Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

Meet MythAmerica Series

The American Way of Business, Part 3:

Plausible Deniability

A tragic event made the headlines in December 2012, as reported in this NY Times article:

New York Times, 12/6/2012

…ASHULIA, Bangladesh — The fire alarm shattered the monotony of the Tazreen Fashions factory. Hundreds of seamstresses looked up from their machines, startled. On the third floor, Shima Akhter Pakhi had been stitching hoods onto fleece jackets. Now she ran to a staircase.

But two managers were blocking the way. Ignore the alarm, they ordered. It was just a test. Back to work. A few women laughed nervously. Ms. Pakhi and other workers returned to their sewing tables. She could stitch a hood to a jacket in about 90 seconds. She arranged the fabric under her machine. Ninety seconds. Again. Ninety more seconds. She sewed six pieces, maybe seven.

Then she looked up.

Smoke was filtering up through the three staircases. Screams rose from below. The two managers had vanished. Power suddenly went out throughout the eight-

“We all panicked,” Ms. Pakhi said. “It spread so quickly. And there was no electricity. It was totally dark.”

The fire started about 7 PM, and it took area firefighters until almost noon the next day to finally extinguish it.

By then at least 112 people had been found dead and scores more were in hospitals being treated for burns and smoke inhalation.

Though most workers had left for the day when the fire started, the industry official said, as many as 600 workers were still inside working overtime.

The factory, which opened in May 2010, employed about 1,500 workers and had sales of $35 million a year, according to a document on the company’s Web site. It made T-

Most of the workers who died were on the first and second floors, fire officials said, and were killed because there were not enough exits.

The fire started on the first floor, probably in cluttered piles of yarn and fabric stored near electrical generators, instead of inside fireproof storage rooms as the (seldom obeyed) law required. Narrow exits on that floor became quickly blocked by panicking workers, and for those on upper floors—all three staircases leading down led through the ground floor. If they tried to descend, they were pushed back by smoke and deadly fumes.

There were no fire escapes—69 people were found dead on the second floor, and a dozen jumped to their deaths from windows on upper floors.

When the November fire broke out, [survivor Sumi] Abedin was working on the factory’s fourth floor. When a co-

A few workers forced open a window, and Abedin jumped out. “I jumped not to save my life,” she said. “I jumped to save my body. Because if I would be in the factory, my parents would not be able to get my body. I would be burned to death. So I jumped so at least they could find my body outside.”

Abedin said she woke up outside with a broken leg and a broken arm. When she turned to help the co-

Abedin was correct in her concern. Many bodies from inside the building could not be identified.

As you can guess, this factory was not making sari dresses for Indian shoppers. It was part of the global supply chain that feeds western megastores such as Walmart and Sears.

Yet Tazreen was making clothing destined for some of the world’s top retailers. On the third floor, where firefighters later recovered 69 bodies, Ms. Pakhi was stitching sweater jackets for C&A, a European chain. On the fifth floor, workers were making Faded Glory shorts for Walmart. Ten bodies were recovered there. On the sixth floor, a man named Hashinur Rahman put down his work making True Desire lingerie for Sears and eventually helped save scores of others. Inside one factory office, labor activists found order forms and drawings for a licensee of the United States Marine Corps that makes commercial apparel with the Marines’ logo.

… Amid the blackened tables and melted sewing machines…an Associated Press reporter discovered clothes and account books Wednesday that indicated the factory was used by a host of U.S. and European retailers.

Among the items discovered: children’s shorts with Wal-

And American “Dickies.”

If you were aware of this story, you may have read some of the editorial commentary that questioned what, if any, legal—or moral—liability these businesses had in regard to this tragedy. For of course, this was not some isolated situation. Bangladesh is notorious for a lack of oversight of the safety and rights of sweat shop workers in the thousands of factories that hire millions of workers in this poverty-

Nobody worries about the welfare of the workers, as they are merely cogs in a giant machine.

Bangladesh is now a garment manufacturing giant, the world’s second-

Starvation wages for work in hellish conditions—all in the name of making sure we can buy a Sponge Bob T-

Yes, Walmart and other retail giants have addicted us to prices that can only be kept “that low” by importing goods manufactured in places like Bangladesh.

“We as consumers like to be able to buy ever-

Well, actually there is a way that Walmart and the others could keep their prices low and still sell American made goods produced by workers making at least minimum US wages. They could reduce their corporate profits (and their executive salaries) by some small percent. But see, that wouldn’t be The American Way. After all, “the profit motive” has long been recognized as the fuel that was necessary to propel America to its one-

Of course, buying goods from sweat shops where people are burned alive isn’t very good for corporate Public Relations. Which might affect those corporate profits. So the Bangladesh fire was indeed a PR nightmare for Walmart and the others for a while.

