Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8

Not So Fabulous Fifties, Part 3

Civil Defense, Shelters…and “Emotional Management”

After the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb in 1949, the American public was understandably nervous. They were aware of the destruction that individual atomic bombs did to the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But the general public did not know a lot yet about the dangers of radiation and fallout.

So, a new Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) was set up in 1951 to educate – and reassure – the country that there were ways to survive an atomic attack from the Soviet Union. They commissioned a university study on how to achieve “emotion management” during the early days of the Cold War.

The Civil Defense plans included two seemingly contradictory strategies:

It was first necessary to have an unusual level of openness about just how bad nuclear bombs were. At first, both President Eisenhower and others in his administration had hoped to keep information about nuclear weapons closely guarded. There had been an assumption that the Russians were mere bumpkins in the nuclear race, even after they showed, in 1949, they could develop an atomic bomb. It was assumed this was just the result of nuclear secrets leaked by WW 2 spies, and since those leaks had been discovered and plugged, the Russian nuclear program would dry up. But when the Russians successfully tested their first thermonuclear hydrogen bomb in 1953, it was painfully obvious that the US had underestimated the skill level of Russian scientists, and the threat they could pose to US supremacy.

If the US populace was to be induced to support the development of a growing US nuclear arsenal, they would need to be convinced that such an arsenal was absolutely necessary. Thus President Eisenhower established what he chose to call “Operation Candor.”

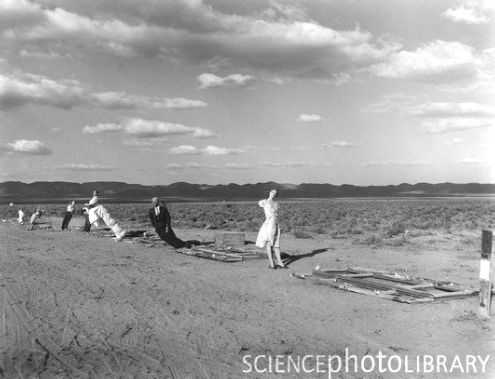

Ike and members of his administration issued speeches and articles going into great detail about the nuclear capabilities of the US and Russia and about the grim reality of the effects of atomic and hydrogen weapons. Above-

Below the following sample pictures are links to a short two-

The eerily cheerful lady reporter in this documentary below chattily comments on the effects of the blast on mannequins placed inside and outside the structures in what was dubbed “Survival Town.”

It’s not quite clear what the point of this test was … even the narrator admits that the bomb involved was an A-

But of course focusing only on all this “candor” would not have done much for keeping the masses of US citizens from developing utter paranoia and despair over the arms race! So it was necessary to add the second element to the Presidential Plan. The potential for paranoia and panic had to be controlled through a planned program of “emotion management.”

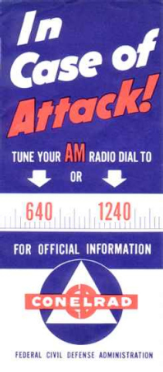

The earliest arm of this management program was the introduction of the Civil Defense Administration, and its adoption of the CONELRAD program.

Early in the “Cold War”, there was concern that enemy bombers could simply home in on American cities by tuning in to specific broadcast radio and television transmitters. At the time, certain 50 kilowatt AM broadcast stations were still clear channel, the only stations in the nation at night on specific frequencies.

The 1951 solution to the problem was called Conelrad which stood for CONtrol of ELectromagnetic RADiation. Conelrad was “devised to provide radio communications in a national emergency while denying enemy bombers the use of radio beams as an aid in finding targets. This is accomplished by having television and FM stations cease their regular transmissions and selected AM stations to go to either 640 or 1240 KHz.”

In an alert, with broadcast stations transmitting only on either 640 or 1240 KHz, no directional aid would be available to an enemy bomber. Emergency information for the public would be broadcast on those frequencies.

