Meet MythAmerica Series

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

The American Way of Business, Part 2

Pinching Pennies ‘til They Screamed

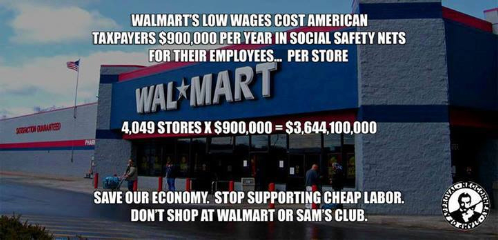

The previous entry in this series started out with an infographic about the devastating effect for smaller nearby businesses that the opening of a Walmart in a city or town often leads to. (In some cases it has almost destroyed whole small communities, when Walmart would move in with a Supercenter, eliminate the competition, become the “only game in town”…and then decide to abandon the community because business wasn’t quite as profitable as it had hoped. Some small towns have never really recovered.)

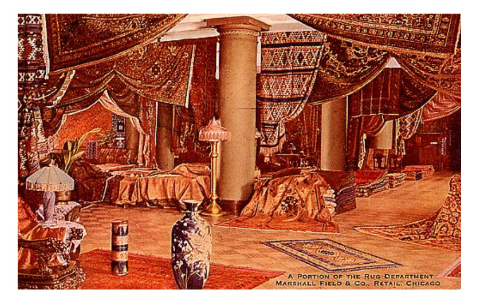

In response we explored the fact that this “Walmart Way” of doing business wasn’t in any way “some new thing” in the U.S. The same devastation was wreaked on small businesses a century ago with the rise of the iconic department stores such as Macy’s, Marshall Field, and Siegel-

Another anti-

I can't vouch for the accuracy of the claims in this infographic. But news stories in recent years have added to this picture. In 2013 Walmart was in the process of building three new stores in the Washington, DC, area, and had announced plans for building three more stores in the near future. But these plans were put on hold as a result of a bill passed by the DC City Council in July that year.. A Washington Post article clarifies what the brouhaha was all about:

Should the bill be signed by Mayor Vincent C. Gray (D) and pass a congressional review period, retailers with corporate sales of $1 billion or more and operating in spaces 75,000 square feet or larger would be required to pay employees no less than $12.50 an hour. The city’s minimum wage is $8.25, a dollar higher than the federal minimum wage.

Once the bill was passed, Walmart came forward and declared that if the bill went into effect, Walmart would not only abandon plans for the three other stores, but perhaps not even finish the stores that are already under construction.

A Huffington Post article gave some background on this stand-

It might not surprise you that Walmart is fighting a ‘living wage’ bill in DC, but, if they win, you might be surprised at how it affects the future of your town. The massive retailer’s recent threat to cancel plans for additional stores in Washington, D.C., is part of a strategy to stifle wages for their own benefit that in turn stifles wages for the entire workforce in an area.

First, some background: theWalmart empire originally spread from Arkansas throughout the rural areas and suburbs of the U.S. These comparably low-

Years before Walmart had a solid plan for a store in DC, the company quietly moved in, joining the DC Chamber of Commerce, making donations to local charities, and hiring lobbyists to help them cozy up to politicians. Construction began on three Walmart stores in the District, with plans for three more in the works. With public construction under way, DC residents began to notice and speak out against Walmart. The DC City Council passed a measure this week that would force Walmart and other giant retailers (any store larger than 75,000 square feet and whose parent company has at least $1 billion a year in revenue) to pay employees a starting hourly wage of $12.50.

In response, Walmart has sought to leverage its political power to strong-

Yes, a similar effort by local government in Chicago in 2006 was undermined by Walmart’s strong-

The HuffPo article declares:

Mayor Vincent Gray should not allow himself to be bullied out of doing what is right for the workers of Washington, DC. After all, retailers can thrive while still paying a living wage. Costco, which pays its employees an average of $45,000 per year, has reported profit increases in recent quarters while Walmart’s sales have suffered. One reason for Walmart’s decline is that many of Walmart’s customers are also employees who, with more and more hours being cut, can’t afford to buy as much as they used to.

Bringing jobs to Washington, D.C. doesn’t need to come at the expense of a living wage, and nor should it. After all, the more you pay your workers, the more money they have to spend buying your products, and the higher your revenues become. Take it from Costco: the living wage works.