After the fire, Walmart, Sears and other retailers made the same startling admission: They say they did not know that Tazreen Fashions was making their clothing.

But who, then, is ultimately responsible when things go so wrong?

The global apparel industry aspires to operate with accountability that extends from distant factories to retail stores. Big brands demand that factories be inspected by accredited auditing firms so that the brands can control quality and understand how, where and by whom their goods are made. If a factory does not pass muster, it is not supposed to get orders from Western customers.

Tazreen Fashions was one of many clothing factories that exist on the margins of this system. Factory bosses had been faulted for violations during inspections conducted on behalf of Walmart and at the behest of the Business Social Compliance Initiative, a European organization.

Yet Tazreen Fashions received orders anyway, slipping through the gaps in the system by delivering the low costs and quick turnarounds that buyers — and consumers — demand. C&A, the European retailer, has confirmed ordering 220,000 sweaters from the factory. But much of the factory’s business came through opaque networks of subcontracts with suppliers or local buying houses. Labor activists, combing the site of the disaster, found labels, order forms, design drawings and articles of clothing from many global brands.

Walmart and Sears have since said they fired the suppliers that subcontracted work to Tazreen Fashions. Yet some critics have questioned how a company like Walmart, one of the two biggest buyers in Bangladesh and renowned for its sophisticated global supply system, could have been unaware of the connection.

But of course, the name of the game is Plausible Deniability. “Tsk, tsk! We didn’t know! We would have been aghast if we did!” Yeah. Right.

…David Hasanat, the chairman of the Viyellatex Group, one of the country’s most highly regarded garment manufacturers, pointed out that global apparel retailers often depend on hundreds of factories to fill orders. Given the scale of work, retailers frequently place orders through suppliers and other middlemen who, in turn, steer work to factories that deliver low costs — a practice he said is hardly unknown to Western retailers and clothing brands. The order for Walmart’s Faded Glory shorts, documents show, was subcontracted from Simco Bangladesh Ltd., a local garment maker. “It is an open secret to allow factories to do that,” Mr. Hasanat said. “End of the day, for them it is the price that matters.”

But when the New York Times reporter comes calling, the Escape Clause can be pulled out of the hat. “We had no idea!...”

Tazreen Fashions is part of a larger garment conglomerate, the Tuba Group, which owns at least half a dozen apparel factories in Bangladesh. Mr. Hossain [Tazreen owner] said a team from Walmart’s local office conducted a compliance audit last year and faulted the factory for excessive overtime, while making no mention of fire safety or other issues. Moreover, he said, the local buying houses had also inspected and approved the factory, tantamount, he assumed, to approval from Walmart and the other global brands these middlemen represented.

Kevin Gardner, a Walmart spokesman, said the company stopped authorizing production at Tazreen “many months before the fire.” But he did not say why.

But of course no one was surprised several months later when Walmart and Sears “avoided even the appearance” of having the slightest connection to “the problem.”

On 15 May 2013, companies whose clothing was manufactured at the Tazreen Design Ltd. factory met in Geneva to discuss compensation payments for the victims of the fire; Walmart and Sears declined to send representatives to the meeting. [Wiki]

Why do I bring all this up in the context of American History? After all, can’t we expect such lack of respect for human life, such carelessness for others, in third world countries like Bangladesh, which don’t live by The American Way? For after all, isn’t The American Way the “Christian” Way? Hasn’t the American Way of Life and doing business always been based on “Biblical Principles”? (Bangladesh is about 90% Islamic, 10% Hindu.)

Maybe in recent decades the modern Walmart corporation and other big American businesses have fallen away from those ideals and become corrupt and greedy. But surely historically The American Way has been greatly superior to the horrid conditions in darkened Bangladesh. Hellish events such as the Tazreen fire and the one described below are tragic, but understandable in uncivilized nations.

The fire caused the deaths of 146 garment workers, who died from the fire, smoke inhalation, or falling or jumping to their deaths. Most of the victims were … aged sixteen to twenty-

Because the managers had locked the doors to the stairwells and exits – a common practice … to prevent pilferage and unauthorized breaks – many of the workers who could not escape the burning building jumped from the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors to the streets below.

Oh. Wait. That description isn’t from far-

I submit for your consideration a brief overview of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire:

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City on March 25, 1911, was one of the deadliest industrial disasters in the history of the city of New York and resulted in the fourth highest loss of life from an industrial accident in U.S. history. It was also one of the deadliest disasters that occurred in New York City – after the burning of the General Slocum on June 15, 1904 [over 1,000 people on their way to a German Lutheran church picnic died when that excursion steamship caught fire and sank in the East River] – until the destruction of the World Trade Center 90 years later.

