Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

The Rise of Big Brother, Part 4

Band of Big Brothers

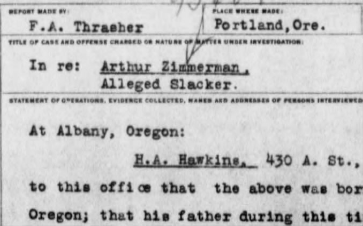

The US Government was far too busy at the beginning of the US involvement in WW1 to place a major federal emphasis on trying to track down draft-

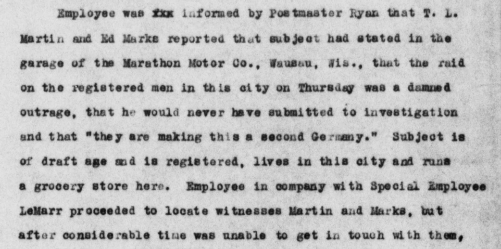

Voluntarism also shaped the “slacker raids,” vast dragnet operations of interrogation conducted by the 250,000 volunteer members of the American Protective League. … the American Protective League put a local face on a distant federal power, but that power was only possible in the first place because citizens voluntarily participated in the league. This was what bottom-

The idea for slacker raiding developed from within the American Protective League itself. The Bureau of Investigation depended on the APL’s detective work, and many operatives—even if they were not technically authorized to make arrests—did so. (They also eagerly claimed the $50 rewards that the U.S. Army offered for the delivery of alleged deserters to military camps.) Similarly, league men had been making individual interrogations and small-

The federal government had done its part in trying to bring down the numbers of those avoiding the draft, including through hard-

But that wasn’t enough, and it appeared as if hundreds of thousands of men were shirking their patriotic duty. So…

In the spring of 1918, authorities in the War Department, responding to the offers of the eager patriots of the APL, contemplated using their services to bring in slackers.

…Its first citywide sweeps took place in Minneapolis and Pittsburgh on March 26, 1918…These were followed by the first multi-

The Chicago incident typified slacker raids nationwide. For one thing, a wide variety of men claimed the authority to detain possible slackers. Chicago’s APL operatives joined professional Department of Justice agents, city police, and soldiers and sailors on furlough in the city. Evidence from the Chicago raids and later ones in New York suggests that despite the presence of military personnel and local police, the Justice Department and the APL called the shots; the league handled about 75 percent of Chicago’s cases. [All further quotations in this section are from USWY]

What was a slacker raid like?

The Chicago slacker raid was a thoroughly modern phenomenon. It targeted places of mass entertainment and congregation: railroad stations, movie theaters, even a baseball game at Comiskey Park. It used automobiles to shuttle detainees across town, as well as telephones and telegrams to communicate with their draft boards. The scope and scale of the Chicago raid testify to the APL’s ambition; this was no Sunday picnic. Modern bureaucracy came in handy, too: what happened to a man during a slacker raid had little to do with his political views or, ironically enough, whether he was actually liable for military service. What mattered was his ability to demonstrate a state-

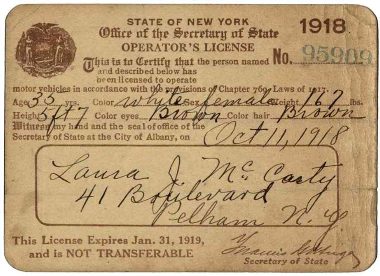

Those of draft age were expected to carry their registration card with them at all times. But draft registration had only been around for a few months. Remembering to put your draft card in your pocket every time you stepped outside your home was no doubt a habit instilled in very few men…before the slacker raids. And what of those men who didn’t “look their age”? The Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917, required men ages 21-

Proof of age might be a driver’s license…which a large proportion of young men would not have possessed, since only 1 in 13 families in the US owned a car in 1918. Or it could have been a birth certificate. But how many people, even today, go around with a copy of their birth certificate in their pocket? Most people back then probably didn’t even own a copy of such a certificate. The original would just reside in a court house somewhere.

