Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8

Not So Fabulous Fifties, Part 4

MAD Music

The Cold War Era spawned a large number of nuclear-

You can listen to one of the co-

As just a tiny taste of the mood of the times during the depths of the Cold War period, I’ll share the stories of three of the classic Atomic Platters. Given the obsession with Mutual Assured Destruction, we might refer to this genre as MAD Music.

First Blast from the Past

“Fallout Shelter”

Singer: Billy Chambers

Composer: Bobby Braddock

Year: 1962

If you’re too impatient to listen to the song … or couldn’t clearly hear the lyrics, here they are.

Refrain: I’d rather die with you than live without you

And I hope that you feel the same.

Mom and Dad and I were getting ready for the game

I couldn’t play tonight, you know, my leg’s still kinda lame

And then I heard my mother call out our Savior’s name

I looked to the east and the sky was filled with flames

Then Dad said don’t worry, we don’t have to be scared

We’ve got our new fallout shelter waitin’ for us there

When I told Dad I’d go get you, he said don’t you dare

There’s no room for your girl, son, that just wouldn’t be fair

Refrain

Then I thought of all the happy times that we had spent together

And the way we pledged our love to each other forever

Could I be there in that shelter with you out here

Rather than hold you in my arms? No, my darlin’, never

Old Uncle Ben, everybody’s friend, sits in there with his gun

The streets are all deserted now, did you see those people run?

You hold my hand, I understand the sickness has begun

And if we live or if we die our hearts will beat as one

Here’s what the Atomic Platters site had to say about Fallout Shelter by Billy Chambers. (There were other songs by the same name.)

Pop culture historians and music scholars have long noted that the so-

The unforgettable 1962 release Fallout Shelter takes a more direct approach in conveying the fears of teenagers everywhere over nuclear annihilation. Its melodramatic storyline of a boy who wants to share his family’s shelter with his girlfriend and his father’s intervention is a perfect blending of elements from the overt and the allegorical/subtle Bomb song.

And with the tune’s lyrics about radiation sickness and fire-

However, Bobby Braddock, the songwriter and producer of Fallout Shelter, admitted in an interview that drugs may have exacerbated his World War III mania: “To be very candid, I was a musician going through serious psychological problems due to an overdose of speed at the time and I was quite paranoid; I had tried to talk my parents into having a fallout shelter built—I remember we went to a place that built them and looked at their model.”

A secondary, non-

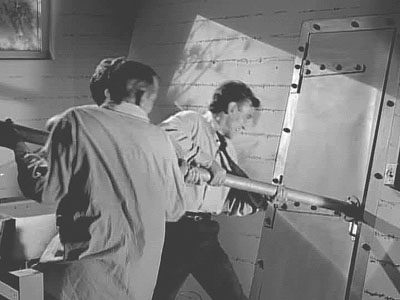

Not familiar with that classic T-

The Shelter

Season 3, episode 68, aired 9/29/61

It is a typical evening in a typical suburban community. At the residence of physician Bill Stockton, he enjoys a birthday party being thrown for him by his wife Grace and their son Paul. Also at the party are Jerry Harlowe, Bill’s brother-

As panic ensues, the doctor locks himself and his family into his shelter. The same gathering of friends becomes hysterical and now wants to occupy the shelter. All of the previous cordiality is now replaced with soaring desperation; pent-

Just then, a final Civil Defense broadcast announces that the objects have been identified as harmless satellites and that no danger is present. The neighbors apologize for their behavior; yet Stockton wonders if they have not destroyed each other – and themselves – without a bomb.

This theme of violence and shelters didn’t show up just in drama and popular music:

Following President John F. Kennedy’s Berlin crisis speech on July 25, 1961 that featured prominent and alarming references to nuclear war and civil defense, the topic of shelter morality entered the national discussion. Indeed, Time magazine published a remarkable article entitled “Gun Thy Neighbor” in its August 18, 1961 edition that reflected hard-

“When I get my shelter finished, I’m going to mount a machine gun at the hatch to keep neighbors out if the bomb falls. I’m deadly serious about this. If the stupid American public will not do what they have to to save themselves, I’m not going to run the risk of not being able to use the shelter I’ve taken the trouble to provide to save my own family.”

The Time article concludes with quotes from a gaggle of religious representatives (two Lutherans, an Episcopalian, a Methodist, a Catholic and a Baptist) opining on the morality of shelter defense. With one exception, pacifism was the standard line coming from these holy men.