It’s not just the “starting wage” at Walmart that causes concern for many folks. Another HuffPo article explains the realities of long-

Last year, HuffPost published internal Walmart documents detailing the company’s wage policies, showing the limited raises many workers see over time. A cart pusher who started out at $8 per hour, for instance, can expect to be earning about $10.60 per hour after six years and a promotion. The company told HuffPost last year that half of its hourly associates in the U.S. make less than $10 per hour.

So is the problem that Walmart, with a $17 billion dollar a year profit, can’t “afford” to pay its employees a living wage, at least enough to keep them from needing public assistance just to feed and house their families? (Although in DC they could afford to pay just one person $10,000 a MONTH to do obscure lobbying for them…lobbying that wasn’t even successful in stopping the minimum wage bill. And let’s don’t get into the likely salary range of executives of the corp. The reality is that they are not a company that has to pinch pennies to keep afloat these days.)

Asked if Walmart objected to the living wage bill because the company couldn’t sustain a $12.50 starting wage, Lundberg said it was more about all retailers being held to the same standards, rather than the largest companies having to play by different rules.

“What it comes down to is a matter of fairness,” he said.

Has the way Walmart has used its financial clout across the country to decimate its competition been “fair”? That is no doubt debatable depending on your personal approach to economics and government, and such topics as taxes, unions, and lobbyists. But is it “UnAmerican” and unprecedented? Nah, Walmart’s methods are as American as Ice Cream, Hot Dogs, and Apple Pie. And have been typical of corporate/capitalist methods since the American Industrial Revolution really got going in the mid-1800s.

Walmart is only imitating the tactics of its forebears of a century ago, the monolithic department stores. So once again, let’s examine what it was like back in those Good Old Days.

Before Huffpo, before Michael Moore’s documentaries, before Mike Wallace’s 60 Minutes exposés, even long before the invention of the radio, reporters were busy doing investigative reporting and exposing the unpleasant underside of many American corporate institutions. One outlet for the work of such reporters a century ago was McClure’s Magazine:

McClure’s or McClure’s Magazine (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism (investigative, watchdog or reform journalism), and helped shape the moral compass of the day.

… McClure’s published such writers as Willa Cather, Arthur Conan Doyle, Herminie T. Kavanagh, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, Lincoln Steffens, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Mark Twain.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, its major competitors included Collier’s, the Saturday Evening Post, and The New Yorker. [Wikipedia: McClure’s]

McClure’s covers often featured pictures of pretty young girls.

Although, since a large proportion of their readers were female, they weren’t averse to the occasional beefcake picture.

The October 1910 issue of the magazine featured an extensive study that had been done on the lives of working girls in New York. It particularly focused on “shopgirls,” young women who were employed in sales or stock work at various New York department stores.

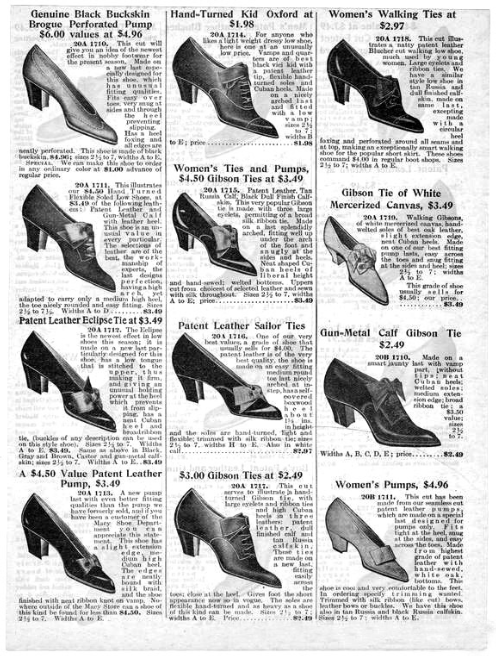

You’ve probably seen old-

So let’s explore what it would have been like to be one of the shopgirls who waited on the elegant ladies who bought such frothy dresses. From the McClure’s story:

(These articles are based upon information obtained through an investigation conducted by the National Consumers’ League, and covering the earnings of working-

One of the first saleswomen who told the League her experience in her work was Lucy Cleaver, a young American woman of twenty-

She stood for nine hours every day. If, in still moments of trade, when no customers were near, she made use of the seats lawfully provided for employees [state law required employers to provide such seating—but did little or nothing to enforce the law], she was at once ordered by a floor-

To put this in perspective, take a look at the shoe styles of 1910.

