Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8 Pt 9 Pt 10 Pt 11 Pt 12

The Not-So-Gay Nineties

Title

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8 Pt 9 Pt 10 Pt 11

The Not-So-Gay Nineties, Part 10

Lifestyles of the Potlatched and Famous

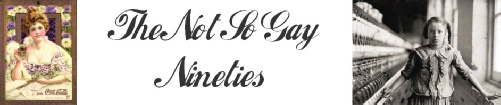

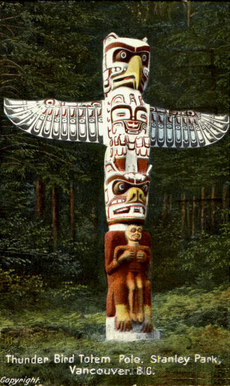

Kwakiutl customs and artwork (particularly ceremonial masks, such as the killer whale and other masks shown below, and totem poles like the one above) are often prominently featured in major Natural History Museums around the world.

Besides their impressive totem poles and wildly fanciful masks, the Kwakiutls are particularly featured in social studies books in grade schools, and anthropology texts in colleges, in connection with their most famous cultural custom, the potlatch. (Other tribes up the coast of Canada, including the Tlingit, also held potlatches, but I am focusing on the Kwakiutl potlatch as it is the most widely-

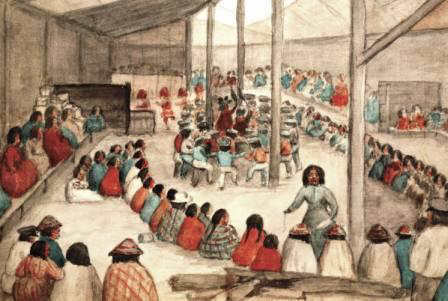

Potlatches were social occasions given by a host to establish or uphold his status position in society. Often they were held to mark a significant event in his family, such as the birth of a child, a daughter’s first menses, or a son’s marriage. Potlatches are to be distinguished from feasts in that guests are invited to a potlatch to share food and receive gifts or payment. Potlatches held by commoners were mainly local, while elites often invited guests from many tribes. Potlatches were also the venue in which ownership to economic and ceremonial privileges was asserted, displayed, and formally transferred to heirs. [Source]

In other words, a potlatch was a big communal party. But as mentioned above, instead of the guests bringing gifts for one or two honored people, as in a birthday or anniversary party, the host of this party provided gifts to all the guests, along with multiple lavish meals. Which, depending on the size of the crowd that came, was all a very expensive proposition. Those organizing a potlatch would plan…and save…all year for this expense.

For big regional potlatches, large “welcoming” totems were set up next to the beaches where visitors would arrive by canoe.

The potlatch might last several days, with lavish feasting throughout. The same creativity these people put into their totems and mask-

As with almost every Kwakiutl get-

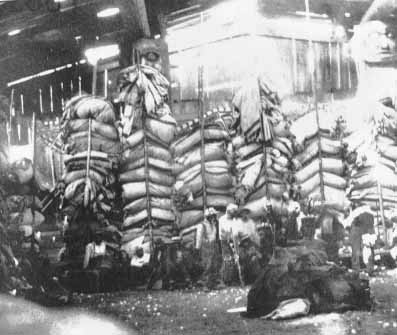

The potlatch was not viewed as just an entertainment event, but as a central feature of the spiritual, economic, and social structure of the society. Individuals established and emphasized their position in the area social hierarchy by the expense and grandiosity of the potlatch they hosted. Although everyone feasted equally at the banquets of food, guests received gifts in proportion to their own position in the society, from lavish gifts of carvings or ornamental baskets or engraved copper shields to those who were, to coin a phrase, “high up on the totem pole,” to simple gifts like blankets (shown first below) or bags of flour (seen in a huge pile near the center of the second picture) to the commoners.

When a person of high status was hosting a potlatch, it was his goal to give away as much as possible—and yet still have wealth left. This established just HOW wealthy and worthy of esteem he was. And the system was consistently “reciprocal.” All those men he had distributed gifts to were obligated to hold their own potlatches, and give HIM lavish gifts too.

It is commonly portrayed as extremely competitive, with hosts bankrupting themselves to outdo their rivals and aggressively destroying property. [ibid.]

This is what I remembered from reading about potlatches in my school years. At times some leaders would just pile up valuable possessions…often ceremonial copper items…and destroy them in a bonfire! This would give them great prestige…and no doubt engender envy in some rivals. Who might try to top them at the next potlatch.

As noted earlier, the Canadian government made it supposedly illegal in 1884 for Kwakiutls (and other tribes which had similar customs) to hold potlatches. This ban wasn’t revoked until 1951. Although the Kwakiutls found ways around the ban and some authorities chose not to enforce it, it did cut into the frequency of such activities, and led to a dwindling of the custom.

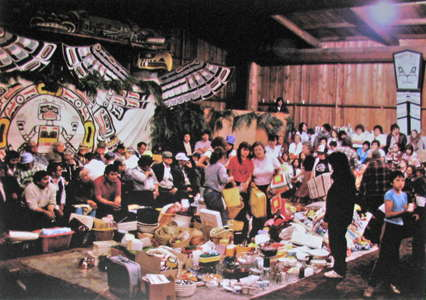

After the lifting of the ban in 1951 it gradually came back, although by 2014 it seems to have lost much of its former “spiritual” and “economic” importance, at least in the minds of the youngest generations. I’m sure some of the “old timers” are very much interested in handing down the deep significance of the customs. But from the looks of photos of modern potlatches being held, I’m suspicious that many of the younger folks view the potlatch as primarily a time of getting together as a community to “honor” their past…and to have fun.

But back when Franz Boas was visiting the Kwakiutl in their villages, and bringing some to the 1893 Columbian Exposition, the ban was fresh:

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884 in an amendment to the Indian Act and the United States in the late 19th century, largely at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it “a worse than useless custom” that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to civilized values.

The potlatch was seen as a key target in assimilation policies and agendas [forcing First Nations people to adopt “white man’s ways” in all aspects of their lives]. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was “by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized.” Thus in 1884, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the Potlatch and making it illegal to practice. Section 3 of the Act read,

“Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the “Potlatch” or the Indian dance known as the “Tamanawas” is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in any gaol or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly, an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment.” [Source]

Franz Boas himself thought the ban was ridiculous and unnecessary—and doomed to failure:

The second reason for the discontent among the Indians is a law that was passed, some time ago, forbidding the celebrations of festivals. The so-

These feasts are so closely connected with the religious ideas of the natives, and regulate their mode of life to such an extent, that the Christian tribes near Victoria have not given them up. Every present received at a potlatch has to be returned at another potlatch, and a man who would not give his feast in due time would be considered as not paying his debts. Therefore the law is not a good one, and can not be enforced without causing general discontent. Besides, the Government is unable to enforce it. The settlements are so numerous, and the Indian agencies so large, that there is nobody to prevent the Indians doing whatsoever they like. [ibid.]

And this brings me to the reason that I have been so “taken” with the story of the potlatch recently, in connection with reading I have done regarding the topic of American culture in the Gay ‘90s. This may seem like a real stretch! But bear with me.

I read these descriptions of the potlatch:

“...a worse than useless custom” that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to civilized values.

“...by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized.”

So let’s examine those statements. It seems to be saying that if a group of people:

… have a custom that includes lavish parties in which people extravagantly spend money for no “productive” purpose, just to maintain a “reputation” among their peers;

…if they just, as the old saying goes, “Burn money” in lavish amounts for “show,” wasting assets and resources for no worthwhile, long-

…such folks are acting “contrary to civilized values,” and cannot be considered Christians, or even civilized.

One would kind of think this should go “double” during times of great financial distress for the vast majority of people in the area where this kind of waste and uncivilized activity is going on. Activity that is not aimed at relieving the suffering of the poor among the people, but rather is limited to just a round of “giving away” to equally prosperous people.

You’d think this would go “triple” when people are starving in the streets…such as during the Panic of ‘93 (and the several years it lasted):

As a result of the Panic, stock prices declined. 500 banks were closed, 15,000 businesses failed, and numerous farms ceased operation. The unemployment rate in Pennsylvania hit 25%, in New York 35%, and in Michigan 43%. [The nationwide “average” was about 20%.] Soup kitchens were opened in order to help feed the destitute. Facing starvation, people chopped wood, broke rocks, and sewed in exchange for food. In some cases, women resorted to prostitution to feed their families.…The huge spike in unemployment, combined with the loss of life savings kept in failed banks, meant that a once-

So in the midst of this it sure would be awful to have heathens blowing fortunes to impress their peers, wasting money to no productive purpose. How uncivilized!

Let’s see…that anti-

Most contemporary sources put the cost of the ball at $250,000 (nearly 6 million dollars in today’s money), including such costs as $65,000 ($1,560,000 today) for champagne and $11,000 ($265,000) for flowers. It was conspicuous consumption at its finest and it worked. [Source]

Of course, this activity…a ball…wasn’t held on the coast of British Columbia. It was in New York City. And it wasn’t planned and hosted by some Indian chief. It was the effort of this 31 year old woman…

Alva Vanderbilt was married at the time to William K Vanderbilt, one of the grandsons of famous railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt. William K’s dad, William H, was the richest man in the world when he died in 1887, and William K (who was already VERY wealthy) inherited a hefty sum, which he’d need to keep up with his young wife’s tastes…

In 1883 she’d just overseen the completion of the building of a new home, which she dubbed “Petit Chateau.”

“Petit” means “little” in French… This chateau doesn’t look all that petite to me, but I suppose maybe she was comparing it to the 130-

That one was the largest private residence ever built in New York, and holds the record to this day (although it was torn down long ago.)

It’s amazing Alva didn’t have another one built after that, to try to top Cousin Cornelius’s…she did NOT like being topped at anything. Or…being on the outside looking in, in any circle.

You see, at the time she married William K, “Society” in New York City consisted of a collection of “old wealth” families who hob-

You’d think that being the wife of a Vanderbilt heir would have ensured Alva a position in that lofty circle. (After all, historians in 2007 estimated the worth of Cornelius Vanderbilt at its height to have been the equivalent of $143 BILLION dollars in modern society. The second or third wealthiest person in US history, after John D Rockefeller, and maybe Andrew Carnegie.)

If that’s what you would think, you would think wrong.

The true “aristocracy” of New York at the time was headed by Caroline Astor, wife of William Backhouse Astor, shown here at age 45 in 1875.

Even before her union with William Astor—the grandson of the American fur magnate John Jacob Astor—Caroline Schermerhorn was prime American aristocracy: She was the daughter of a wealthy merchant and descended from Dutch nobles. In 1890, William and Caroline immigrated to Britain, where they bought their way into British royalty. But their British citizenship, and William’s title of viscount, were only means of advancing their already formidable position in New York society. Caroline’s death [1908] marked the end of old-

Those balls would have been given at the Astor mansion in Manhattan…

Rumor had it that the ballroom in the Astor mansion could only hold 400 people, so the rolls of the “Social Elite” of New York were kept at that number by Caroline. Whether that rumor is correct or not, the term “The 400” often showed up in articles at the time to refer to the New York aristocracy.

The Astors…and Caroline, before her marriage into the Astor family…were descendants of “old wealth” families in America. And by the time Alva came along, the “members” of the social elite of the city had been long established. Any “new” entrants into the inner sanctum were only there by the good graces of Caroline Astor, who could “black ball” anyone who attempted to crash the gates.

Caroline had decided some time before 1883 that indeed they would have to “open the gates” for some new families to come in. But those newbies would have to “prove themselves” to be more than just filthy rich to be admitted. It wasn’t clear exactly what the criteria was, though. There was no published checklist anywhere. It was all in Caroline’s head, and she could add or subtract points based on her own idiosyncratic moods.

The Vanderbilt clan had been very, very rich for a long time. But its fortune had been started by Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt and, as one description has it, “The Commodore was an uncouth man with a habit of chewing tobacco and missing the spittoon, and he had a vocabulary of swear words that had to be heard to be believed.” The Commodore had only died a few years earlier, in 1877, and his bad rep still spoiled the family’s chances to be considered well-

So in spite of the fact that the Commodore had come from an old Dutch family just like Mrs. Astor’s, Caroline Astor would not accept any of his family, even after his death, into the inner circle of the Very Proper 400. They were never invited to her balls, and she had never come formally “calling” at any of their homes to extend social greetings, as was normally expected among the Society set.

“Calling” was a ritual performed among Victorian aristocracy in France and England, and adopted by the wealthy in the US. It involved the use of “visiting cards” (also referred to as “calling cards”)…essentially cards similar to business cards today.

Visiting cards became an indispensable tool of etiquette, with sophisticated rules governing their use. The essential convention was that one person would not expect to see another person in her own home (unless invited or introduced) without first leaving his visiting card for the person at her home. Upon leaving the card, he would not expect to be admitted at first, but might receive a card at his own home in response. This would serve as a signal that a personal visit and meeting at home would not be unwelcome.

On the other hand, if no card were forthcoming, or if a card were sent in an envelope, a personal visit was thereby discouraged. As an adoption from French and English etiquette, visiting cards became common amongst the aristocracy of Europe, and also in the United States. The whole procedure depended upon there being servants to open the door and receive the cards and it was, therefore, confined to the social classes which employed servants.

If a card was left with a turned corner it indicated that the card had been left in person rather than by a servant. [Source]

Receiving a visiting card—presented by their servant, received by your servant, handed on to you—from a social superior was the very first step in getting an invitation to any of their social gatherings. Alva Vanderbilt was not in possession of any visiting cards from Caroline Astor. Which made her persona non grata. Alva found this situation intolerable, as she felt her family’s financial bounty ought to entitle her to all the privileges of wealth…including her family’s acceptance as peers of the other filthy rich families of the city. And invitations to their grandiose parties.

So Alva (at least according to the many stories about the incident that have been passed down through the generations) understanding “the way things worked” in elite society in New York in the 1880s, plotted her entrance into the inner sanctum.

With a “housewarming” for her new Petit Chateau as an excuse, she created plans for the most elaborate, splendiferous, expensive masquerade ball ever given in New York, made sure that all the details were reported in the newspapers, made sure that the “buzz” was good and loud for what a fantastic shebang it was going to be for those lucky enough to be on the guest list.

Word of this party-

Since Miss Carrie was the daughter of THE Queen of New York Society, she would obviously never question that her family would be invited to the Vanderbilt Ball.

And then, the story indicates, came the crushing blow. Carrie found out her friends and their families were invited…but she and her family were not on the list. Carrie no doubt ran weeping to her mother. And her doting mother no doubt discreetly inquired through mutual friends how her invitation could possibly have gone missing.

And Alva discreetly (no doubt) and primly replied that of COURSE it would be improper for her to presume to invite her social betters to a social occasion such as a ball if they had not favored her with a “calling card.”

Caroline was backed into a corner. I’m guessing she figuratively held her nose as she held out a calling card to a servant and requested it be delivered promptly to the home of Alva Vanderbilt. It was delivered, and just as promptly, a servant from the Vanderbilt home showed up at the doorstep of the Astor mansion with an invite to the Big Bash. (From then on, as required by etiquette rules, the Vanderbilts were accepted among the 400.)

And what a Bash it was. As noted earlier, the cost of the whole thing relative to the purchasing value of today would have been about $6 million dollars. For one night’s entertainment, for a few hundred people.

And that brings us back to the potlatch of the Kwakiutls. Because I couldn’t help but think of some of the details of both that seemed eerily “similar.” For instance, a very important part of the Kwakiutl potlatch was solidifying the social hierarchy of the Kwakiutl society. Specific rules came in to play regarding the pecking order of how folks were treated regarding social gatherings. Wealthy chiefs used their wealth in conspicuous ways to elicit esteem from both those lower than they on the totem pole of society and those close to them as peers.

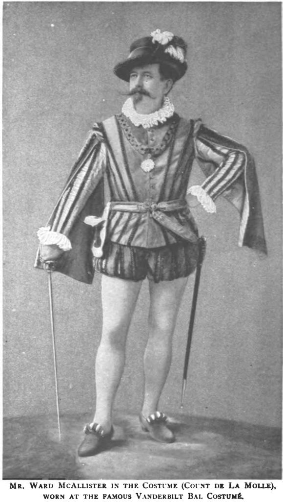

Then there were the costumes. Kwakiutls were big on wearing masks/costumes that made them look like animals. These masks were crafted by master craftsmen, and were no doubt very expensive to produce within that culture. I’m guessing most of the costumes for the Vanderbilt ball were crafted not in New York…but by some of the most expensive “tailors to the rich” in Paris and such.

Miss Ada Smith, a sister of Mrs. Vanderbilt, wore, as a peacock, a dazzling costume of peacock-

Mrs. Sebward Webb, Mr. Vanderbilt’s sister, wore, as a hornet, a brilliant waist of yellow satin, with a brown velvet skirt and brown gauze wings.

This dress was paralleled by another representing a wasp, of purple and black gold gauze, with horizontal stripes of black and yellow, and a transparent gold tissue overdress. A special head-

Then there was the young woman whose nickname was “Puss.” She showed up with an actual taxidermied cat head on her own head, and seven taxidermied cat tails attached to her elegant gown.

And if you thought it was odd that the Kwakiutls would dance with masks of demonic-

Miss Bessie Webb appeared as Mme. Le Diable in a red satin dress with a black velvet demon embroidered on it and the entire dress trimmed with demon fringe-

And then there was the “Hobby-

…the horses were the most wonderful things of the kind ever constructed in this country. The workmen were two months in finishing them. They were of life-

Hostess Alva didn’t go in for the animal look. She showed up as a Venetian Princess.

From the New York Times, March 27, 1883:

Mrs. Vanderbilt’s irreproachable taste was seen to perfection in her costume as a Venetian Princess taken from a picture by Cabanel. The underskirt was of white and yellow brocade, shading from the deepest orange to the lightest canary, only the high lights being white. The figures of flowers and leaves were outlined in gold, white, and iridescent beads: light-

And this is only a miniscule taste of the elaborate finery—and occasional weirdness—worn that night. Think this through…most of the costumes no doubt took weeks or months to create, cost a fortune—and then would have been tossed aside by the wearer, never to be worn again, as casually as one might toss aside a McDonald’s sack after finished with a burger and fries.

Well, not all of them were tossed in the trash at least! Here’s one of the most...flashy…dresses worn that night. This is Alva’s sister-

She literally had an electric battery hidden inside the folds of her dress that powered the “torch” she carried. This was pretty cutting-

Her dress was preserved, and now is displayed at the Museum of the City of New York.

I suppose a few other of the hundreds of costumes may have ended up in museums, but I am more than certain that none of those ladies ever wore their expensive outfits to another social gathering again, nor donated them to the local second-

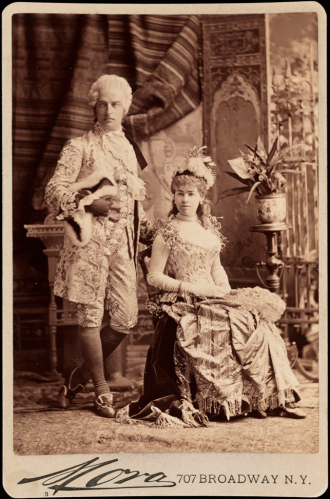

Yes, the gentlemen wore costumes too, but few would have been as elaborate and/or whimsical as those worn by some of the ladies. Some couples came in matching outfits…

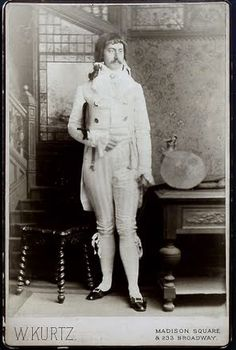

But I’m going to guess that often the woman had some elaborate plan for how she could look the most ravishing, without worrying that her hubby match her in any way. He was free to just look like the gentlemen below.

’

’

The total cost of the costumes worn by everyone has been estimated, in modern dollar value, as over $1,330,000.

I think that figure is in addition to the $6 million or so spent by the hostess on food, drink, décor, flowers, musicians and such.

Which brings me back to the Kwakiutls and their supposedly “uncivilized,” “unchristian” potlatches. Which were “wasteful” and “unproductive.” Because the hosts periodically spent lavishly on food and gifts for guests, with a few, on occasion, “burning up” wealth in a display of the height of their social status.

Uh, yeah.

By the way…all of the attendees at the Vanderbilt Ball would have had their own servants for their mansions, of course. And many of them brought maids and/or valets along with them in their carriages for the evening, to help them with their costumes and such while at the ball. But the scrupulously aristocratic Alva insisted that none of the servants could be brought into the affair. Instead, they all (plus the drivers of the carriages) had to wait out in the carriages all through the many hours of the ball. Ready to depart whenever their employers tired of the novelty of the ball. (The party didn’t totally break up until 3 AM.) Hour after hour in an unheated carriage. In March. In New York.

At least at the potlatches, all members of every social level of the tribe (and often from tribes in the whole area), from commoners to the tribal aristocracy, got to enjoy the celebration that lasted for days, got to feast abundantly, got to watch or participate in the dances and ceremonies, and got gifts to take home. But that was wasteful and unproductive. And unchristian. (Actually, there were specifically tribes that had "converted to Christianity" among the Kwakiutl...they held potlatches too.)

But potlatch activity was, evidently, outside of the sort of “civilized values” shown by the folks leaving their servants out in cold carriages for hours while they danced in horse skins and demon-

Yep, the potlatch celebrations were so comparatively morally bankrupt that they needed to be legally outlawed for over 60 years.

What’s wrong with this picture?

But of course, the Vanderbilt Ball occurred in 1883. That wasn’t really quite the Gay ‘90s yet. Just the prelude.

We’ll explore the Gayness of the ‘90s and its specific ramifications vis-

Money Matters: Please note—This material occasionally refers to how much a certain amount of money from the Gilded Age and early 20th century would be “worth” today. These figures are loose estimates, not intended to be precise—historical “money conversion” from inflation and so on is not an exact science. In general, the figures given are reflecting the “purchasing power” of money—i.e., if you had $10 to spend in 1897, how much would it take you to buy comparable items in modern times? They may also indicate roughly how prices of housing and other necessities compare to wages. The point of including these figures is just to give you a rough “feel” for the incredible wealth of members of “High Society” in the Gilded Age, and the disparity between the money spent by the “average working American” during that time…and the money spent by the Upper Crust.