Radios beginning with model year 1953 are marked with little CD triangles at 640 and 1240 on the AM broadcast dial. The CD stood for Civil Defense or Conelrad.

Through most of the 1950s, the advice on “duck and cover,” although admitted privately by experts to be very unlikely to provide any real survival benefits in the event of an actual nuclear attack, was drummed into the heads of most school children across the country. The reason? It provided “emotion management.” It gave children and teens the illusion that there really was something tangible they could do to help themselves in a nuclear attack. And the continual practice sessions for ducking and covering gave them a focus for nervous emotional energy. Thus feelings of anxiety and panic would be minimized.

At first very little was done to help find “things to do” for adults in a similar vein. Although individual “family bomb shelters” were mentioned early on, few people in the early 1950s took the suggestion seriously. But once both the US and Russia had successfully tested thermonuclear H-

In a September letter published in Life magazine, Kennedy advised readers on survival tips. The article entitled “You Could Be Among the 97% to Survive If You Follow Advice in These Pages” was an unrealistic assessment of the likelihood of survival. Kennedy’s science advisers informed him that his analysis would provide false hope, but Kennedy insisted that as long as some were saved, it was worth it.

HE SAID…

“Today, every inhabitant of this planet must contemplate the day when this planet may no longer be inhabitable. Every man, woman, and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or madness. The weapons of war must be abolished before they abolish us.”

Despite the unlikely success of the program, Kennedy urged governors to take civil defense seriously and instructed the Pentagon to create a pamphlet discussing the steps to take for survival. In its draft form, its suggestions — just like Kennedy’s article — were unrealistic. Even more troubling, only the affluent were able to build fallout shelters, and newspapers reported on the buildup of weapons among New Jersey and California suburbanites who were preparing to fend off nearby city dwellers from using their shelters. [Source]

Kennedy gave a national speech on the same topic in October, and only weeks later it became obvious that he needed to be taken seriously.

On 10/30/61 the Russians tested the largest nuclear bomb ever exploded (including to this day!), a monster nicknamed Tsar Bomba. It exploded with 50 Megatons of force—and it could have released 100 megatons, but the Russians chose to “power down” the impact before detonating it.

In the shadow of such an apocalyptic weapon, it didn’t take long for shelter construction to become widespread.

When bomb shelters were all the rage

Civil defense officials talked confidently of group shelters for 50 million people, but in the new suburban communities the nervous were taking survival into their own hands. Bomb shelters costing from $100 to as much as $5,000 for an underground suite with phone and toilet were selling like hotcakes.

Wall Street investors said the bomb shelter business could gross up to $20 billion in the coming years (if there would be coming years).

Survival stores around the nation sold air blowers, filters, flashlights, fallout protection suits, first aid kits and water. General Foods and General Mills sold dry-

Families with well stocked shelters lived with the fear that after a nuclear attack they’d be invaded by an army of friends and neighbors who neglected to build bunkers of their own. Many ordered contractors to construct their shelters in the dead of night so nosey neighbors wouldn’t see. One owner assured his neighbor that the bomb shelter he was building was really a wine cellar.

Civil defense films assured the public that simple precautions like walled-

… Major airlines, Detroit automakers, IBM, the phone company and Wall Street planned employee shelters. The Federal Reserve designated banks for postwar check cashing, and a farmer in Iowa built a fallout shelter for 200 cows.

… A year later, the Cuban Missile Crisis would shove the world to the brink for 13 agonizing days. Newspaper headlines blared warnings of impending annihilation. “Highest Urgency, Kennedy Reports,” “Invasion Possible, Air, Sea and Ground Forces Ordered Out for Maneuvers,” they cried.

But the bomb never dropped.

The world heaved a sigh of relief as the Soviets backed off. And as the immediate peril of nuclear holocaust began to fade, Americans began to accept that fallout shelters probably did little to protect them from nuclear disaster. The backyard bomb shelters became wine cellars, fruit cellars, or just quietly filled up with water.

