Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

Pt 1 Pt 2 Pt 3 Pt 4 Pt 5 Pt 6 Pt 7

Walk 1000 Miles in My Moccasins, Part 4

Death of an American Dream

In early 2009, my husband and I moved to the very sleepy, small (9,470 people) town of Cedartown, GA. It’s got a two-

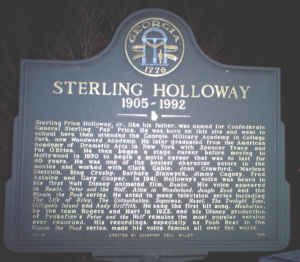

If you’d like to see more of the downtown, check out the 2012 Billy Bob Thornton film, Jayne Mansfield’s Car. In the movie, downtown Cedartown plays … a small town in Alabama in the 1960s! That is pretty much its only claim to fame in over 50 years. An earlier claim to fame was the fact that it was the birthplace, in 1905, and early childhood home of famous character actor Sterling Holloway.

You remember Holloway’s voice, even if you are too young to remember his face—a face that appeared in many, many movies in the 1930s and 40s, starring such actors as Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, and Fred Astaire. From 1941 on he was the voice of a whole army of characters in Disney movies, starting with the Stork in Dumbo and the adult Flower in Bambi. He narrated Peter and the Wolf and Mickey and the Beanstalk, was the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland—and was most famous of all for being, for many years, the voice of Winnie the Pooh.

The town is right proud of its famous son, and there’s a plaque on the site of his birthplace…on the 3-

His family owned a grocery store in town, his dad was the local mayor in 1912, and Sterling got his path to stardom started by putting on his own local neighborhood variety shows in Cedartown as a young boy.

When I lived in Cedartown for less than a year, I assumed that starting Sterling on his path to fame was the town’s own greatest claim to fame. What I didn’t know at that time was that the US Congress was busy that same year giving Cedartown an even more poignant claim to fame for starting another path.

And therein lies a story.

The saga I’ve been telling began with the American Dream story of Cherokee leader Major Ridge, that played out in part about four miles from where I lived in Rome, Georgia.

The beginning of the end of that story began in Cedartown, that is fifteen miles south of Rome.

Previously, we left off with the Cherokee leaders John Ross and Major Ridge in frustration over the failure of their efforts to persuade the Federal Government to support them in their disputes with the state of Georgia. The struggle had been a long one.

Cherokees vs Andrew Jackson: Smithsonian

After years of trading land for peace, the [Cherokee] council in 1822 passed a resolution vowing never to cede a single acre more. “If we had but one square mile left they would not be satisfied unless they could get it,” Ross wrote to Secretary of War John C. Calhoun that October, referring to state Indian commissioners who regularly tried to buy out the tribe. “But we hope that the United States will never forget her obligation to our [Cherokee] nation.”

In 1823, Georgia officials, recognizing Ross’ growing power, dispatched a Creek chief to personally offer him $2,000 (about $42,300 today) to persuade the Cherokees to move. Ross asked for the offer in writing—then took it to Ridge. Together they exposed the bribery attempt in front of the tribal council and sent the emissary packing.

In 1827, Ross assumed more responsibility than ever before …

…[former Principal Chief] Pathkiller died, and Charles Hicks, his assistant and logical successor, followed him two weeks later. The council appointed an interim chief, but Ross and Ridge were making the decisions—when to hold council, how to handle law enforcement, whether to allow roads to be built through tribal land. The two men so relied on each other that locals called the three-

If Ross aspired to be principal chief, he never spoke of it. But Ridge promoted his protégé’s candidacy without naming him, dictating an essay to the Cherokee Phoenix that described removal as the tribe’s most pressing issue and warning against electing leaders who could be manipulated by white men. Until then, every principal chief had been nearly full-

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson forced through Congress the Indian Removal Act.

… Ross spent much of those two years [1828-

“It is too much for us now to be honest, and virtuous, and industrious,” he noted sarcastically, “because then are we capable of aspiring to the rank of Christians and Politicians, which renders our attachment to the soil more strong.”

But Ross refused even to meet with Jackson. Instead, he turned to the U.S. Supreme Court, asking the justices to invalidate Georgia’s removal law.

The Supreme Court had indeed intervened and upheld the Indian’s position. But it didn’t do any good. Jackson defied the Court, and the Congress would not overrule him.

…A month later, Major Ridge’s son John and two other Cherokees were in Washington, trying to determine whether the federal government would enforce the court’s decision. Jackson met with them only to send them home to tell their people “that their only hope of relief was in abandoning their country and removing to the West.”

Jackson’s resolve unnerved the younger Ridge. Gradually, he realized that court victory or not, his people were losing ground. But he could not relay that message to the tribe for fear of being branded a traitor, or killed.

This wasn’t a vain worry. For years before, John Ridge himself had pushed a law through the Cherokee Council setting death as the penalty for selling tribal lands!

[John Ridge] was even hesitant to confide in his father, believing Major Ridge would be ashamed of him.

