Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

The Rise of Big Brother, Part 6

Big Sister Is Watching You

World War 1 “slackers,” men who tried to avoid the war-

Our examination of the American Protective League’s activities during the war specifically focused on the men of the United, from the declaration of war on April 6, 1917 to the armistice on November 11, 1918. And it described the incredible level of “volunteer” surveillance going on in the country—male citizens spying on, tattling on, and strong-

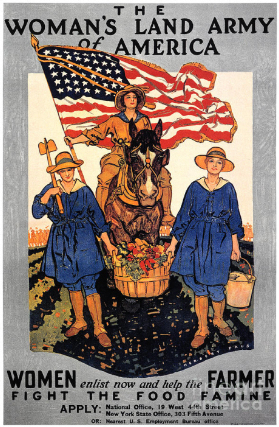

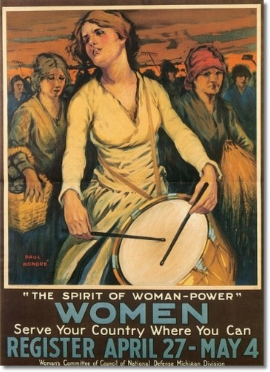

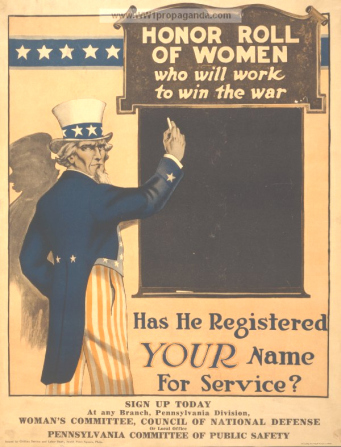

But that could leave an inaccurate perspective on the role played by American women during the Great War. Some posters from the period may leave the impression that women’s main role was just to “give reason”—as wives and mothers—for men to go off to war, staying home to “keep the home fires burning” for when the men would return victorious.

Most modern folks seem aware of the role that women played in World War 2, particularly as a result of the continuing popularity even today of the famous Rosie the Riveter “We Can Do It!” poster, and Norman Rockwell’s rendition of Rosie for a May 1943 cover of the Saturday Evening Post. (The generic name Rosie the Riveter was used as shorthand to refer to all the women who had stepped in to “do a man’s job” … such as using riveting guns to piece together metal in the munitions industry.)

But I’ll bet many…including me until recently…haven’t realized how involved women were also in World War 1. Yes, they were needed back then in the factories also, with so many men leaving their jobs to go off to the war front, such as these women making bombs.

…and these making machine guns.

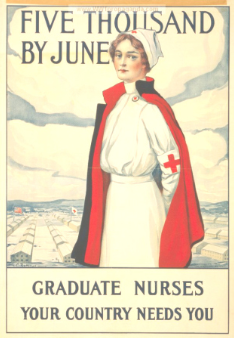

Many women also served as Red Cross nurses …

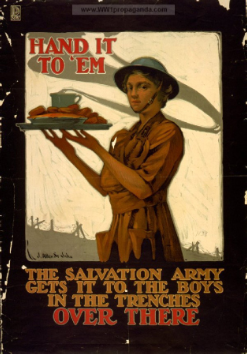

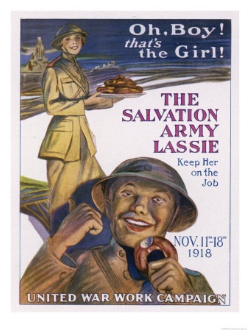

…and in various functions in the Salvation Army.

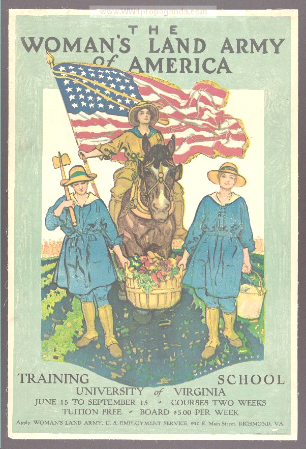

Then there was the “Woman’s Land Army.” American crops were desperately needed to feed the US population, to feed our own soldiers and those of our Allies on the front lines in Europe, and also for the starving populations in many war-

The city slickers were even given a crash course in farming, sort of like a boot camp!