Government officials acknowledge that over the last several decades they have quietly been discarding nearly a half-

And it wasn’t just suburbanites who built shelters:

Even presidents had their secrets. After 1961 saw crises in Cuba, Berlin and the Soviet Union, President Kennedy recommended, “A fallout shelter for everybody, as rapidly as possible.” He had a fallout shelter built in seven days by U.S. Navy Seabees at his vacation home on Peanut Island, near Palm Beach. Although it was a well-

Treaties with the Soviet Union in the late 60s calmed down fears of Mutually Assured Destruction, the Detachment Hotel was abandoned, and in later years it became a favorite hangout for the homeless. More recently it has been refurbished and is now a museum.

Termed the Detachment Hotel in documents, the fallout shelter was built by Navy Seabees in less than two weeks. Deftly camouflaged by trees, it was hard to spot. If people asked, they would be told it was a munitions depot, nothing more. Kennedy visited the bunker twice during a drill.

“The government never declared it existed until 1974,” said Anthony Miller, a member of the executive board of the Palm Beach Maritime Museum, a nonprofit organization that leases part of the land on Peanut Island and gives tours of the bunker. “But it was the worst-

With the Soviets intent on shipping nuclear warheads to nearby Cuba, Kennedy was assured a radiation-

The bunker, which fell into disrepair in the 1990s, was cleaned up and has been open for tours since 1999.

The decor is fittingly rustic, a far cry from Jacqueline Kennedy’s sensibilities. There is room enough to hold 30 people on 15 metal bunk beds for 30 days, if not very comfortably.

Shelves are stocked with giant tins of waterless hand cleaner (today’s hand sanitizers), cans lined with lead that contained drinking water (no longer advisable), deodorant to clean clothes, petroleum jelly, castor oil and ample Army K-

In one corner, there is a rocking chair, a nod to Kennedy’s bad back.

Would all these fallout shelters have actually worked to save lives in significant numbers?

Experts can’t agree on how well these shelters would protect occupants from radiation but they can agree that there were other problems to worry about. Most shelters didn’t have sufficient air-

The craze for fallout shelters eventually faded, but before it did, one record company found a way to make some money off the paranoia:

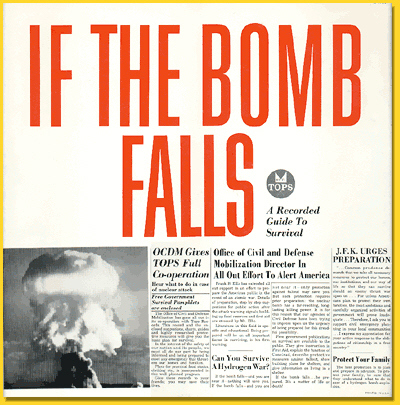

If the Bomb Falls: A Recorded Guide to Survival

[ 1961, TOPS Records ]

Released shortly after JFK’s Civil Defense appeal to America in the pages of LIFE magazine, this chilling spoken word LP was issued complete with a bonus insert manual on how to construct a “Family Fallout Shelter.”

SIDE ONE, “What to Do In Case of Nuclear Attack,” opens with a CONELRAD alert signal and is followed by the no-

SIDE TWO, “Supplies Needed for Survival,” offers a litany of items required to wait out World War III: “…cups, napkins, matches, pocket knife, battery-

And here’s where some of the “adult emotion management” came in. For this LP included the following advice:

By all means provide some tranquilizers to ease the strain and monotony of life in a shelter. A bottle of 100 should be adequate for a family of four. Tranquilizers are not a narcotic and are not habit forming. Ask a doctor for his recommendation.”

YUP ….REAL “emotion management”!! Angst was VERY real.

Although it seems the record company wasn’t quite clear on the concept … for they also added to the angst with some of the ominous wording on the LP.

Speaking of recordings such as this LP, there was a whole music genre that grew up in the 1950s and 60s that churned out songs—both gleeful and grim—with an Atomic Theme. We’ll take a look at it next.