Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8 Pt 9

Terrorism on American Soil, Part 7

Hidden in Plain Sight

In 1970, with the fiftieth anniversary of the horrific 1921 Tulsa Holocaust just one year away …

…Larry Silvey, the publications manager at the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce, decided that on the fiftieth anniversary of the riot, the chamber’s magazine should run a story on what had happened. Silvey then contacted Ed Wheeler, the host of ‘The Gilcrease Story,” a popular history program which aired on local radio. Wheeler — who, like Silvey, was white – agreed to research and write the article. Thus, during the winter of 1970-

Wheeler received anonymous threats related to his work on this article, but ignored them and finished it. Silvey began preparations to publish it in spring 1971, but once the management within the Chamber of Commerce realized just how pointed the article was going to be—including photographs never before published—they balked and killed the article. Silvey appealed to the board of directors, but they too nixed his plans.

Determined that his efforts should not have been in vain, Wheeler then tried to take his story to Tulsa’s two daily newspapers, but was rebuffed.

In the end, his article — called “Profile of a Race Riot” — was published in Impact Magazine, a new, black-

Don Ross was born in Tulsa in 1941. After high school he did a stint in the Air Force, and returned home to a job as a baker. He became involved in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and was at the 1963 “I have a dream” March on Washington. In the early 1970s he helped establish a regional magazine called Impact, modeled on Ebony magazine.

And when Ross published Wheeler’s article…

Ross was quoted in a Knight-

Ross continued a career and studies in Journalism, and eventually got a master’s degree in Political Science. In 1982 he won a seat in the Tulsa House of Representatives and served there for many terms. He helped push through various civil rights laws. And he led the fight to get the Confederate flag down from its spot flying above the legislature’s building. In 1989 Oklahoma became the first state to take that flag over its government buildings down.

And then there was his central role in bringing the history of the Tulsa Riot to state, national, and international attention:

Ross was the principal organizer of the 75th anniversary commemorations [1996] of the 1921 riot. The ceremony included the dedication of “The Wall Street Memorial,” a ten-

In 1997, Ross cosponsored legislation to establish the Tulsa Race Riot Commission. “Four years ago, if I had proposed a Tulsa Race Riot Commission, I would have been laughed off the House floor,” Ross commented in the newspaper Tulsa World at the time. “Even though the legislature is more conservative today, there are more people on all sides–including the governor and the mayor–who are pushing for this project and others that would benefit the citizens of north Tulsa [evidently STILL the area where most blacks are centralized in Tulsa, where Greenwood used to stand].” The Tulsa Race Riot Commission, an eleven-

Here is Don Ross, standing at the corner of Archer and Greenwood Streets in North Tulsa, in the heart of what used to be “Black Wallstreet”—before it was burned to the ground by rioters in 1921.

And that brings us to the details of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission’s work, which has been the source of most of the information in this Ground Zero series. That report was completed in 2001. Here is the preamble to that report:

The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Commission originated in 1997 with House Joint Resolution No. 1035. … and became law with Governor Frank Keating’s signature on April 6, 2000.

…The statute also charged the commission to produce …”a final report of its findings and recommendations” and to submit that report “in writing to the Governor, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, and the Mayor and each member of the City Council of the City of Tulsa, Oklahoma.” This is that report. It accounts for and completes the work of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Commission.

A series of papers accompanies the report. Some are written by scholars of national stature, others by experts of international acclaim. Each addresses at length and in depth issues of expressed legislative interest and matters of enormous public consequence. As a group, they comprise a uniquely special and a uniquely significant contribution that must be attached to this report and must be studied carefully along with it. [http://www.tulsareparations.org/FinalReport.htm ]

The history of the Tulsa Riot was shrouded in secrecy for so long, that there was considerable concern that the Commission not just do a cursory job, leaving much to continued speculation. If it was to be a document that would speak authoritatively on this event, which has national import as arguably the most vicious act of racial terrorism on American Soil in our history, it needed to be researched and written by scholars with impeccable credentials, with input and oversight by representatives of the Oklahoma government. It was.

…The governor was to appoint six members…Two state officials – the directors of the Oklahoma Human Rights Commission (OHRC) and of the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS) – also were to serve as ex officio members, either personally or through their designees.

[The Tulsa mayor] was to select the commission’s final three members. … One of the mayor’s appointees had to be “a survivor of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot incident”; two had to be current residents of the historic Greenwood community, the area once devastated by the “incident.”

… Governor Frank Keating’s six appointees included two legislators, each from a different chamber, each from an opposite party, each a former history teacher.

The Commission was also granted funds to hire a few expert consultants. The two main ones they chose who worked from a broad perspective were John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth.

… John Hope Franklin is the son of Greenwood attorney B. C. Franklin, a graduate of Tulsa’s Booker T. Washington High School (Fisk and Harvard, too), and James B. Duke Professor of History Emeritus at Duke University. Recipient of scores of academic and literary awards, not to mention more than a hundred honorary doctorates…

[Franklin recommended they include] Dr. Scott Ellsworth, a native Tulsan now living in Oregon…a Duke graduate who already had written a highly regarded study of the riot. [Ellsworth was the author of the extremely detailed description of the Riot that has been quoted throughout this series.]

In addition, they engaged the services of more focused researchers:

Legal scholars, archeologists, anthropologists, forensic specialists, geophysicists – all of these and more blessed this commission with technical expertise impossible to match and unimaginable otherwise. As a research group, they brought a breadth of vision and a depth of training that made Oklahoma’s commission a model of state inquiry.

The reason I take the time to include the information above, which may seem kind of pedantic, is this:

The Tulsa Holocaust was the subject of one of the most thorough, meticulous, scholarly studies done in recent times on a modern historical US event. The resulting reports leave no doubt about the heinous nature of this terrorist act aimed at a whole racial community (not aimed just at a few men with guns who were trying to protect a young man from a lynching!)

This event is not just an historical oddity, a unique situation that exploded “out of nowhere” and whose aftermath was irrelevant. The factors that led to it remain profoundly important in the Tulsa of today. And it was not an event that happened in isolation—it was just the worst of many such events that occurred over decades in the late 1800s and first half of the 20th century, in communities throughout the country. Events which I’m willing to bet most Americans are as unaware of as they have been of the Tulsa Holocaust.

Sample:

Wilmington [NC] Massacre of 1898

Originally labeled a race riot, it is now termed a coup d’etat, as white Democratic insurrectionists overthrew the legitimately elected local government, the only such event in United States history.

In the Wilmington Insurrection, two days after the election of a Fusionist white mayor and biracial city council, Democratic white supremacists illegally seized power from the elected government. More than 1500 white men participated in an attack on the black newspaper, burning down the building. They ran officials and community leaders out of the city, and killed many blacks in widespread attacks, but especially destroyed the [black] Brooklyn neighborhood. They took photographs of each other during the events. The Wilmington Light Infantry (WLI) and federal Naval Reserves, told to quell the riot, used rapid-

Armed crowd of white men posing among the ruins

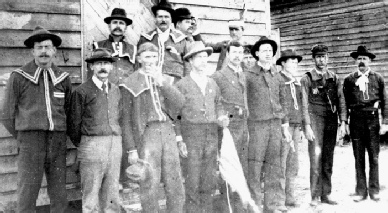

Destruction of the Manly printing press for the Wilmington Record on November 10, 1898. Destruction of the printing press was the first violent act by a mob of white supremacists. This newly discovered photograph provides more insight into the day’s activity and an up-

Group of Red Shirts, a white paramilitary group, posing at the polls.

And here is a first-

(What appears below is a rare eyewitness account provided by Rev. Charles S. Morris who became one of the refugees from the city. Morris provided the account in a speech in January 1899 before the International Association of Colored Clergymen meeting in Boston.)

Nine Negroes massacred outright; a score wounded and hunted like partridges on the mountain; one man, brave enough to fight against such odds would be hailed as a hero anywhere else, was given the privilege of running the gauntlet up a broad street, where he sank ankle deep in the sand, while crowds of men lined the sidewalks and riddled him with a pint of bullets as he ran bleeding past their doors; another Negro shot twenty times in the back as he scrambled empty handed over a fence; thousands of women and children fleeing in terror from their humble homes in the darkness of the night, out under a gray and angry sky, from which falls a cold and bone chilling rain, out to the dark and tangled ooze of the swamp amid the crawling things of night, fearing to light a fire, startled at every footstep, cowering, shivering, shuddering, trembling, praying in gloom and terror: half clad and barefooted mothers, with their babies wrapped only in a shawl, whimpering with cold and hunger at their icy breasts, crouched in terror from the vengeance of those who, in the name of civilization, and with the benediction of the ministers of the Prince of Peace, inaugurated the reformation of the city of Wilmington the day after the election by driving out one set of white office holders and filling their places with another set of white office holders—the one being Republican and the other Democrat.

