Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7 Pt 8 Pt 9 Pt 10 Pt 11

The Not-So-Gay Nineties, Part 7

White City to…Ghost Town

Remember the splendiferous Manufactures and Liberal Arts building from the Columbian Exposition of 1893—“largest building in the world” at the time? Here it is as it would have looked before sunset on July 5, 1894 (except without the gondola in the water—the Fair had ended by this time, and the gondolas no longer ran.)

And here is what it looked like at sunrise on July 6, 1894.

You can still see the huge statue of Columbia, arm upraised, that stood at one end of the grand central fountain of the Court of Honor in the White City, looking tiny and pathetic in the distance in the background on the left. Virtually everything else is gone in this photo. What happened??

The Columbian Exposition closed forever on October 30, 1893. But the buildings remained. Over the coming months the contents were gradually packed up and removed. Some of it was shipped back to the countries around the world, or states across the US, that it came from. Some was purchased by organizations, such as the new Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and crated and moved to its new, more permanent home.

Still, the buildings remained. There was even some talk of getting some sponsors and “remaking” the other buildings in the way that the Field Museum organization was doing to the Fine Arts building, so that they could be permanently used. But on the evening of January 8, 1894, a fire started in the building at one end of the Peristyle (the grand colonnade just behind the Columbian statue), spread along and destroyed the Peristyle, and leaped to the Music Hall at the other end and gutted it. That’s the Music Hall at the left end of the Peristyle in the “before” picture below. Don't forget-

The flames then leaped over the Manufactures Building and damaged portions of the roof over the French and Belgian displays. A number of valuable exhibits that had not yet been removed were damaged. But at that point the fire was stopped.

I would suppose after this event the plans for reconstruction may have been reluctantly abandoned. The cost of somehow making the buildings more “fireproof” would no doubt have been prohibitive. They may well have been “uninsurable” at that point! In fact, the insurance industry considered the Fair a “test case” for developing liability standards for fire safety and the hazards related to the new electrical industry. The “Underwriters Laboratory” (remember the “UL approved” labels on most electrical items like hair dryers these days?) was actually started in 1894 by a young engineer named William Henry Merrill who had been hired to examine the electrical safety of the Palace of Electricity at the Fair.

In any case, by June a salvage company had purchased the remaining buildings and had planned to tear them down and salvage the building materials. They waited too long.

On the evening of July 5, a small fire began in the Terminal Building. (Shown below during the run of the Fair in 1893.)

Initial attempts by people on the scene to put it out failed, and by the time the fire department had been alerted and arrived, the fire had spread. Chicago is often referred to as “The Windy City,” as it is right on the lake front of Lake Michigan and subject to stormy gales. The wind was blowing hard the night of July 5, and frustrated all efforts by the fire department to contain the blaze. It reportedly took only two hours for it to lay waste to the all the architectural masterpieces of the entire White City. Look again at that pic of the rubble of the Manufactures Building.

If you could see a 360 degree panoramic view of the site from that same day, it would all look pretty much like the same wasteland. Resembling the devastation wrought by an A-

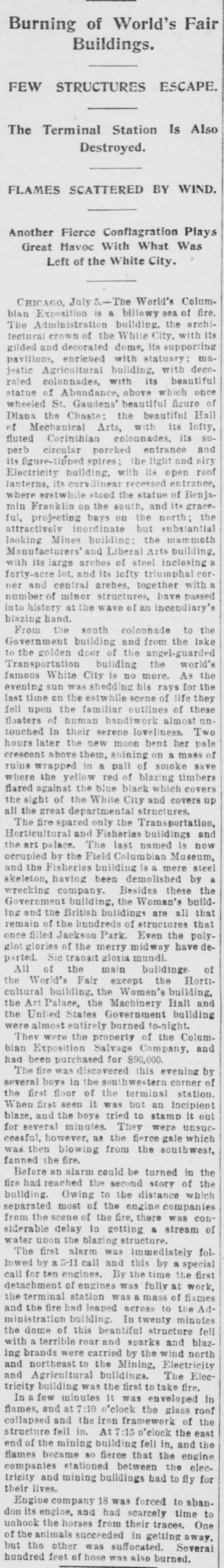

I’m suspicious that even if the water from the fire hoses could have penetrated into the interiors, the result would have been little different. The sheer size and number of those monstrous buildings dwarfed the efforts of the fire crews, as you can see from this excerpt from a news report of the time. The speed with which the fire spread, and how quickly the gigantic buildings were brought down, is just stunning. (See the news clipping pic below for the full text of the report.)

By the time the first detachment of engines was fully at work, the terminal station was a mass of flames and the fire had leaped to the Administration building.

In twenty minutes the dome of this beautiful structure fell with a terrible roar and sparks and blazing brands were carried by the wind north and northeast to the Mining, Electricity, and Agricultural buildings. The Electricity building was the first to take fire.

In a few minutes it was enveloped in flames, and at 7:10 o’clock the glass roof collapsed and the iron framework of the structure fell in. At 7:15 o’clock the east end of the mining building fell in, and the flames became so fierce that the engine companies stationed between the electricity and mining buildings had to fly for their lives.

How terrifying to think of what it would have been like if the fire had started during the regular run of the fair, on a day when tens of thousands were in attendance! There would likely have been many deaths, many more injuries. And the destruction of the contents of the buildings would have run into the many, many millions of dollars.

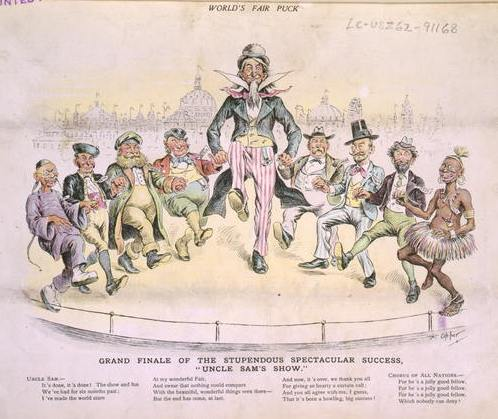

As the author of the news article put it with a fancy Latin phrase, regarding the disappearance of all the wonders of the Fair, both from the fires and from demolition:

Sic Transit Gloria Mundi

“Thus passes the glory of the world.”

Yes, “The Glory of the World.” That’s how the Columbian Exposition was advertised, to draw visitors—and how it was praised by many who did visit. The grandest, most glorious “spectacle” that had ever been planned by man. The envy of the rest of the world.

Here’s how one flowery 19th century author put it, in his “valediction” to the Fair, shortly after it closed in October, in a magazine of the time called The Altruistic Revue.

The gorgeously beautiful White City…no more exists. A rather somber disintegration is fast transforming it from sublime reality to an enchanting dream. With pardonable pride we raise our voice with the overwhelming farewell that comes from the four corners of the planet. The departure of this mystic suburb with the falling of the autumn leaves was as triumphant as its entrance of oriental splendor in the days of buds and blossoms. [It opened in the spring, closed in the fall.] As the Mecca of innumerable hosts from every niche of the globe, a just appreciation of its world-

“Endure imperishably in thought”? Well, I suppose it certainly did for those who were fortunate enough to have been able to afford to travel to Chicago to see it. And I’m going to guess that many of those folks regaled their children and grandchildren with stories about their adventures there, and with how grandiose it all was. So those children and grandchildren may well have kept it imperishable in their own thoughts. Walt Disney’s dad had worked on one of the crews that dismantled the exhibitions at the end of the Fair, eight years before Walt was born. Walt mentioned over the years how fascinated he was with his dad’s stories about it, and that those impressions influenced some of his later plans for Disneyland and Walt Disney world. So indeed some memories of the fair had an indirect “influence” on the future.

But “imperishable in thought” for the average American, in the same way that “everybody remembers” from their history classes in school about Abraham Lincoln, or the signing of the Declaration of Independence, or about the December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor? Evidently not. I am 67 years old now, and I know that for the first 55+ years of my life I’d never heard of the 1893 Columbian Exposition. And if it weren’t for “web surfing” being available to me at one point, I probably still would have never heard of it. I can’t remember what I was googling the day I first came across a website that talked about the Columbian Exposition, but I do know that it was quite by accident.

My grandmother was born ten years after the close of the Fair. And since her kin were dirt poor and lived in the hills of Kentucky—in shacks with dirt floors—I am more than positive that her own parents would not have been able to attend the 1893 Fair. Nor would they have read about it in slick magazines of the time. I’m pretty sure the only periodical reading matter they would have had would have been a Sears Roebuck Catalog. So information about the Columbian Exposition wasn’t something I would have learned about from “family lore.”

It never came up in any history class I took in high school or college. And I had never stumbled across it in any encyclopedia. No, what has made possible the “resurrection” of the Columbian Exposition has been the existence of the Internet …where history buffs can share their obsessions about very narrow tidbits of history. When I first came across Exposition information, only a couple of main websites that featured pictures and stories about it were available. But since that time there has been a flurry of activity among Fair aficionados, and there are now many websites dedicated to the topic, along with several books available from Amazon.com.

And yet—any time I have ever asked friends, or folks on Internet forums or Facebook, if they had ever heard about the Exposition, only a handful have ever responded in the affirmative. In spite of the fact that I have lots of friends who are history buffs themselves. Even the increased info on the Web seems to only have reached a limited audience.

So the Altruisitic Review author was incorrect in his prognostication. The “collective” memory of Americans of the fair has indeed been “perishable.” Even though one other enthusiastic author of the late 1800s insisted that the fair was so monumentally impressive that a century and more into the future, widespread celebrations specifically in memory of the Fair would be held periodically, as if it were an event like the bombing of Pearl Harbor or the signing of the Declaration of Independence!

No, the memory of the Fair was, in essence, as perishable as those buildings that came crashing down…because they weren’t REALLY what they appeared to be. They appeared to be solid architecture for the ages, like the pyramids of Egypt or the grand cathedrals of Europe…or the Great Wall of China. But they were actually little more substantial—and permanent—than a collection of papier-

The same can be said of the Fair itself. For all its claims to be a representation of the magnificence of America at the time, of its ascendance to a role of Major Player on the world scene, of its pride in all its accomplishments, of evidence of its great prosperity—the reality in 1893 was that just outside the gates of the Fair…America was tumbling into the greatest Depression in its history! In fact, in some ways the desperation of this time period was equal to or worse than the “Great Depression” of the 1930s. The grandeur of America implied by the Fair was an illusion.

“Reality” was called the “Panic of 1893.”

As a result of the Panic, stock prices declined. 500 banks were closed, 15,000 businesses failed, and numerous farms ceased operation. The unemployment rate in Pennsylvania hit 25%, in New York 35%, and in Michigan 43%. [The nationwide "average" was about 20%.] Soup kitchens were opened in order to help feed the destitute. Facing starvation, people chopped wood, broke rocks, and sewed in exchange for food. In some cases, women resorted to prostitution to feed their families.

...The huge spike in unemployment, combined with the loss of life savings kept in failed banks, meant that a once-

Yes, it isn't your imagination that an awful lot of "haunted houses" in the movies and cartoons over the years (from those in Scooby Doo to the Psycho mansion) have look like this:

Homes of this international style, called "Second Empire" (referring to the reign of Louis Napoleon of France), were wildly popular among affluent families in the US upper middle class in the years leading up to the time of the Panic of 1893. And indeed, many of them were abandoned by financially ruined families, both during that Panic...and a later one in 1907. The 21st century housing crunch is part of the "nothing new under the sun" reality of the cycles of boom and bust throughout American history.

That fire that broke out on the grounds of the former White City near the Peristyle in January 1894? That was likely caused by “squatters” who moved into the Columbian buildings shortly after the Fair ended and the contents of the buildings were removed. It was one of the coldest, snowiest winters on record in Chicago—which is a frozen city every winter at best. And with the end of the Fair, thousands of men who had been employed in temporary jobs building and maintaining and dismantling the Fair were suddenly “cast off” like an old shoe, into the huge ranks of the already-

Yes, on the other side of the turnstyles into the pseudo-