The zealous APL men had absolutely no interest in the issue of false arrest. They had invented a job to do, and they did it with a vengeance. To very little good purpose, as it turned out.

As would be repeated nationwide, the number of draft evaders rooted out during Chicago’s raids was trifling in comparison with the effort required to carry them out. Questioning in Chicago yielded some 20,000 detainees (mostly for failure to carry identity cards), of whom 1,200 alleged draft evaders were turned over to army authorities; nearly all were hastily released. These dismal results would be reproduced in cities across the country during the summer of 1918.

The Chicago slacker raid met with general approval. The Spy Glass, the APL’s official newsletter, noted that “there was little or no disturbance and few attempts to resist the authority of the League men who conducted the roundup. Most of the young fellows took their arrest as a disagreeable joke due to their own neglect and waited patiently until their identification could be completed.”

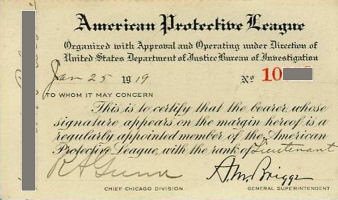

The power of the APL was not just regional. Men from all parts of the country were eager to possess an imposing membership card, wear a flashy badge, and take part in slacker raids!

…Slacker raiding reached a fever pitch in the late summer of 1918, with raids at New York City’s Coney Island on July 21 and in Trenton on August 2 (with a follow-

They also raided Los Angeles, as shown in this headline clipped from an August 1, 1918, Los Angeles paper, with the heading “Slacker Suspects.”

And that brings us to New York City. Just fifty years earlier, New York City had been the site of the horrendous four-

But of all the earlier drives, none matched the New York City slacker raids of September 3 to 5, 1918—in size or in controversy.

…For the patriot volunteers of the American Protective League, the time for action was now. And the place for action was New York City: “we find that the great states of each coast are practically foreign—New York most of all,” bemoaned Emerson Hough. The War Department offered its own bit of foreshadowing for the raids, announcing in New York newspapers on September 1 that “a great organization, extending into every State … has been constructed to hunt down those attempting to evade the new selective service law.” As Provost Marshal General Enoch Crowder noted in the same article, “The registrant’s protection is to have with him at all times his registration cards.… Failure to carry these credentials will render him liable to arrest at any time.” The Justice Department would later point to this article as “fair warning” of events to come.

Conveniently, the Justice Department also shut down the offices of the New York Civil Liberties Bureau and the New York Bureau of Legal Advice two days before the raids.

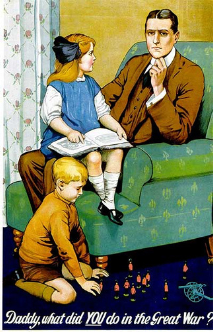

I’m always surprised at people today who rant how their “rights as citizens” are being trampled on by whatever regime is present in Washington, as if this is some new thing! And when they do, it is often for the most minor irritation.

How would they have liked to have been a 22-

Beginning at 6:30 A.M. on a hot, sticky day with on-

The APL later estimated that somewhere between twenty thousand and twenty-

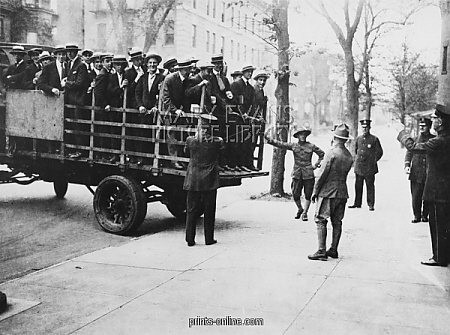

A man who lacked a draft registration or classification card found himself escorted by these self-

Yep, they were herded just like cattle, as can be seen from this snapshot taken during that infamous three-

Although some men did complain afterward of rough handling, operatives had been cautioned to be “courteous but firm,” and there is remarkably little evidence of physical violence; the Nation later marveled at “the long-

The raiders began their work that busy Tuesday morning by surrounding the exits and entrances of every train, ferry, subway, and elevated station; before rush hour was over, nearly 2,500 men had been seized from the stations alone.