The fire caused the deaths of 146 garment workers, who died from the fire, smoke inhalation, or falling or jumping to their deaths. Most of the victims were recent Jewish and Italian immigrant women aged sixteen to twenty-

Because the managers had locked the doors to the stairwells and exits – a common practice at the time to prevent pilferage and unauthorized breaks – many of the workers who could not escape the burning building jumped from the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors to the streets below.

… Under the ownership of Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, the factory produced women’s blouses, known as “shirtwaists.” The factory normally employed about 500 workers, mostly young immigrant women, who worked nine hours a day on weekdays plus seven hours on Saturdays, earning between $7 and $12 a week.

As the workday was ending on the afternoon of Saturday, March 25, 1911, a fire flared up at approximately 4:40 PM in a scrap bin under one of the cutter’s tables at the northeast corner of the eighth floor. The first fire alarm was sent at 4:45 PM by a passerby on Washington Place who saw smoke coming from the eighth floor. Both owners of the factory were in attendance and had invited their children to the factory on that afternoon.

The Fire Marshal concluded that the likely cause of the fire was the disposal of an unextinguished match or cigarette butt in the scrap bin, which held two months’ worth of accumulated cuttings by the time of the fire. Beneath the table in the wooden bin were hundreds of pounds of scraps which were left over from the several thousand shirtwaist that had been cut at that table. …

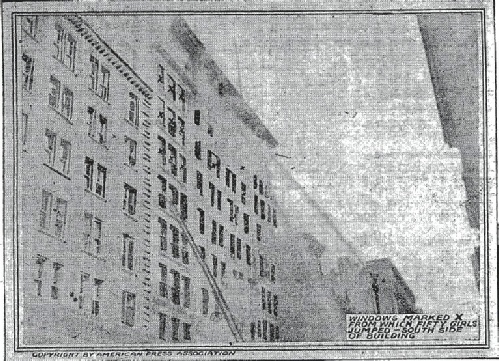

The building’s south side, with windows marked X from which fifty women jumped

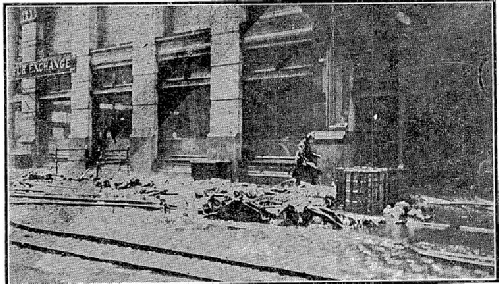

The building’s east side, with 40 bodies on the sidewalk. Two of the victims were found alive an hour after the photo was taken.

A bookkeeper on the eighth floor was able to warn employees on the tenth floor via telephone, but there was no audible alarm and no way to contact staff on the ninth floor. According to survivor Yetta Lubitz, the first warning of the fire on the ninth floor arrived at the same time as the fire itself. Although the floor had a number of exits, including two freight elevators, a fire escape, and stairways down to Greene Street and Washington Place, flames prevented workers from descending the Greene Street stairway, and the door to the Washington Place stairway was locked to prevent theft by the workers; the locked doors allowed managers to check the women’s purses. The foreman who held the stairway door key had already escaped by another route. Dozens of employees escaped the fire by going up the Greene Street stairway to the roof. Other survivors were able to jam themselves into the elevators while they continued to operate.

Within three minutes, the Greene Street stairway became unusable in both directions. Terrified employees crowded onto the single exterior fire escape, which city officials had allowed Asch to erect instead of the required third staircase. It was a flimsy and poorly anchored iron structure which may have been broken before the fire. It soon twisted and collapsed from the heat and overload, spilling about 20 victims nearly 100 feet (30 m) to their deaths on the concrete pavement below.

Just as in the 9/11 Twin Towers inferno, there were heroes of the story that day…

Elevator operators Joseph Zito and Gaspar Mortillalo saved many lives by traveling three times up to the ninth floor for passengers, but Mortillalo was eventually forced to give up when the rails of his elevator buckled under the heat. Some victims pried the elevator doors open and jumped into the empty shaft, trying to slide down the cables or to land on top of the car. The weight and impacts of these bodies warped the elevator car and made it impossible for Zito to make another attempt.

A large crowd of bystanders gathered on the street, witnessing sixty-

“…Word had spread through the East Side, by some magic of terror, that the plant of the Triangle Waist Company was on fire and that several hundred workers were trapped. Horrified and helpless, the crowds — I among them — looked up at the burning building, saw girl after girl appear at the reddened windows, pause for a terrified moment, and then leap to the pavement below, to land as mangled, bloody pulp. This went on for what seemed a ghastly eternity. Occasionally a girl who had hesitated too long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged like a living torch to the street. Life nets held by the firemen were torn by the impact of the falling bodies.”

