Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8 Pt 9

Terrorism on American Soil, Part 1

Ground Zero

The Oxford English Dictionary, citing the use of the term in a 1946 New York Times report on the destroyed city of Hiroshima, defines ground zero as “that part of the ground situated immediately under an exploding bomb, especially an atomic one.” [Wiki]

Yes, the term Ground Zero was originally invented in connection with the development of the atomic bomb, designating the spot on the desert in New Mexico where the first bomb was detonated in 1945. Shortly after that it designated the targets of the first—and so far only—nuclear bombs used in warfare, strategic points in the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The area at and immediately around Ground Zero is where you expect virtually total destruction of human life and man-

Sometimes remnants of buildings and humans may be left on the outskirts of Ground Zero in the aftermath, as seen in these pictures of Nagasaki.

Since that time, the term Ground Zero has been expanded to metaphorically include the center of devastation of other types of situations involving disasters, whether the Twin Towers of 9/11 or the epicenter of major earthquakes.

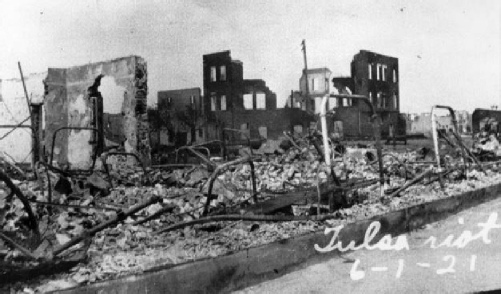

Here are some photos that are eerily similar to those of the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Can you guess where and when they were taken?

Since they are black and white, you might guess they are vistas of bombing targets somewhere in Europe or Asia during WW2, or in North or South Korea during the Korean War.

No, they don’t show the aftermath of international warfare of any kind. They depict the aftermath of a major disaster in the USA, the utter destruction of a whole community where 10,000 people lived.

But no, these are not photos of the aftermath of a natural disaster such as an earthquake or wildfire or a tornado.

These are photos from the virtually total destruction by fire of an African American community, an area called Greenwood, in North Tulsa, Oklahoma. No, not a fire started by a natural gas explosion. Not a fire that just “spread” from some “accident.”

The destruction by fire was at the hands of a roaring mob of thousands of white citizens from Tulsa “proper” to the south. During an 18-

It is considered by knowledgeable historians to be the most hideous incident of its kind in American history.

What… you say you never heard of it?

I hadn’t until a couple of years ago myself. Neither have most people. Including, up until about the year 2000, most of the citizens of Oklahoma and of Tulsa who were born after the event occurred.

Because it seems to have led to the most serious incidence of Mass Amnesia in American history. Willful amnesia.

The story starts in “Metropolitan Tulsa”…

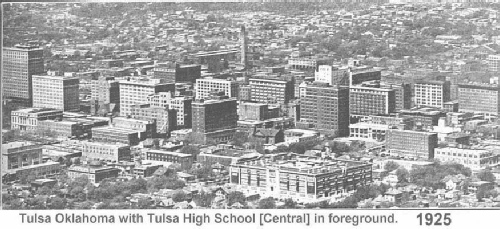

By 1910, thanks to the forest of derricks which had risen up over the nearby oil fields, Tulsa had mushroomed into a raucous boomtown of more than 10,000. Astonishingly, its real growth was only beginning. As the word began to spread about Tulsa — as a place where fortunes could be made, lives could be rebuilt, and a fresh start could be had — people literally began to pour in from all over the country. Remarkably enough, by 1920, the population of greater Tulsa had skyrocketed to more than 100,000.

Despite its youth, Tulsa also had acquired, by 1921, practically all of the trappings of older, more established American cities. Four different railroads — the Frisco, the Santa Fe, the Katy, and the Midland Valley — served the city, as did two separate inter-

A new city hall had been built in 1917, a new federal building in 1915, and a new county courthouse in 1912. New schools and parks also had been dedicated, and in 1914, the city erected a magnificent new auditorium, the 3,500 seat Convention Hall. Tulsa had grown so quickly, in fact, that even the old city cemetery had to be closed to new burials. In its place, the city had designated Oaklawn Cemetery, located at Eleventh Street and Peoria Avenue, as the new city cemetery. [SOURCE]

Yes, Tulsa was a thriving, modern city increasingly connected to the rest of the world:

In 1921, Tulsa could lay claim to two daily newspapers the Tulsa World, a morning paper, and a newly renamed afternoon daily, the Tulsa Tribune plus a handful of weeklies. Radio had not arrived yet, but the city was connected to the larger world through four different telegraph companies. Telephone service also existed — with some ten-

And what with this being well before the Great Depression, there was a lot of prosperity to go around, a lot of goodies to buy, a lot of places to spend your money.