However, a few weeks later, another holy man weighed in with an opposing viewpoint on the pages of the Jesuit magazine, America (National Catholic Weekly Review). In fact, Father L.C. McHugh’s opinion piece (“Ethics at the Shelter Doorway,” America, September 30, 1961) cites the Time article as his impetus for writing. Father McHugh took particular exception to the following quote in the Time story from the Reverend Hugh Saussy of the Holy Innocents Episcopal Church in Atlanta, Georgia: “If someone wanted to use the shelter, then you yourself should get out and let him use it. That’s not what would happen, but that’s the strict Christian application.”

Father McHugh belittles the moralist argument against defending one’s shelter in his piece and asserts that “unjust aggressors” should be “repelled by whatever means will effectively deter their assault.” Ironically, the editors of the magazine sought to soften the priest’s uncompromising position on shelter defense by offering this ridiculous and baseless line in the accompanying writer’s biography: “Our guess is that Fr. McHugh would be the first to step aside from his own shelter door, yielding space to his neighbor.”

Coincidentally, the night before the publication date of Father McHugh’s controversial article, the CBS television network broadcast the famous episode of The Twilight Zone written by Rod Serling entitled “The Shelter.” This harrowing story about a homeowner locking his frenzied neighbors out of his shelter after an announced UFO sighting crystallized the shelter debate better than a thousand dueling op-

Father McHugh’s article spurred the shelter debate further and various newspaper articles commented on his unlikely position. In a September 27, 1961 New York Times piece by John Wicklein the paper called upon Rabbi Herbert Brichto, a professor of the Bible at the Hebrew Union College’s Jewish Institute of Religion for an opinion the America magazine article. Rabbi Brichto responded that “…preparation for an atomic war, such as building fall-

And Time magazine re-

So well publicized was Father McHugh’s article that even Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy referenced the priest in an internal White House policy discussion on the issue of private versus public shelters. In Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.’s JFK administration memoir, A Thousand Days (Houghton Mifflin, 1965, page 749), RFK is quoted as saying in a forlorn voice, “There’s no problem here — we can just station Father McHugh with a machine gun at every shelter.” According to Schlesinger and other sources, it was during the McHugh-

A P.S. to the Braddock Fallout Shelter song story …

Braddock would soon abandon his Cold War obsessions and focused on producing more commercial fare. Indeed, he went on to become one of Nashville’s biggest hit makers (1968’s D-

For a less gloomy shelter song, check out this 1961 satirical one by Mike and Bernie Winters:

Fallout Shelter

I’m not scared

I’m prepared

We’ll be spared

I’ve got a fallout shelter, it’s 9 by 9

Hi-

But it’s party time in my radiation station

A 14 day supply of multi-

Build a bomb bungalow, one of your own

With no down payment and a government loan

Let the tests go on in the atmosphere

In my fallout shelter, I’ll have no fear

My baby and me, cozy we will be

Away from radioactivity

20 megatons is the size of the boom

And if they let it go, I’ll feel no doom

Let the cats run about, helter-

I’m not scared

I’m petrified

We’ll be spared

20 megatons is the size of the boom

And if they let it go, I’ll feel no doom

Let the cats run about, helter-

So if you want to be full of confidence

Get survival jazz and civil defense

You’ll live like a king in your fallout pad

‘Till the all clear sounds, we’re swingin’, dad

We’re swingin’, dad

So what?

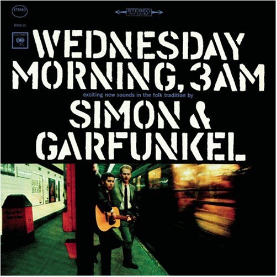

Next up, a relevant platter by the inimitable Simon and Garfunkel. (And no, the song isn’t “Sound of Silence.”)

“The Sun is Burning”

Singers: Simon and Garfunkel

Composer: Ian Campbell (“Ian Campbell Folk Group”)

Year: 1964, S&G first album, Wednesday Morning, 3 AM

On a Personal Note:

I was a 19 year old Sophomore at Michigan State University when the previously little-

None of the other songs on the album had been marketed as singles at that point, so it was a real pleasurable adventure to play through the collection. Side One included “The Sound of Silence” and five other very folk-

Go Tell It on the Mountain

And then Track #4 started. “The Sun is Burning.”

The sun is burning in the sky

Strands of clouds go slowly drifting by

In the park the lazy bees

Are droning in the flowers, among the trees

And the sun burns in the sky

It was a soothing and pretty ballad, with just a hint almost of a calypso beat. I was entranced. It was obviously going to be something sort of like the vintage Gershwin song “Summertime, and the livin’ is easy, fish are jumpin’, and the cotton is high…”

And then came verse 4. And my heart sank into my stomach! Have a listen to the whole thing..

The Sun Is Burning

The lyrics haunt me to this day!