The remainder waited until smoke and fire overcame them. The fire department arrived quickly but was unable to stop the flames, as there were no ladders available that could reach beyond the sixth floor.

Which also meant there was no way to reach anyone on those floors with a ladder to rescue them.

(Picture from the NY Times shows x’s on the windows above where the ladder reaches, indicating where victims jumped.)

[And the water pressure didn’t provide adequate for the water from fire hoses to reach the higher floors.]

The fallen bodies and falling victims also made it difficult for the fire department to approach the building.

(Picture from the NY Times shows forty bodies scattered on the sidewalk next to the building.)

Although early references of the death toll ranged from 141 to 148, almost all modern references agree that 146 people died as a result of the fire: 129 women and 17 men. Most victims died of burns, asphyxiation, blunt impact injuries, or a combination of the three.

The first person to jump was a man, and another man was seen kissing a young woman at the window before they both jumped to their deaths.

So there you have it. Almost a “script” for the Bangladesh fire. Young women doing exhausting labor at pitifully low wages, in a garment factory sweat shop, a fire started and fed by totally unsafe working conditions, a building ill-

So did anyone end up shouldering responsibility for THIS fire?

The company’s owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, who survived the fire by fleeing to the building’s roof when the fire began, were indicted on charges of first-

And quickly ended with an acquittal for both. The defense lawyer convinced the jury that the prosecution needed to prove that the owners specifically KNEW that the exit doors were locked at the time of the fire. In spite of the fact that almost everyone knew that this was “standard procedure” for this sweat shop.

There was a subsequent civil trial, and the owners lost that one. The plaintiffs won $75 compensation to the survivors of each victim. Which ended up being no sweat for Blanck and Harris—their insurance company ended up paying them about $60,000 over their reported losses. About $400 per casualty. They came out ahead.

But surely they at least “learned their lesson” and dedicated the rest of their lives to factory safety…

Harris and Blanck were to continue their defiant attitude toward the authorities. Just a few days after the fire, the new premises of their factory had been found not to be fireproof, without fire escapes, and without adequate exits.

In August of 1913, Max Blanck was charged with locking one of the doors of his factory during working hours. Brought to court, he was fined twenty dollars, and the judge apologized to him for the imposition.

In December of 1913, the interior of his factory was found to be littered with rubbish piled six feet high, with scraps kept in non-

The Triangle Waist Company was to cease operations in 1918, but the owners maintained throughout that their factory was a “model of cleanliness and sanitary conditions,” and that it was “second to none in the country.” [Source]

There was indeed some public uproar over the horrific event, and it did eventually lead to some changes in New York law regarding wages, hours, safety, and working conditions. But of course that involved … shudder … government intervention into business. Which from what I understand is frowned upon greatly by many in our society today.

Some actually seem to consider the improvement in industrial conditions brought about by some of the muckrakers and reformers of the late 19th and early 20th century to be an infringement on The American Way. Because their primary definition of The American Way seems to be … “I’m free to do ANYTHING I want to get rich, with no lousy government intervention. Because after all, Businessmen are gentlemen, and can be counted on to Do The Right Thing without any external interference by do-

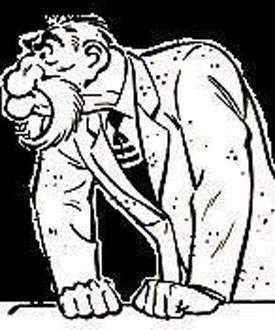

Which puts me in mind of General Bashington T. Bullmoose!

GENERAL BULLMOOSE was created by Al Capp in June 1953 as the epitome of a ruthless capitalist. Bullmoose’s motto “What’s good for General Bullmoose is good for everybody!” was adapted by Capp from a statement made by Charles E. Wilson, the former head of General Motors, when it was America’s largest corporation. He later served as Secretary of Defense under President Dwight Eisenhower. In 1952 Wilson told a Senate subcommittee, “What is good for the country is good for General Motors, and what’s good for General Motors is good for the country.” Li’l Abner became embroiled in many implausible but hilarious adventures with the cold-

Bullmoose had a simple boyhood dream: to possess all the money in the world. He very nearly did. Bullmoose Industries seemed to own or control everything. [Wiki: L’il Abner]

So if Big Business is Good for the Country, any government regulations putting a crimp in the style of any such businesses … are Bad for America. And are thus un-

Oh. Yes. I remember that Eternal Law undergirding The American Way. It’s somewhere in the Bible, I think. At least in principle. It must be. Lots of people who call themselves Christian have been saying so for a long time!

Then again, what any of this has to do with “Love your neighbor as yourself” and “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” and “Don’t forget the poor” and “The laborer is worthy of his hire” is beyond me.