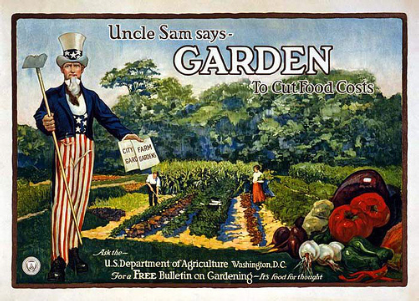

These active female roles in the war effort, some even close to the front lines, were filled more often than not by single young women. But what of younger married women with children, and women perhaps too old to do factory labor? There was a common expectation that everyone ought to be taking some sort of active role in the war effort, by at least purchasing War Bonds, and also by cooperating with all sorts of programs promoted by the government. Posters encouraging “Victory Gardens” were plastered everywhere—every woman who had access to even a small plot of ground was encouraged to organize her family to “grow their own” vegetables.

Uncle Sam promoted the gardening craze, as did his girlfriend Columbia.

Those who didn’t participate whole-

And thus there arose “Bands of Big Sisters” to deal with them. To spy on them, tattle on them, and strong-

Just as with the rise of the APL, these were not groups imposed from the top down by the government, but grass roots, volunteer, in many cases vigilante groups. And one might think that they arose because of an extended period of “brain washing” by government propaganda, like that in Orwell’s dystopian future of 1984, forcing them to “group think.” No, this was not the case. Strangely enough, in 1916, much of the country, and particularly the women of the land, tended to a position, regarding the “European War,” of neutrality at least, and often of pacifism. In early 1917 even President Wilson was still taking a stand against US involvement. There WAS no government pro-

There is no doubt that very soon the government did develop an elaborate program of propaganda, through the “Committee for Public Information.” And that program did tend to play upon the hysteria already present. But it didn’t cause it. The initial zeal of so many groups, including the APL and the “General Federation of Women’s Clubs” that will be mentioned below, seems to have been truly a grass roots phenomenon.

It was NOT necessary to have a period of “brain washing” or “indoctrination” by government propaganda to get women to spy on one another. They were more than ready and willing as soon as they were given opportunity.

Diatribes against the “woman slacker” soon filled the popular press and the minutes of women’s clubs. A wartime editorial in Ladies’ Home Journal described the woman slacker as “a woman who cannot take anything seriously, . . . who cannot put aside her little dolls and playthings: who must consume in social frivolity the time and strength that other women are putting into salvatory work.” Selfishness perplexed the politically engaged women who were daily giving all to the nation. Like the draft dodger and the conscientious objector, the woman slacker had cast off the burdens of citizenship with a shrug of her shoulders, leaving others to carry the load. [From Uncle Sam Wants You: World War 1 and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (USWY). Unless otherwise noted, all quotations in this entry are from this source. Any underlining, bolding, or italics in quotations have been added for emphasis.]

Although some men came forward and volunteered for military service with little or no prompting at all after war was declared in 1917, it took a concerted program of enlistment posters, the draft, and other types of encouragement to mobilize the huge army necessary to do America’s part in winning the war. The same was true for getting women involved in war work. There was a flurry of enthusiasm among some women to get involved, but without some coordinated supervision, many worried that it would be ineffective.

Government officials and leaders of major organizations also worried that uncoordinated voluntarism would be inefficient. Among draft-

Reckless female voluntarism was different, frequently dismissed as a frivolous search for entertainment that needed to be controlled rigorously lest it detract from the serious business of war. Student Anna Davenport Sparks told her Smith College classmates that their service, “if it is to be efficient, must not be in an orgy of enthusiasm, but rather in sane, well-

The Ladies’ Home Journal urged readers to serve but serve smartly: “Let every woman … be sure of her talent, and not hinder or complicate by offering herself for work for which she is not fitted.” These concerns reflected the political culture of the era.

Even worse than uncoordinated efforts would be efforts that were all “show” destined to bear no fruit—merely “playing at” volunteer work.

No one could quite decipher what women’s wartime voluntarism was; since it wasn’t work, they feared it might merely be leisure. And so the nation’s clubwomen attempted the same solution the War Department did: selective service under a broad regime of voluntary registration.

During the early months of the war, women’s organizations canvassed their members, dutifully filling note cards with lists of skills that might be useful to the war effort: nursing, sewing, driving, shooting.

Philadelphia women gathered ninety-

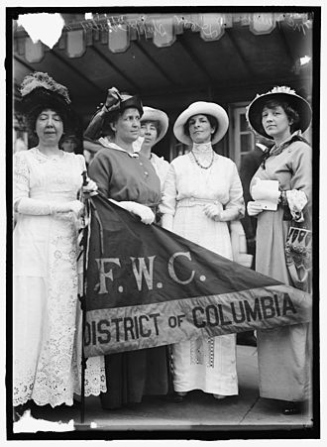

The General Federation of Women’s Clubs was founded in 1890. Leaders of a Federation delegation to the White House in 1914 are shown here.

It’s still an active organization:

Accomplishments during GFWC’s first century include: establishing 75 percent of the country’s public libraries, developing kindergartens in the public schools, and working for food and drug regulation.

GFWC clubwomen are true volunteers in action—in 2009, GFWC members raised over $39 million on behalf of more than 110,000 projects, and volunteered more than 4.1 million hours in the communities where they live and work. [Wiki article on GFWC]

In some ways, the GFWC functioned in a similar way to the APL during the war years.

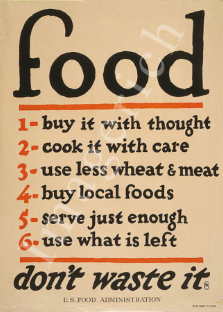

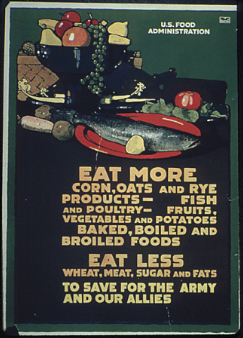

Their first task was to establish a unified home-

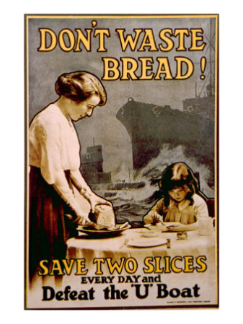

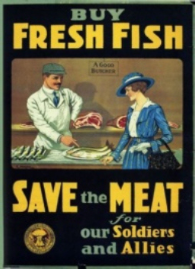

The government cooperated in helping remind everyone of such pledges through posters. Bread was the focus of many of these, because wheat was considered one of the most important exports necessary for the soldiers at the front. Homemakers were encouraged to severely limit the amount of wheat baked goods and cereals that their family ate, substituting corn and rice and other grains.

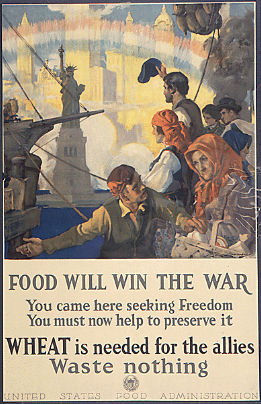

Special groups, such as immigrants, were even targeted by some posters.

The rank and file responded wholeheartedly. The New York State Federation of Women’s Clubs supported food conservation in a November 1917 resolution; Dallas women joined in, too. Thirteen thousand Minnesota clubwomen signed the GFWC pledge. Women’s clubs expanded their pledge drives nationwide under the auspices of the U.S. Food Administration, and as they blended state action and civic voluntarism, they also began to blur the line between mobilization and social control.

The Hoover Pledge Drives—so called because they were administered by U.S. Food Administration and its director, although in fact Herbert Hoover had very little to do with them—sought the signature of every woman who ran a household.

By the time that blank Hoover Pledge Cards began circulating across America, thousands of clubwomen had long since pledged their loyalty, and these volunteers—almost 500,000 of them—now turned their attention to women outside their own organizations, explicitly taking on the task of regulating the political obligations of other women. Responding to a series of three drives in June and October 1917 and June 1918, as many as fourteen million households signed the pledge.

And make no mistake, the “pledge” was viewed by most as much more than just an idle promise.

Women’s adherence to their pledges was also enforced. “Anyone neglecting or refusing to comply with our government’s food regulations will be marked as a traitor in the community,” announced South Dakota’s Food Administration head in 1918.

P. M. Harding, who ran the USFA in Vicksburg, Mississippi, announced public hearings, “so that persons failing to co-

And just how did Mr. Harding expect to know that any given family was ignoring the food regulations at their family dinner table? There would have been no bayoneted soldier going door to door at dinnertime to see if little Johnny was not eating all his food, or Mother was being too generous with piling portions on Dad’s plate, or serving beef too often instead of fish or chicken.

No, no soldier would be needed. Just nosy neighbor ladies.

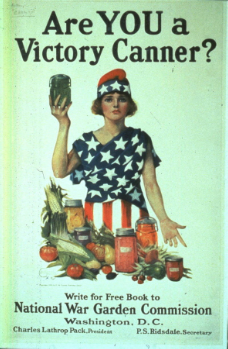

Sugar was another important food item which citizens were urged to conserve. It could be used in canning certain food items, as part of a diligent effort on the part of women to preserve food from their family victory garden to get through the winter.

In Macon, Georgia, in July 1918, Emma Furman’s daughter Bess returned from the Red Cross knitting circle with news that a neighbor, who had been permitted to purchase twenty-

“She was visited by authority and ordered to show the preserves or the sugar,” Furman noted in her diary. “Not being able to do either [she] was put under a $300 bond.”

Furman didn’t pause to identify the “authority” in question, perhaps because authority at that moment was so diffuse.

You can bet that no official government agent was bothering to go door to door to check for “sweets” in houses across the land. They didn’t need to. I have little doubt that some of this lady’s own friends or neighbors tattled on her, perhaps after stopping by her house for tea and noticing the fresh baked sweets on the counter in her kitchen.

Or maybe someone right inside the home might tattle.

Compulsion could even be internalized within the household itself.

Mary Aldis found half a slice of bread in her kitchen garbage can during the war. She recounted to readers of the Journal of Home Economics how she “call[ed] my household staff together” and “asked who was the guilty one.” Hanging in Aldis’s kitchen? Not only the Hoover Pledge poster, but also a sign, “in red letters”: “To waste a crust of bread is an act of treachery to the nation.”

Gives new meaning to “hyperbole,” doesn’t it!

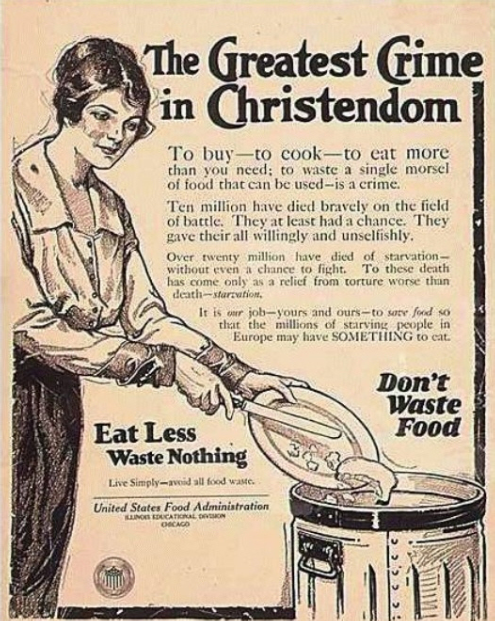

Yes, hyperbole was often the method of choice on posters at the time, such as this one about the “Greatest Crime in Christendom”:

Whatever level of nosiness neighbor ladies may have naturally had, it was magnified and legitimized by all sorts of people in authority.

At times, women’s efforts brought them foursquare into the dynamics of home-

Settlement house workers at New York City’s Greenwich House collaborated with army and navy intelligence bureaus. The New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs established an espionage committee, “asked to be ‘eyes and ears’ for the government, to report suspicious actions, seditious remarks, interference with government meetings and the circulation of false reports concerning war organizations.” Members boasted that “reports sent through this committee to the Department of Justice at Washington were of material assistance to the government.”

Yes, all across the land, the reality was that “Big Sister Is Watching You.”

Americans who wanted to do their part for the war found explicit instruction in an editorial in New York State’s Albany Journal akin to those published in thousands of wartime newspapers: If you ever, on the street or in a trolley car, should hear some soft-

Every American, under provisions of the code of civil procedure, has the authority to arrest any person making a remark or utterance which “outrages public decency.”

And all across the nation, among the men of the APL, and the women of the various women’s organizations, this concept of vigilantism was embraced. However, by the end of the war, it had become obvious to even some of the most enthusiastic that this wasn’t necessarily always a good thing.

In Seattle, Washington, during this era there was a group called the Seattle Minute Men that eventually merged its efforts with the APL. Author Susan Newsome notes the following in an article titled “The Seattle Minute Men: Amateur Spies, Gossip and Lies”:

The methods used by the Minute Men and the information they supplied was often questionable. There are numerous reports that lack evidence other than simple gossip or that show a definite dislike by the agent for the subject he is investigating. Herein lies the greatest problem with volunteer spy organizations such as the Minute Men or the American Protective League: They are not held accountable for their actions or the results thereof. To begin with, many of the reports submitted were lacking any basis for an investigation. Stating that a certain man or woman is pro-

A good example of one such frivolous report is dated February 21, 1918 reported by C.F.B. The report is based on a complaint from Mrs. Chas. F. Boyd who was not pleased that Mrs. Emory Winship, whose husband was in charge of the Navy Recruiting Office at Bremerton, had a German born maid. Mrs. Winship had testified that her maid was, “as much American in feeling as anyone could be.” Mrs. Boyd felt that someone should do something about this German woman, “on the grounds that this is a poor time to be taking chances on the loyalty of a German woman working in a place where it is possible for her to pick up valuable information for the enemy.” The reply to this report stated that Mrs. Boyd was an overly suspicious woman and over-

Many people today have great concern about the “intrusiveness” of technological surveillance in the US. The latest news about the National Security Agency and its secret (well, formerly secret…) gathering of massive amounts of data from telephone and email traffic, as well as from internet social media such as Facebook certainly brings up visions of Big Brother and Orwell’s dystopian vision of 1984. What concerns ME is that so many folks seem to think this is “some new thing” in America, and mostly evidence of a plot by the current administration to impose some sort of totalitarian regime. There is much hand-

I find this incredibly naïve. There has never been a technology that wasn’t almost immediately used…in this country and around the world…in intrusive ways by the authorities. And, in fact, in some ways the intrusions into freedom of speech and freedom of communication were MORE Orwellian a century ago than now, even though the technology was far simpler. Yes, computerized meta-

And consider the modern concerns about the “Mainstream Media” being a stooge of the administration as many claim today, helping it to establish an Orwellian grip on the populace—back 100 years ago, the government imposed a complete blackout on ALL news in ALL newspapers having even the slightest thing to do with the war effort, other than official news reports provided by the government itself. Absolutely NO speculation or criticism was allowed in the press regarding governmental decisions.

“Regulations for the Periodical Press of the United States during the War.” These regulations— they were not billed as “Guidelines” or “Suggestions,” but as “Regulations”— carefully divided news into three categories, “Dangerous, Questionable, and Routine,” each to be treated differently. Within the “Dangerous” category were three subcategories, “General, Naval, and Military.”

The list of forbidden items under the “General” rubric included all stories of naval and military operations in progress, except for what was officially given out; the movements of official missions; threats against the life of the president; news relating to the Secret Service or confidential agents; and the movements of “alien labor”— that is, foreign-

The “Regulations” placed under the “Questionable” heading all matter that might be acceptable for publication, but only with caution— and, usually, only with the explicit approval of the CPI. Here Creel fudged, declining to offer a detailed listing, but instead suggested some example subjects, including training camp routine, technical inventions, and the publication of rumors, especially those of a sensational nature (such as the outbreak of an epidemic in a camp). Anything outside of the “Dangerous” and “Questionable” categories was deemed “Routine,” which meant that it could be published without prior approval; however, Creel urged editors to submit to the CPI anything about which they entertained even the slightest doubt. Such articles would be reviewed and stamped “Passed by the Committee on Public Information,” which meant that they contained no objectionable material but had not been checked by the CPI for accuracy, or “Authorized by the Committee on Public Information,” which meant that the material had been both cleared in terms of security and, after investigation, had also been found to be factually accurate.

And there was no email, but…

…almost immediately after the declaration of war, President Wilson ordered the U.S. Navy to seize all commercial “wireless establishments” (radio stations) and ordered radio operators, amateurs and professionals alike, to cease broadcasting. On April 28, three days after Koons’s order to postmasters, Wilson issued an executive order tightly clamping down on cable, telephone, and telegraph messages leaving or entering the United States.

In other words, during the War there was no such thing as “investigative reporting.” All reporters having anything to do with reporting on the war were taken under the wing of the government, not employees of independent news-

The U.S. Army and Navy thought they needed near-

Whereas conventional censorship was designed to keep the press out, Creel’s plan was to take the press in. Whereas conventional censorship was designed to stop the flow of information, Creel’s army of journalists, pledged to government service, were “to take the deadwood out of the channels of information, permitting a free and continuous flow.” The trouble with censorship as conventionally conceived was that it created a vacuum where the people’s perception of reality should be. Popular opinion, sentiment, and belief all abhor a vacuum. Denied information, the people will look to whatever sources present themselves— enterprising reporters, rumor mongers, panic-

…Under the CPI war regime, news was not to be the result of investigation, the proprietary product, as it were, of private enterprise, but public property to be apportioned equally to all. The Creel Committee effectively nationalized the news. Not only did it come from a government source, it was treated as government property.

In 2016 one of the biggest issues for many Americans is the way that the current administration—and recent administrations—in Washington justify tampering with the freedom and privacy rights of Americans by insisting it is necessary for the common defense. But this is precisely how the administration 100 years ago justified its tampering too, and in many ways I find their approach to have been even more suffocating. Modern administrations may be listening in to the criticism of their policies all over the Internet, but it does very little to stop such criticism. You really can still get away with calling Obama the Antichrist on your blog, and threatening the government on your Facebook page with armed rebellion if they try to take your guns away.

And newspapers and cable news shows can get away with just about any criticism they can throw, no matter how nasty. This was NOT possible a century ago in the media of the time! If you tried to get on the Facebook of the time…the conversational crowd around the pickle barrel at the local grocery store…and indulge in a rant about the president, you didn’t have to worry about an FBI spy collaring you—the sweet little old lady from down the street would take care of the job for him.

Yes, “Big Sister Was Watching You.” As was Big Brother, Li’l Brother…and almost everybody else.

Many of my friends are now paranoid about the power of the governmental Users of Big Technology. I don’t blame them—the possibilities are pretty scary. But I am convinced that there is a power more powerful than that, which they would do well to worry more about:The power of the misguided zealotry of the common man. It is not bounded by time in history, or by the need for technology, although it can harness technology to its own purposes.

We see it in the Bible, both Old and New Testaments. I’m put in mind of the Apostle Paul before his conversion. The fears of the earliest Christians weren’t just about the secular Big Government of the Roman authorities, with its armies and its modern effective road and communication systems. The misguided religious zeal of a Paul was enough to strike just as much fear in any of them.

Galatians 1:13-

For you have heard of my previous way of life in Judaism, how intensely I persecuted the church of God and tried to destroy it. I was advancing in Judaism beyond many of my own age among my people and was extremely zealous for the traditions of my fathers. (NIV)

Acts 8:3

But Saul began to destroy the church. Going from house to house, he dragged off both men and women and put them in prison.

9:1-

I am personally convinced that average Americans ought not to view their biggest worry about the future as an Orwellian-

I suggest that they may eventually find instead that they should have been more worried about the fruit of a grass roots swell of misguided zeal of their own neighbors.