And there is no question that the raiders had absolutely no sense of “mercy rather than justice” in special cases.

One couple, fresh from their wedding in upstate New York, stepped off the train in Grand Central Terminal and found themselves accosted by a sailor. “We were only married in Plattsburg [sic] yesterday, and you don’t suppose I thought anything about draft board cards?” the husband asked. Unmoved by the couple’s newfound marital bliss, the sailor whipped back, “Hard luck, but you’ll have to come along.”

There was no limit to where they would accost men in their single-

By noon, the raiders had shifted their attention to Manhattan’s midtown and downtown business districts, often cordoning off whole blocks and interrogating the men on the street. Later, they raided theaters, saloons, billiard parlors, and boarding houses. Sailors wandered through the city’s restaurants, moving from table to table inspecting the cards of diners. Frequently, they then moved from the dining room to the kitchen…

Nor did raiders show any partiality to those who were “on their side.”

… By 1:00 P.M., authorities had gathered “a considerable crowd” at Lafayette Place and Fifth Street. A nearby truck driver volunteered to haul the men to the armory at Twenty-

Operatives were soon told to cease interrogating drivers at the wheel because abandoned vehicles were interrupting the flow of traffic.

Nor did the raiders show any favoritism to celebrities.

One of the more dramatic raids took place at the Lexington Avenue Theatre, where soldier-

Confusion ensued, and the investigation was put off until the end of the show, thanks to the intervention of a military officer: Sergeant Irving Berlin, the musical director of Yip, Yip, Yaphank, who was responsible for the men in the cast and furious that his performance had been interrupted.

By the second day of the raid, New Yorkers had already learned to carry their draft cards; the intensity of the raids did not abate, but the number of arrests did. “Young men walking for two or three blocks in Times Square were usually held up six or seven times in that distance, but few complained,” a reporter noted. “Nearly every one had his draft card handy and showed it with a smile.” Many made hasty efforts to document their identities. So many men crowded the offices of the State Military Census Bureau looking for duplicate registration cards that the police had to be called in to disperse the crowd after the forms ran out.

I wonder how many of these super-

By the third day, the draft dodgers still did not appear, and some slacker raiders’ initial enthusiasm began to wane. Others stepped up their methods, raiding a restaurant on the Lower East Side, where they captured a handful of men who had been wanted in association with socialist agitation (although their draft papers were apparently in order). Army privates and military police invaded the city’s financial district, interrupting trading at the Wall Street curb market and closing off the Equitable Building, where they interrogated the building’s seventeen thousand employees. They uncovered just twenty-

You’d kind of think that with up to 500,000 men interrogated in just three days, there would have been a real bonanza of slackers forced to jump on the patriotism bandwagon. Not so.

But authentic slackers and enemy aliens were few and far between. By the end of the three days, 60,187 men had been detained in New York City and its surrounding suburbs. But of these, only 199 were actual draft dodgers who would later end up in military uniform. And the number of “willful deserters”—men who had deliberately ignored Uncle Sam’s call-

So for every real “slacker”…

…there were approximately three hundred men who spent the night in a city jail solely because they could not document their identity, age, or draft registration status to their interrogators.

The next time you are tempted to gripe about how much you think “liberty” in America has been infringed upon in recent years, and to wax nostalgic about how much better you think it would have been a century ago…take a little reality break and consider the Slacker Raids. You didn’t need some central “Big Brother” figure to keep an eye on you back then…you had a whole gigantic Band of Big Brothers ready to box your ears if they even THOUGHT you might have gotten out of line.

But don’t stop there. Let’s examine even more of what it was like to live in the Land of the Free in the Good Old Days of a century ago. Back when you didn’t need to just worry about Big Brother … because the reality at the time was…Li’l Brother was watching you too.