… Frequently awash in money, the citizens of Tulsa had plenty of places to spend it from furniture stores, jewelry shops, and clothing stores to restaurants and cafes, motion picture theaters, billiard halls, and speakeasies. Those who could afford it could find just about anything in Tulsa, from the latest in fashion to the most modern home appliances, including vacuum cleaners, electric washing machines and Victrolas. For those whose luck had run dry, the city had its share of pawnshops and second-

This wasn’t some backwater shabby “Okie” town with people living in shacks either!

Many Tulsans were especially proud of the city’s residential neighborhoods — and with good reason. From the workingman’s castles that offered electric lighting, indoor plumbing, and spacious front porches, to the real castles that were being built by the oil barons, the city could boast of block after block of handsome, modern homes. While Tulsa was by no means without its dreary rooming houses and poverty stricken side streets, brand new neighborhoods with names like Maple Ridge, Sunset Park, Glen Acres, College Addition, Gurley Hill, and Irving Heights were built year after year. Some of the new homes were so palatial that they were regularly featured on picture postcards, chamber of commerce pamphlets, and other publications extolling the virtues of life in Tulsa.

Like this lovely home from 1920.

So too, not surprisingly, was downtown. With its modern office buildings, its graceful stone churches, and its busy nightlife, it is easy to see why Tulsans — particularly those who worked, played, or worshiped downtown — were so proud of the city’s ever-

What the pamphlets and the picture postcards did not reveal was that, despite its impressive new architecture and its increasingly urbane affectations, Tulsa was a deeply troubled town. As 1920 turned into 1921, the city would soon face a crossroads that, in the end, would change it forever.

There was, however, more to the story than the booming city:

However, chamber of commerce pamphlets and the picture postcards did not reveal everything. Tulsa was, in some ways, not one city but two. Practically in the shadow of downtown, there sat a community that was no less remarkable than Tulsa itself. Some whites disparagingly referred to it as “Little Africa”, or worse, but it has become known in later years simply as Greenwood. In the early months of 1921, it was the home of nearly ten-

… most of Tulsa’s African American residents had come to Oklahoma, like their white neighbors, in the great boom years just before and after statehood [Oklahoma became a state in 1907.] Some had come from Mississippi, some from Missouri, and others had journeyed all the way from Georgia. For many, Oklahoma represented not only a chance to escape the harsher racial realities of life in the former states of the Old South, but was literally a land of hope, a place worth sacrificing for, a place to start anew. And come they did, in wagons and on horseback, by train and on foot….

As of May 30, 1921, here is what Greenwood was like:

The southern end of Greenwood Avenue, and adjacent side streets, was the home of the African American commercial district. Nicknamed “Deep Greenwood”, this several block stretch of handsome one, two, and three-

Here’s how Deep Greenwood looked on May 30, 1921. Look close … it will never look like this again. Because two days later it will be in ruins. Along with over 1,200 homes in nearby neighborhoods.

But I digress. Back to May 30.

There were plenty of places to eat including late night sandwich shops and barbecue joints to Doc’s Beanery and Hamburger Kelly’s place. Lilly Johnson’s Liberty Cafe, recalled Mabel Little, who owned a beauty shop in Greenwood at the time of the riot, served home-

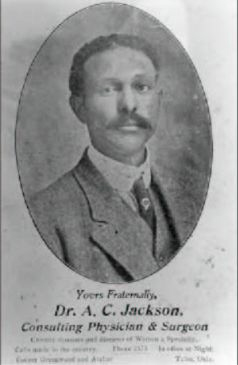

For a community of its size, the Greenwood business district could boast of a number of impressive commercial structures. John and Loula Williams, who owned the three-

Here’s a picture of how Dr. Jackson would have looked on May 30, 1921. Look close. Two days later, the “most able Negro surgeon in America” would be dead. In the yard of his own home, shot in the stomach as he held his arms up to attempt to “surrender” to members of the roaring mob.