All this happened, not in Turkey, nor in Russia, nor in Spain, not in the gardens of Nero, nor in the dungeons of Torquemada, but within three hundred miles of the White House, in the best State in the South, within a year of the twentieth century, while the nation was on its knees thanking God for having enabled it to break the Spanish yoke from the neck of Cuba. This is our civilization. This is Cuba’s kindergarten of ethics and good government. This is Protestant religion in the United States, that is planning a wholesale missionary crusade against Catholic Cuba. This is the golden rule as interpreted by the white pulpit of Wilmington. [Source]

Or how about a few years later in East St. Louis, Illinois:

The East St. Louis Riot (May and July 1917) was an outbreak of labor-

In the East St Louis Riot over 300 homes and buildings were destroyed, 6000 blacks left homeless, many dead or injured.

And two years later there was the Chicago Riot:

The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 was a major racial conflict that began in Chicago, Illinois on July 27, 1919 and ended on August 3.During the riot, dozens died and hundreds were injured. It is considered the worst of the approximately 25 riots during the Red Summer, so named because of the violence and fatalities across the nation. The combination of prolonged [white on black] arson, looting and murder was the worst race rioting in the history of Illinois. [Source]

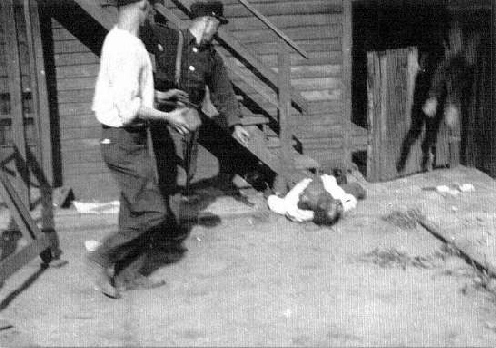

A white gang looking for African Americans during the Chicago Race Riot of 1919.

Black Victim Stoned to Death, Chicago Race Riots, July 1919

A group of white men and boys standing on the sidewalk in front of a house vandalized in the race riots of July-

Yes, the Tulsa Holocaust was by no means unique, just more wide-

The lessons the Tulsa event offers are relevant to the whole United States of America, of both the present and the future.

As the Commission’s final report noted:

Many have questioned why or even if anyone would be interested now in events that happened in one city, one time, one day, long ago. What business did today’s state lawmakers have in something so old, so local, and so deservedly forgotten? Surely no one cares, not anymore.

An answer comes from hundreds and hundreds of voices. They tell us that what happened in 1921 in Tulsa is as alive today as it was back then. What happened in Tulsa stays as important and remains as unresolved today as in 1921. What happened there still exerts its power over people who never lived in Tulsa at all.

How else can one explain the thousands of hours volunteered by hundreds of people, all to get this story told and get it told right? How else can one explain the regional, national, even international attention that has been concentrated on a few short hours of a mid-

Eventually it became largely unknown. So hushed was mention of the subject that many pronounced it the final victim of a conspiracy, this a conspiracy of silence.

That silence is shattered, utterly and permanently shattered. What ever else this commission has achieved or will achieve, it already has made that possible. Regional, national, and international media made it certain. The Dallas Morning News, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, National Public Radio (NPR), every American broadcast television network, cable outlets delivering Cinemax and the History Channel to North America, the British Broadcasting Corporation – this merely begins the attention that the media focused upon this commission and its inquiry. Many approached it in depth (NPR twice has made it the featured daily broadcast). Most returned to it repeatedly (the New York Times had carried at least ten articles as of February 2000). All considered it vital public information.

…Here is the point: The 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Commission is pleased to report that this past tragedy has been extensively aired, that it is now remembered, and that it will never again be unknown.

What I find profoundly sad is that, in spite of that flurry of media attention during a brief period around the year 2000, I personally STILL never heard of the event until stumbling across information about it when looking up a related topic a couple of years ago. Nor had any of my friends whom I have asked about it ever heard about it. They are all educated people, some of them avid history fans. They watch the history channel. Some tune in NPR.

So the reality is, although the information is now “out there in plain sight” all over the Internet IF you know where to look…I’m pretty sure the vast majority of the populace still are utterly unaware. Not unaware of just this single event, but of the whole sickening, wide-

How can this be? I have a theory to answer that question. You can read about it in the next section of this series.