But the son underestimated his father. Major Ridge judged his people’s prospects by their suffering, and he knew the situation was far worse than anyone had dared to admit. Forbidden to meet by Georgia law, the Cherokees had abandoned New Echota in 1831. Settlers were confiscating their homesteads and livestock. By sharing his thoughts on Jackson, John Ridge helped his father come to the conclusion that the tribe had to at least consider going west.

But Major Ridge kept his feelings private, believing he needed to buy time to persuade his people to think about uprooting. At the same time, he began to wonder how Ross could remain so strident in his resistance. Couldn’t he see that his strategy was bearing no fruit?

Ross met twice with Jackson at the White House, to no avail. When Jackson offered $3 million to move the Cherokees west, arguing that Georgia would not give up its claims to Cherokee land, Ross suggested he use the money to buy off the Georgia settlers.

By spring 1833, the Cherokees were split between a National Party, opposed to removal, and a Treaty Party, in favor of it.

Ross was the head of the National Party, which represented the approach of the vast majority of the Cherokee and their chosen leaders. Major Ridge was head of the minority Treaty Party.

…The majority of the tribe members remained opposed to removal, but the Ridges began advocating the idea more openly—and when they broached it at a council meeting in Red Clay, Tennessee, in August 1834, one Cherokee spoke of shooting them. Father and son slipped away unharmed, but by the end of the summer the Cherokees were trading rumors—false—that Ross and Major Ridge had each hired someone to kill the other.

In September 1834, Ridge visited Ross at his home to put the rumors to rest. They tried to talk as they once had, but the only thing they could agree on was that all talk of murder had to stop. Ridge believed Ross’ intransigence was leading the Cherokees to destruction. Ross thought his oldest friend had become soft, unduly influenced by his son.

The fateful year of 1835 brought Ross back to Washington to try to persuade federal leaders to take the Cherokee’s side in the problems with Georgia. At the same time, the Treaty Party sent John Ridge to try to broker a deal providing for voluntary “removal” of the Cherokee to the Indian Territory.

Ross kept stalling, trying to buy time, hoping against hope that Jackson or the Congress would relent. But the Ridge/Treaty party accepted an offer that would give the Cherokees $5 million in exchange for all the land, and would commit the Cherokees to leaving for Indian Territory. The offer was put to a Cherokee Council vote in October, and was rejected soundly, with only 114 voting for it out of thousands in attendance at the Council gathering.

But Jackson had lost patience, and dispatched US Agent John F. Schermerhorn to get a treaty signed … no matter what. Schermerhorn called for a meeting of the Cherokee Council for December 28 in the abandoned New Echota capital. The National Party refused to attend. So Schermerhorn gathered a small group of men from the Treaty Party, including Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot at Boudinot’s home in New Echota on December 29, had them sign the treaty anyway, and called it a day.

As Major Ridge signed his name, he is reported to have commented, “I have signed my death warrant.”

The treaty provided for a “grace period” of two years from the time of its ratification by the US Congress during which the Cherokee could “remove” themselves voluntarily to Oklahoma. After that they would be removed … involuntarily.

The Ross/National Party was furious.

Those signing the Treaty were not the elected leadership of the Cherokee at all. John Ross gathered signatures of over 13,000 Cherokee on a petition which was sent to Washington in February 1836, entreating the US Government to recognize that the “Treaty of New Echota” was totally invalid.

The petition, written by Ross, said in part:

It [the New Echota Treaty] comes to us, not through our legitimate authorities, the known and usual medium of communication between the Government of the United States and our nation, but through the agency of a complication of powers, civil and military.

By the stipulations of this instrument, we are despoiled of our private possessions, the indefeasible property of individuals. We are stripped of every attribute of freedom and eligibility for legal self-

We are overwhelmed! Our hearts are sickened, our utterance is paralized, when we reflect on the condition in which we are placed, by the audacious practices of unprincipled men, who have managed their stratagems with so much dexterity as to impose on the Government of the United States, in the face of our earnest, solemn, and reiterated protestations.

The instrument in question is not the act of our Nation; we are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people. The makers of it sustain no office nor appointment in our Nation, under the designation of Chiefs, Head men, or any other title, by which they hold, or could acquire, authority to assume the reins of Government, and to make bargain and sale of our rights, our possessions, and our common country. And we are constrained solemnly to declare, that we cannot but contemplate the enforcement of the stipulations of this instrument on us, against our consent, as an act of injustice and oppression, which, we are well persuaded, can never knowingly be countenanced by the Government and people of the United States; nor can we believe it to be the design of these honorable and highminded individuals, who stand at the head of the Govt., to bind a whole Nation, by the acts of a few unauthorized individuals.

Jackson was not impressed with the petition, and ignored it totally. And although many members of Congress, sympathetic toward the Cherokee, protested, the Senate ratified a slightly modified version of the treaty on May 23—by a single vote. Jackson, of course, promptly signed it into law.