You can clearly see that these are typical shoes for the shop girls of the time, in this photo of a group headed to work in the morning.

THAT kind of pointy-

So painful to the feet becomes the act of standing for these long periods that some of the girls forgo eating in order to give themselves the temporary relief of a foot bath. For this [Xmas season] over time the store gave her $20, presented to her, not as payment, but as a Christmas gift. The management also allowed a week’s vacation with pay in the summer-

And loyal service to an employer under such exhausting conditions was worth nothing…

After five years in this position she had a disagreement with the floor-

OK, so what did Lucy splurge her $4 or so a week on?

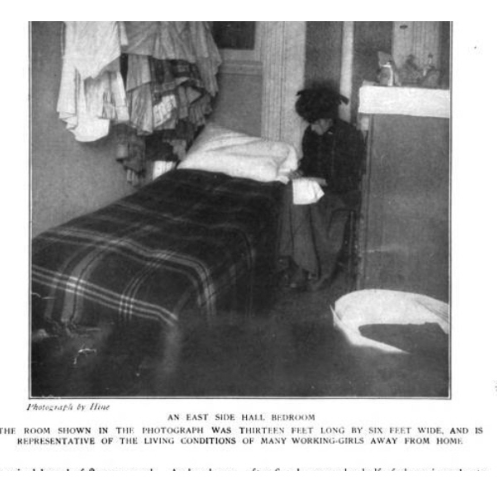

She lived in a large, pleasant home for girls, where she paid only S2.50 a week for board and a room shared with her sister.

Perhaps Lucy and her sister had a room much like this 6 ft. X 13 ft. one shown in the McClure’s article.

Without the philanthropy of the home, she could not have made both ends meet. It was fifteen minutes’ walk from the store, and by taking this walk twice a day she saved carfare and the price of luncheon.

She did her own washing, and as she could not spend any further energy in sewing, she bought cheap ready-

The standard working outfit for almost all shopgirls was a “shirtwaist”—often shortened to “waist” (what we now call a blouse)—usually with long sleeves and high starched collar, and a long skirt.

In order to keep up appearances, and look appropriately prim and proper, she’d have to have a freshly cleaned, starched, and ironed waist every morning, although she could get by with just two skirts.

This [buying cheap ready-

…2 pairs of shoes, $5.00; 24 waists at 98 cents, $23.52; 2 skirts, $4.98; underwear, $2; board, $130; doctor, $2: total, $194.50. This leaves a balance of 86.30. This money had paid for necessaries not itemized — stockings, heavy winter under wear, petticoats, carfare, vacation expenses, every little gift she had made, and all recreation.

She belonged to no benefit societies [cooperative working class groups that would pool “dues” to help pay for health insurance and such], and she had not been able to save money in any way, even with the assistance given by the home. So much for her financial income and outlay. After giving practically all her time and force to her work, she had not received a return sufficient to conserve her health in the future, or even to support her in the present without the help of philanthropy. [In other words, comparable in a way to Walmart workers who must rely on government programs for the poor.] She was ill, anemic, nervous and broken in health.

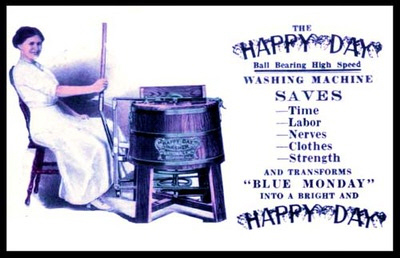

And think about those clothes she had. There were no Laundromats back then, no electric washing machines, and no “permanent press” materials. It is highly unlikely that Lucy had access to the latest improvements in washdays, shown in this 1910 ad for the Happy Day Ball Bearing High Speed washing machine.

(See the lever? You pulled it back and forth continually to make the innards “agitate.”)

No, no Happy Wash Days for her…she likely washed at night, using the poor woman’s washing machine—a tub and washboard. And I doubt if such a tub could hold more than one of those loooong skirts, or even petticoats, she wore.

The processes involved in doing laundry were very harsh, and the kind of waist made out of cheap cloth that was all Lucy could afford would be worn out very soon by the rough handling necessary for cleaning. Thus Lucy’s purchases of two cheap waists per month. White cloth in particular would need lots of effort to keep it looking white—usually with the help of a chemical called “bluing.”