From 1000 Songs Everyone Must Hear (Politics and Protest section) “The Sun is Burning”

The power of subtlety in protest music is brilliantly expressed by one of the earliest anti-

By the end, the song is echoing the published descriptions of the agonies suffered by the inhabitants of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the bombings in 1945.

The Sun is Burning

The sun is burning in the sky

Strands of clouds go slowly drifting by

In the park the lazy bees

Are droning in the flowers, among the trees

And the sun burns in the sky

Now the sun is in the West

Little kids go home to take their rest

And the couples in the park

Are holdin’ hands and waitin’ for the dark

And the sun is in the West

Now the sun is sinking low

Children playin’ know it’s time to go

High above a spot appears

A little blossom blooms and then draws near

And the sun is sinking low

Now the sun has come to Earth

Shrouded in a mushroom cloud of death

Death comes in a blinding flash

Of hellish heat and leaves a smear of ash

And the sun has come to Earth

Now the sun has disappeared

All is darkness, anger, pain and fear

Twisted, sightless wrecks of men

Go groping on their knees and cry in pain

And the sun has disappeared

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament is most famous today for its iconic symbol.

The CND Symbol

One of the most widely known symbols in the world, in Britain it is recognised as standing for nuclear disarmament – and in particular as the logo of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). In the United States and much of the rest of the world it is known more broadly as the peace symbol.

It was designed in 1958 by Gerald Holtom, a professional designer and artist and a graduate of the Royal College of Arts. He showed his preliminary sketches to a small group of people in the Peace News office in North London and to the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War, one of several smaller organisations that came together to set up CND.

Gerald Holtom, a conscientious objector who had worked on a farm in Norfolk during the Second World War, explained that the symbol incorporated the semaphore letters N(uclear) and D(isarmament).

He later wrote to Hugh Brock, editor of Peace News, explaining the genesis of his idea in greater, more personal depth:

“I was in despair. Deep despair. I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad. I formalised the drawing into a line and put a circle round it.”

The first badges were made by Eric Austin of Kensington CND using white clay with the symbol painted black. Again there was a conscious symbolism. They were distributed with a note explaining that in the event of a nuclear war, these fired pottery badges would be among the few human artifacts to survive the nuclear inferno.

These early ceramic badges can still be found and one, lent by CND, was included in the Imperial War Museum’s 1999/2000 exhibition From the Bomb to the Beatles.

Misrepresentation and misuse…

There have been claims that the symbol has older, occult or anti-

Although specifically designed for the anti-

This of course sometimes leads to its use, or misuse, in circumstances that CND and the peace movement find distasteful. It is also often exploited for commercial, advertising or generally fashion purposes. We can’t stop this happening and have no intention of copyrighting it. All we can do is to ask commercial users if they would like to make a donation. Any money received is used for CND’s peace education and information work.

On a personal note again, I think “The Sun Is Burning” hit me particularly hard in early 1966 because my husband, George, had just finished an “interpretive reading” class at college the previous semester. For his main project, he read to the class a section from John Hersey’s book Hiroshima. Hersey, a reporter for The New Yorker magazine, had traveled to Hiroshima within a year after the bomb had devastated the city and killed and maimed tens of thousands of people. He wove a description of the bombing and its aftermath around first-

As George was preparing to do his class reading, I picked up the book and read through it myself. It was the first time I had ever read any material that personalized the events of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Up to that point, they were in my mind just that … “events” that had a date and some data attached to them. Power of so many tons of TNT. So many buildings smashed, raw data on casualties. Names of the bomber pilots, nicknames of the planes and the bombs.

The “view” I had was just like that of the bomber crews … from high in the sky.

Hersey brought me down to the ground and face to face with human suffering. Indeed, there were vivid descriptions of “twisted, sightless wrecks of men” groping on their knees and crying in pain. To say nothing of women and children doing the same. I was particularly touched by the line in the song saying that the blinding flash and hellish heat had left a “smear of ash.” The ash, of course, being incinerated people near Ground Zero. Then again, when reading the descriptions of misery and later disfigurements and death from radiation poisoning, it would seem that in many cases the idea of instant incineration was more merciful.

Composer Ian Campbell had indeed succeeded in leaving an indelible impression with his understatement that subtly set up an idyllic scene … and then shocked his listeners with stark reality. Right after WWII that reality seemed SO far away from America, something that could only happen to alien races of people in distant lands. But by 1966 when I first heard this song, the Mutually Assured Destruction concept of the Cold War brought this reality agonizingly close to home.

But of course no one could keep focused on this all the time. Even though the specter of nuclear war lurked in the shadows all the time for people in the ‘50s and early 60s, obviously they thought about all sorts of other things in daily life, including the simple bobby-