For obviously, the reality was that the finer points of treaties were irrelevant. What was relevant was that, as John Wayne famously said in an interview with Playboy magazine in May 1971, the US citizens “needed the land”:

I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them, [the Indians] if that’s what you’re asking. Our so-

Yes, Major Ridge, John Ross, and all the other Cherokee who had bought into the American Dream, had played the game according to the rules, had become “civilized” and “Anglicized,” had worked hard to create a legacy for their own children by establishing plantations and businesses and so on … were just selfish.

Those citizens of Georgia who wanted their plantations … and gold, and whatever other goodies were available on their land… were just trying to “survive.” At least so claimed John Wayne.

Let’s not be naïve here—Andrew Jackson and his supporters were not at all ignorant of the efforts the Cherokee had made. Clear back in 1806 Thomas Jefferson had spelled it out for them.

On January 10, 1806, President Thomas Jefferson addressed a gathering in front of the White House in Washington, D.C. The occasion — a concluding ceremony following a series of meetings with the chiefs of the Cherokee Indian Nation, and others, who had been invited to Washington as a gesture of friendship.

As a part of that ceremony, Jefferson likely distributed “Jefferson Indian Peace Medals” … with his own likeness on them… to the chiefs. Note the date of 1801 on the medal below.

Medals were presented to Indian chiefs on their visits to the national capital and on important occasions such as the signing of a treaty. Federal officials distributed medals when traveling through Indian territories. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark carried a large supply of the Jefferson Indian peace medals on their expedition to the Pacific Ocean from 1804 to 1806. Lewis and Clark called upon the Missouri chiefs to send back “all the flags and medals which you may have received from your old fathers the French and Spaniards. . . . It is not proper since you have become the children of the great chief of the Seventeen great nations of America, that you should wear or keep those emblems of attachment to any other great father but himself…” Missouri chiefs who visited the city of Washington in the winter of 1805-

In his address to the Cherokee chiefs, he made it abundantly clear that the “civilizing” efforts regarding the Cherokee had been very effective.

Jefferson opened with:

“My friends and children, chiefly of the Cherokee Nation,

“Having now finished our business and to mutual satisfaction, I cannot take leave of you without expressing the satisfaction I have received from your visit. I see with my own eyes that the endeavors we have been making to encourage and lead you in the way of improving your situation have not been unsuccessful; it has been like grain sown in good ground, producing abundantly. You are becoming farmers, learning the use of the plough and the hoe, enclosing your grounds and employing that labor in their cultivation which you formerly employed in hunting and in war; and I see handsome specimens of cotton cloth raised, spun and wove by yourselves. You are also raising cattle and hogs for your food, and horses to assist your labors. Go on, my children, in the same way and be assured the further you advance in it the happier and more respectable you will be.”

“You will find your next want to be mills to grind your corn, which by relieving your women from the loss of time in beating it into meal, will enable them to spin and weave more. When a man has enclosed and improved his farm, builds a good house on it and raised plentiful stocks of animals, he will wish when he dies that these things shall go to his wife and children, whom he loves more than he does his other relations, and for whom he will work with pleasure during his life. You will, therefore, find it necessary to establish laws for this. When a man has property, earned by his own labor, he will not like to see another come and take it from him because he happens to be stronger, or else to defend it by spilling blood. You will find it necessary then to appoint good men, as judges, to decide contests between man and man, according to reason and to the rules you shall establish. If you wish to be aided by our counsel and experience in these things we shall always be ready to assist you with our advice.”

Seven treaties with the Cherokee later, the United States, “because he happens to be stronger,” took all Cherokee land East of the Mississippi River. In exchange the Cherokee were given $5 million and an Indian Reservation in Oklahoma Territory. Of course, the Cherokee were never handed $5 million. That’s the amount that was to be spent on their behalf, for public facilities and “mills to grind your corn.” [Source]

Ah, but the reality is not just that the Cherokee were pressured into a “business deal” giving up their homeland and accepting some alternative “property.” The reality is much uglier than that.

The Treaty Party and the Ridge family packed up their belongings in 1837 and moved to the Oklahoma Territory. There they started over. John Ross told the remaining Cherokee not to worry. He thought that he could go to Washington and plan a way for the Cherokee to stay or at least get a better deal for the land. Ross was wrong. [From The Life of Major Ridge]

And that brings us back to Cedartown, Georgia.

For, you see, when the majority of the Cherokee held out hope of a change of heart of the US government, and didn’t follow the Treaty Party to Oklahoma, they set themselves on a path that led in 1838 to… the “Trail of Tears.”

Which started in Cedartown, Georgia. Just .3 mile around the corner and down the street from the birthplace of Sterling Holloway.

When I moved to Cedartown in early 2009, the phrase “Trail of Tears” was only a vague concept in my mind. Perhaps it is in yours too. In 2012 I learned that my homes in Cedartown and Rome had put me physically right in the midst of where it all began. As I began studying the topic, I became mesmerized by the astonishing details of it all. Perhaps you will share my consternation when you read more of the story.