, so age ranges were increased and exemptions reduced, and so by the end of 1918 this increased to 24 million men that were registered with nearly 3 million inducted into the military services, with little of the resistance that characterized the Civil War, thanks to a huge campaign by the government to build support for the war, and shut down newspapers and magazines that published articles against the war. [USWY]

Yes, this time the draft wasn’t limited to poor working men from the ghettos.

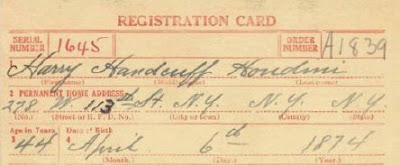

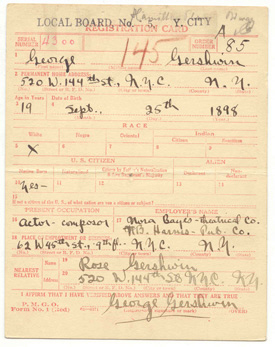

Harry Houdini, age 44 and already famous at the time, whimsically listed his middle name on his registration as “Handcuff.” George Gershwin, only 19 at the time, already listed his occupation as actor and composer.

And that brings us back to the American Protective League—the beginning of the rise of Big Brotherism in America. No, there was no one central Big Brother, no Fuehrer, no Hitler or Stalin or Mao-

It turns out it was “We The People,” self-

America’s vaunted culture of voluntarism intersected with and amplified state power, rather than acting as a check on it.

A Big Brother “state” did not develop a clandestine program for identifying and recruiting a cadre of snitches and bullies—the snitches and bullies came blatantly knocking down the door of the government in Washington in broad daylight, demanding to be given authority…and endorsement for their own narrow vision of “whipping the country into shape” for the war effort.

“Civil liberties? Civil rights? Protection from unreasonable search and seizure? HooHah!” said the pseudo-

And thus arose the Slacker Raids. Come along and join the Merry Band o’ Raiders.