White fabrics acquire a slight color cast after use (usually grey or yellow). Since blue and yellow are complementary colors in the subtractive color model of color perception, adding a trace of blue color to the slightly off-

Most detergents in modern times have a built-

She did her own laundry, including the processes, not only of rubbing the clothes clean, but of boiling, starching, bluing, and ironing. This, after a day of standing in other employment, is a vital strain more severe than may perhaps be readily realized. Saleswomen and shop-

The amount the girls of the St. George’s Working Club found it absolutely necessary to spend in a year for laundering clothes was almost half as much as the amount spent for lodging and nearly two thirds as much as the amount originally spent for clothing. Where this large expense of laundry cannot be met financially by saleswomen [by taking the clothes to a commercial laundry or independent laundress], it has to be met by sheer personal strength. One department-

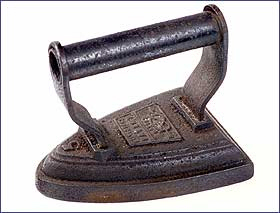

And lest we forget…Lucy would not have been using an efficient electric iron. Back then it would have been irons that you regularly set on a stove to reheat.

Lucy’s story was not anything unusual at all for the time. It was pretty typical. Here’s another young woman with an equally grim story.

Story of Alice Anderson, a Check Girl

… Anderson, a girl of seventeen, who had been working in the department-

She was promoted to the position of sales woman, but her wages still remained $2.62 1/2 a week. She lived with her grandmother of eighty, working occasionally as a seamstress, and to her Alice gave all her earnings for three years. It was then considered better that she should go to live with an aunt, to whom she paid the nominal board of $1.15 a week. As her home was in West Hoboken, she spent two and a half hours every day on the journey in the cars and on the ferry. During the weeks of overtime Alice could not reach home until nearly half past eleven o’clock; and she would be obliged to rise while it was still dark, at six o’clock. after five hours and a half of sleep, in order to be at her counter punctually at eight.

By walking from the store to the ferry she saved thirty cents a week. Still, fares cost her $1.26 a week. This $1.26 a week carfare (which was still not enough to convey her the whole distance from her aunt’s to the store) and the 1.15 a week for board (which still did not really pay the aunt for her niece’s food and lodging) consumed all her earnings except 20 cents a week.

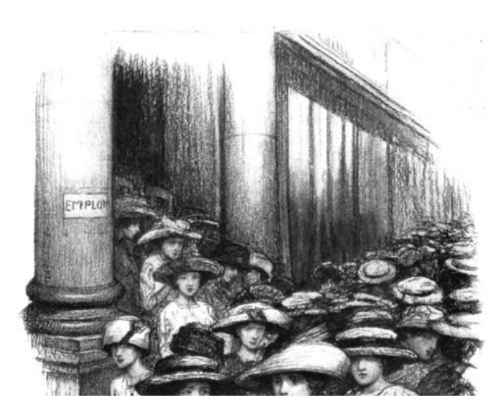

Alice was eager to become more genuinely self-

But instead of things looking up for Lucy, they went downhill from there.

Living on Coffee and Rolls at Twenty Cents a Day

Here she paid six cents a night in a dormitory of a charitably supported home for girls. She ate no breakfast. Her luncheon consisted of coffee and rolls for ten cents. Her dinner at night was a repetition of coffee and rolls for ten cents. As she had no convenient place for doing her own laundry, she paid 21 cents a week to have it done.

Her regular weekly expenditure was as follows: lodging, 42 cents; board [food], $1.40; washing, 21 cents; clothing and all other expenses, $1.97: total, $4. Of course, living in this manner was quite beyond her strength. She was pale, ill, and making the severest inroads upon her present and future health. Her experience illustrates the narrow prospect of promotion in some of the department-

And how about the “benefits package” back then?

… In many of the large department-

As was often done by the muckrakers of the time, one of the investigative researchers found a job in one of the stores to get an inside look at the life of the shopgirl.