But I digress again. Let’s learn a little more about Greenwood prior to May 31, 1921.

The overall intellectual life of Greenwood was, for a community of its size, quite striking. There was not one black newspaper but two – the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun. African Americans were discouraged from utilizing the new Carnegie library downtown, but a smaller, all-

…When it came to religious activity, however, there was no question at all where Tulsa’s African American community stood. Church membership in Tulsa ran high. On a per capita basis, there were more churches in black Tulsa than there were in the city’s white community as well as a number of Bible study groups, Christian youth organizations, and chapters of national religious societies. All told, there were more than a dozen African American churches in Tulsa … including First Baptist, Vernon A.M.E., Brown’s Chapel, Morning Star, Bethel Seventh Day Adventist, and Paradise Baptist, as well as Church of God, Nazarene, and Church of God in Christ congregations. Most impressive from an architectural standpoint, perhaps, was the beautiful, brand new home of Mt. Zion Baptist Church, which was dedicated on April 10, 1921 …

Yes, Greenwood was considered to have some of the finest black-

All in all, Greenwood was such a shining example of black entrepreneurship that it was dubbed by many “Black Wall Street.” And many blacks coming to settle there used the term “Promised Land” to describe their destination.

So there they were in their Promised land on May 30, 1921. Enjoying all the freedoms granted by the Constitution of the US (including its fourteenth amendment granting them citizenship), enjoying the inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. In a Christian nation, living next to a community of white people, most of whom no doubt considered themselves fine Christian folk—and likely went to church most Sundays.

And then IT happened.

…what is believed to be the worst case of racial violence in United States history. Within a span of 18 hours an entire Black neighborhood—more than 40 square blocks of manicured yards, precious heirlooms, treasured toys, stored memories, Black legacy and racial pride—had been eviscerated, leaving nearly 9,000 people homeless. Black Wall Street, that symbol of African-

“For some, what occurred in Tulsa on May 31 and June 1, 1921 was a massacre, a pogrom, or, to use a more modern term, an ethnic cleansing. [Source]

And from the looks of notes scrawled on the infamous “picture postcards” of the time, it seems some folks considered that a positive thing. Yeah, as the brilliant author of the message on this postcard put it, they were just “Runing the Negro out of Tulsa.”

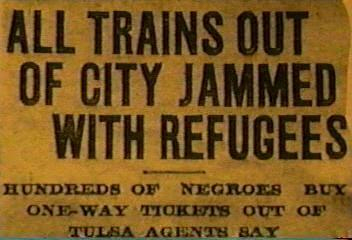

Many blacks lived in tents pitched in the ruins of the neighborhoods for the next year or more. As you can imagine, many fled the area.

Yes, this Ground Zero was on American soil in the proudly patriotic state of Oklahoma, long before the infamous bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, that is such a part of our national consciousness now.

So just what happened at Ground Zero, the community of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on those two infamous days? And why did I, as a certified school teacher with a university education, know nothing about it? In fact…

…the riot was discussed so little, and for so long, even in Tulsa, that in 1996, Tulsa County District Attorney Bill LaFortune could tell a reporter, “I was born and raised here, and I had never heard of the riot.”[SOURCE]

Americans USUALLY are absolutely obsessed about memorializing just about every event in our history. Witness all the “historical plaques” installed all over the place, at highway rest stops, downtown street corners, in front of important buildings.

For pity’s sake—in the last little town I lived in, Cedartown, Georgia, there is a plaque marking the birthplace of the man who voiced Winnie the Pooh in the Disney movies, Sterling Holloway! If the birth of some movie character actor is considered a big enough deal to put up a plaque—and name a street there after him—and similar minor bits of trivia are memorialized all over the nation, how did the Tulsa incident get virtually lost from our corporate popular history so soon after the fact, and for the next 80 years?

We’ll consider the answers to that question in the rest of this series.