Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8

Not So Fabulous Fifties, Part 2

MADmen

“I begin to believe in only one civilizing influence—

the discovery one of these days

of a destructive agent so terrible that War shall mean annihilation

and men’s fears will force them to keep the peace”.

English author Wilkie Collins,

writing at the time of the Franco-

It took only 75 years for Collins’ speculation to come to fruition.

And his comments are recognized as probably the earliest reference to the concept dubbed during the Cold War as “Mutual Assured Destruction.”

MAD

There was, of course, no mutuality in August 1945 when the US dropped the first … and only … two nuclear bombs ever used in an actual act of war. At the time it was the only nation with such capability. But this was not because it was the only nation that had been working on such “terrible” weapons. US leaders suspected from US spy efforts that they were in a frantic race with Germany to see whose scientists could unravel the mystery of “splitting the atom”… and use the knowledge first to build a “terrible destructive agent.”

There is little doubt that if the Germans would have managed to pull off such a coup, they would have brandished the weapon before the astonished eyes of the world, and the history of civilization would have been quite different than it has turned out to be in the 21st century.

Instead, the US really did “beat the Germans to the punch.” But the US never used the weapon on the German front of World War 2…Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, two months before the first Terrible Agent was tested and found ready for use.

US scientists began serious work on a nuclear bomb in 1941, just months before the US entered the war.

In August 1939, prominent physicists Leó Szilárd and Eugene Wigner drafted the Einstein–Szilárd letter, which warned of the potential development of “extremely powerful bombs of a new type”. It urged the United States to take steps to acquire stockpiles of uranium ore and accelerate the research of Enrico Fermi and others into nuclear chain reactions. They had it signed by Albert Einstein and delivered to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

(Einstein had added his own comments: “A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might well destroy the whole port with some of the surrounding territory. Letter from Albert Einstein to U.S. President Roosevelt in 1939)

Roosevelt called on Lyman Briggs of the National Bureau of Standards to head the Advisory Committee on Uranium to investigate the issues raised by the letter. Briggs held a meeting on 21 October 1939, which was attended by Szilárd, Wigner and Edward Teller. The committee reported back to Roosevelt in November that uranium “would provide a possible source of bombs with a destructiveness vastly greater than anything now known.”

Briggs proposed that the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) spend $167,000 on research into uranium, particularly the uranium-

This led directly to the establishment of what was dubbed the “Manhattan Project.”

At a meeting between President Roosevelt, Vannevar Bush and Vice President Henry A. Wallace on 9 October 1941, the President approved the atomic program. To control it, he created a Top Policy Group consisting of himself—although he never attended a meeting—Wallace, Bush, Conant, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George Marshall. Roosevelt chose the Army to run the project rather than the Navy, as the Army had the most experience with management of large-

Four years later, the scientists involved in the project had indeed created the prototype of “an extremely powerful bomb of a new type.” In an extremely powerful instance of understatement, those involved in the project nicknamed the creation “the gadget.”

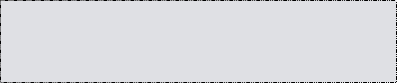

A test of The Gadget was arranged for July 16, 1945, in the desert about 35 miles southeast of Socorro, New Mexico, at the Alamogordo Test Range, in the Jornada del Muerto (Journey of the Dead Man) desert. (Now the White Sands Missile Range.) The code name for this test—in a powerful instance of irony—was “Trinity.” Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army Corps of Engineers, director of the Manhattan Project oversaw the test.

At 05:30 on 16 July 1945 the gadget exploded with an energy equivalent of around 20 kilotons [20,000 tons: 20KT] of TNT, leaving a crater of Trinitite (radioactive glass) in the desert 250 feet (76 m) wide. The shock wave was felt over 100 miles (160 km) away, and the mushroom cloud reached 7.5 miles (12.1 km) in height. It was heard as far away as El Paso, Texas, so Groves issued a cover story about an ammunition magazine explosion at Alamogordo Field.

The Genie was out of the bottle, and it would not be returned. You can experience a tiny bit of the real-

Confident that The Gadget worked satisfactorily, and with the end of the War with Japan not clearly in sight, the extremely controversial decision was made to use two similar gadgets on the (primarily) civilian population of two large cities in Japan.

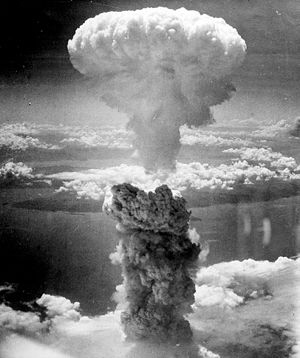

Less than a month after the Trinity test, an August 6, 1945, an Atomic Bomb code-

A rare color image, taken by a 16 mm movie camera aboard a B-

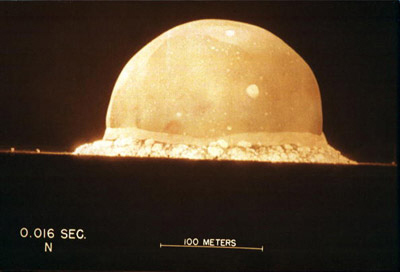

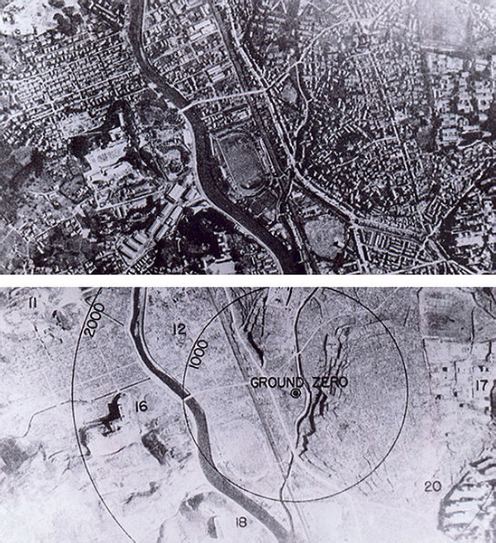

Before and after pictures of Hiroshima from the sky show the effects of Little Boy.

And from the ground it is even more obvious how little was left standing.

The plan was to detonate a second bomb, code-

Before and after photos of Nagasaki from the sky show the effects of Fat Man.

But the photos above only show primarily the damage to “man-

Within the first two to four months of the bombings, the acute effects killed 90,000–166,000 people in Hiroshima and 60,000–80,000 in Nagasaki, with roughly half of the deaths in each city occurring on the first day. The Hiroshima prefecture health department estimated that, of the people who died on the day of the explosion, 60% died from flash or flame burns, 30% from falling debris and 10% from other causes. During the following months, large numbers died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness.

Six days later, on August 15, the government of Japan announced its surrender to the Allies.

It was undisputed at this point that the US had the biggest, baddest weapons in the world.

But, as it turned out, this reputation didn’t last long. And the rival to fear in the Atomic Race was not Germany after all. It was a US Ally in WW2, the Soviet Union.

From the Wiki article on Mutual Assured Destruction:

In August 1945, the United States accepted the surrender of Japan after the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Four years later, on August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its own nuclear device. At the time, both sides lacked the means to effectively use nuclear devices against each other. However, with the development of aircraft like the Convair B-

From that point on, both nations entered an “arms race” that was much like kids playing “king of the hill.” Both kept making bigger and better bombs and testing them…sometimes secretly, sometimes with great fanfare.

And for a while it certainly wasn’t clear if Wilkie Collins’ theory, later dubbed “Mutual Assured Destruction,” would work …before the world WAS indeed annihilated.

The Edge of the Abyss

It shall be the policy of this Nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.

I call upon Chairman Khrushchev to halt and eliminate this clandestine, reckless and provocative threat to world peace and to stable relations between our two nations. I call upon him further to abandon this course of world domination, and to join in an historic effort to end the perilous arms race and to transform the history of man. He has an opportunity now to move the world back from the abyss of destruction—by returning to his government’s own words that it had no need to station missiles outside its own territory, and withdrawing these weapons from Cuba—by refraining from any action which will widen or deepen the present crisis–and then by participating in a search for peaceful and permanent solutions.

President John Kennedy, Television Address to the Nation regarding the “Cuban Missile Crisis,” Monday, October 22, 1962

“The Abyss of Destruction.”

Pretty strong words! The US had fought in WW1, according to President Woodrow Wilson, to “make the world safe for democracy.” But obviously that hadn’t worked.

So we’d fought WW2 to finish the job. And finish it we thought we did, with a display of power the likes of which the world had never seen. It must have seemed, to the average citizen, that after we dropped the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and brought the Japanese to their knees, SURELY the world was safe now. America would be the policeman of the world, as it was the nation with the Biggest Billy Club. In fact, the only nation with that Club.

So how did we manage to get from there in 1945 to the edge of the “Abyss of Destruction” a mere 17 years later?

From the Wikipedia entry, History of Nuclear Weapons

The Soviet Union was not invited to share in the new weapons developed by the United States and the other Allies. During the war, information had been pouring in from a number of volunteer spies involved with the Manhattan Project (known in Soviet cables under the code-

The Soviet spies in the U.S. project were all volunteers and none were Russians. One of the most valuable, Klaus Fuchs, was a German émigré theoretical physicist who had been a part in the early British nuclear efforts and had been part of the UK mission to Los Alamos during the war. Fuchs had been intimately involved in the development of the implosion weapon, and passed on detailed cross-

But once the war was over, the Russians hurried to begin making use of all of that Spy vs Spy information.

(Speaking of MADmen…the Spy vs Spy classic cartoon characters debuted in January 1961 in Mad Magazine—creator Antonio Prohias had only months earlier fled from his native Cuba under threat of arrest—or even execution—for his satirical parodies of the new Cuban dictator Fidel Castro.)

And the Russian scientists were quick learners.

Two days after the bombing of Nagasaki, the U.S. government released an official technical history of the Manhattan Project, authored by Princeton physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth, known colloquially as the Smyth Report. The sanitized summary of the wartime effort focused primarily on the production facilities and scale of investment, written in part to justify the wartime expenditure to the American public.

The Soviet program, under the suspicious watch of former NKVD [the Soviet Secret Police] chief Lavrenty Beria (a participant and victor in Stalin’s Great Purge of the 1930s), would use the Report as a blueprint, seeking to duplicate as much as possible the American effort. The “secret cities” used for the Soviet equivalents of Hanford and Oak Ridge literally vanished from the maps for decades to come.

And it only took them four years…some of it taken up with some bumbling of their efforts…for the Soviets to duplicate what was in the Report.

On August 29, 1949, the effort brought its results, when the USSR tested its first fission bomb, dubbed “Joe-

The loss of the American monopoly on nuclear weapons marked the first tit-

Joe-

In order to test the effects of the new weapon, workers constructed houses made of wood and bricks, along with a bridge, and a simulated metro [electric railway] in the vicinity of the test site. Armoured hardware and approximately 50 aircraft were also brought to the testing grounds, as well as over 1,500 animals to test the bomb’s effects on life.The resulting data showed the RDS explosion to be 50% more destructive than originally estimated by its engineers.

And the race was on.

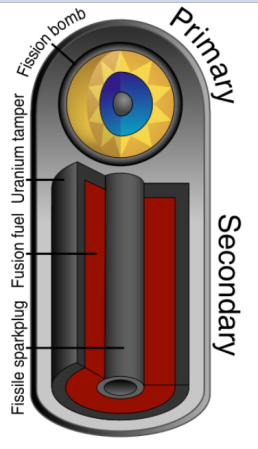

To clarify what happened next, it is necessary to understand the difference between “A-

The original atomic bomb used nuclear fission, in which big atoms (uranium or plutonium) were split into littler ones in a chain reaction, releasing vast amounts of energy.

The hydrogen bomb employs nuclear fusion, in which little atoms (various forms of hydrogen) fuse together to make bigger ones (helium), essentially the same process that occurs in the sun.

The only way to get enough heat to make this fusion process work … 50 million degrees… in a hydrogen bomb is to literally “ignite” it with a nuclear explosion—a fission bomb! So strangely enough, every H-

The basics of most thermonuclear weapons of the past and present: Radiation from a primary fission bomb compresses a secondary section containing both fission and fusion fuel. The compressed secondary is heated from within by a second fission explosion.

The bottom line of all this? Fission bombs are a million times more powerful than conventional chemical bombs. And fusion bombs are a thousand times more powerful than fission bombs.

And therein lies the race to the Abyss of Destruction.

The US took the first step three years after the Russians proved they could compete in the race. On November 1, 1952, the US tested its first thermonuclear/fusion device. It wasn’t really a weapon they planned to use… it was too big, at 20 feet tall and 140,000 pounds, for any plane to “deliver” it in warfare. It was just a prototype to test their thermonuclear theories.

So the bomb, code-

Its explosion yielded 10.4 megatons of energy—over 450 times the power of the bomb dropped onto Nagasaki— and obliterated Elugelab, leaving an underwater crater 6240 ft wide and 164 ft deep where the island had once been. Truman had initially tried to create a media blackout about the test—hoping it would not become an issue in the upcoming presidential election—but on January 7, 1953, Truman announced the development of the hydrogen bomb to the world as hints and speculations of it were already beginning to emerge in the press. [Source]

And the Race was on…

Not to be outdone, the Soviet Union exploded its first thermonuclear device, designed by the physicist Andrei Sakharov, on August 12, 1953, labeled “Joe-

And the race continued. Although both nations held many other tests, the next significant one was the US March 1, 1954, Castle Bravo test over the Bikini Atoll, also in the Marshall Islands.

The Bravo bomb yielded 15 MT of energy … and a lot of very bad publicity.

[The Castle Bravo test] became the worst radiological disaster in U.S. history. The combination of the unexpectedly large blast and poor weather conditions caused a cloud of radioactive nuclear fallout to contaminate over 7,000 square miles (18,000 km2), including Marshall Island natives and the crew of a Japanese fishing boat, as a snow-

The crew of the Japanese fishing boat, Lucky Dragon 5, returned to port suffering from radiation sickness and skin burns. Their cargo, many tons of contaminated fish, managed to enter into the market before the cause of their illness was determined. When a crew member died from the sickness and the full results of the contamination were made public by the U.S., Japanese concerns were reignited about the hazards of radiation and resulted in a boycott on eating fish (a main staple of the island country) for some weeks. [ibid]

The dropping of the two atomic bombs at the end of WW2 seemed very “justifiable” to most US citizens, and were no doubt more of a cause for pride in the present rather than fear for the future in the US at the time. But the Castle Bravo incident changed all that.

The hydrogen bomb age had a profound effect on the thoughts of nuclear war in the popular and military mind. With only fission bombs, nuclear war was something that possibly could be “limited.” Dropped by planes and only able to destroy the most built up areas of major cities, it was possible for many to look at fission bombs as a technological extension of large-

Even in the decades before fission weapons, there had been speculation about the possibility for human beings to end all life on the planet, either by accident or purposeful maliciousness—but technology had not provided the capacity for such action. The great power of hydrogen bombs made world-

The “Castle Bravo” incident itself raised a number of questions about the survivability of a nuclear war. Government scientists in both the U.S. and the USSR had insisted that fusion weapons, unlike fission weapons, were “cleaner,” as fusion reactions did not produce the dangerously radioactive by-

This fission stage made fusion weapons considerably more “dirty” than they were made out to be. This was evident in the towering cloud of deadly fallout that followed the Bravo test. When the Soviet Union tested its first megaton device in 1955, the possibility of a limited nuclear war seemed even more remote in the public and political mind. Even cities and countries that were not direct targets would suffer fallout contamination. Extremely harmful fission products would disperse via normal weather patterns and embed in soil and water around the planet.

Speculation began to run towards what fallout and dust from a full-

At some point late in his presidency, Dwight Eisenhower was pressured by some of his more hawkish advisors to approve development of some new sort of nuclear weapon that they were convinced would allow the US to “win” such a war. Eisenhower’s famous reply:

“You can’t have this kind of war. There just aren’t enough bulldozers to scrape the bodies off the streets.”

Alfred Nobel (yes, the one who set up the Nobel Prizes) was the inventor of dynamite in 1867. He had this to say about his invention:

“My dynamite will sooner lead to peace than a thousand world conventions. As soon as men will find that in one instant, whole armies can be utterly destroyed, they surely will abide by golden peace. ”

Sounds quite a bit like the sentiment of the earlier quote in this series from 1870 by Wilkie Collins, doesn’t it!

“I begin to believe in only one civilizing influence—the discovery one of these days of a destructive agent so terrible that War shall mean annihilation and men’s fears will force them to keep the peace”.

Nobel seemed to have thought he’d provided an agent destructive enough that people from then on would indeed “abide by golden peace.”

He was wrong.

Just how wrong? Keep reading.