Another kind of meanness in human relations was abundantly witnessed by Miss Johnson, the League’s inquirer, who worked in one of the stores during the week of Christmas good will. The “rush” had begun when Miss Johnson was transferred in this Christmas week from the neckwear to the muffler department on the first floor of one of the cheaper stores. All the girls stood all day long — from eight to twelve and from one to eight at night on the first days; from one at noon to ten and eleven at night, as the season progressed; and, on the last dreadful nights, from noon to the following midnight. The girls had thirty-

The work was incessant. The girls were nervous, hateful, spiteful with one another. The manager, a beautiful and extremely rough girl of nineteen, swore constantly at all of them. The customers were grabbing, insistent, unreasonable from morning to evening, from evening to midnight. Behind the counter, with the advance of the day, the place became an inferno of nervous exhaustion and exasperation. In the two weeks of Miss Johnson’s service one customer once thanked her; and one tipped her five cents for the rapid return of a parcel. Both these acts of consideration took place in the morning. Miss Johnson said that this was fortunate for her, as, at one word of ordinary consideration toward the end of her long day’s work, she thought she must have burst into tears.

All of this would be unbearable for most of us even if we were in the best of health. But with no “sick time” available for most of the workers, what was it like to have to work through an illness?

… One girl came, looking so ill that Miss Johnson was terrified. “Can’t you stop, Kitty? You look so sick. For heaven’s sake, go home and rest.” “I can’t afford to go home.” Cross and snappish as the girls were, they managed to spare Kitty, and to stand in front of her to conceal her idleness from the floor walker, and give her a few minutes’ occasional rest sitting down. She went through the first hours of the morning as best she might, though clearly under pressure of sharp suffering.

But at about ten the floor-

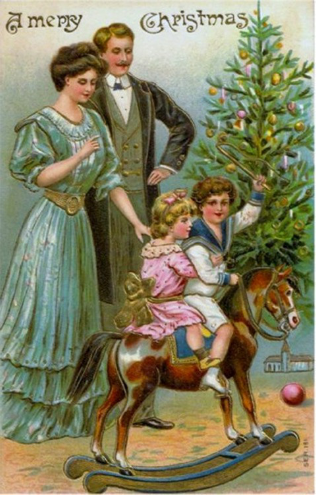

Yes, the time of year that looks so jolly and practically “heavenly” in the old-

…was actually the most hellish time of year for many low class workers. Including especially those who were forced to rub shoulders most closely with the throngs of holiday shoppers.

[New York law regarding minors]… No female employee between sixteen and twenty-

That is to say that, for the holiday season, the time of all others when it might seem wise and natural to protect the health of the younger women working in the great metropolitan markets, for that season, of all others, the State specifically provides that the strength of its youth is to have no legal safeguard and may be subjected to labor without limit.

Indeed, many of these young women were reported to have worked from eight in the morning until ten, eleven, even twelve o’clock at night during the “Christmas Rush”…with a cheap supper furnished by the store as often the only “bonus” they received for this overtime work.

You might be wondering how the big department stores avoided having its high-

“Persons visiting Siegel, Cooper & Co.’s store will be spared the annoyance of seeing over-

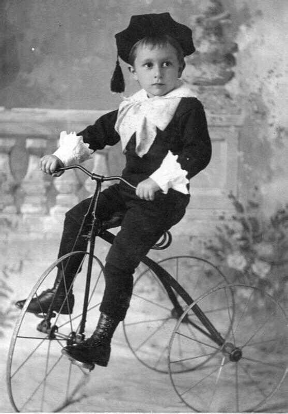

Wouldn’t want little Fauntleroy to get an unpleasant glimpse of a ragamuffin while he and mummy were busy picking out a new velocipede for him in the toy department…

As I originally read these stories of Lucy, Alice, Kitty and others recently, a song popped into my head from my childhood in the 1950s, titled “Silver Bells.” When I’d hear it on the radio back then, it put such a warm glow around the experience of “Christmas Time in the City,” it made me nostalgic for something I’d never even experienced, it seemed so idyllic! (You can see Bing Crosby sing it here.)

Little did I know. I’ll never think of Christmas Time in the City the same way again.

City sidewalks, busy sidewalks

Dressed in holiday style.

In the air there’s a feeling of Christmas.

Children laughing, People passing

Meeting smile after smile

And on every street corner you’ll hear.

Chorus:

Silver belIs, silver beIls

It’s Christmas time in the city.

Ring-

Soon it will be Christmas day.

Not many smiles for Lucy and Alice and Kitty from all the shoppers who would rush home with the treasures they’d bought at the Big Box stores of the day. And I doubt many of these young women had the slightest “Merry Christmas Day.” It was no doubt just a day of total exhaustion, resting up…to go right back to the grind the next day.

No, the heartless American Way of Business didn’t start with Walmart.

~~~~~

Next in this series: Plausible Deniability

Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook