Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica Series

United States of Lyncherdom, Part 1

Incendiary Postcards

The occupying Allied armies entering Germany at the end of WWII in 1945 found horrific conditions in the concentration camps that they liberated. It was mind boggling to US troops, and very soon some of them decided that it would only be fitting to bring the townspeople from nearby cities to view for themselves what they had turned a blind eye to during the war. This occurred in some places, and the reactions of the Germans were captured on film in some photographs that still can be seen on the Internet. Here are three of them.

These types of pictures retain their power even today, long after the events.

The Roth Horowitz Gallery in New York City hosted a photographic exhibit in January and February in the year 2000. One person who attended described the mood at the gallery.

I saw this exhibit. … This small gallery took in only about fifteen people at a time, and the line was long. Watching the viewers as they exited revealed what was inside: people with tears, some with anguish, some looked surprised with the horror they had seen. (Source)

Yes, a picture is often worth 1000 words.

So I’d like to share some of the pictures that were shown at Roth Horowitz that elicited such strong emotional reactions from the viewers.

But what you need to know first is that these were not pictures of WWII Germany. They were pictures of the aftermath of terrorist attacks on American soil.

Perhaps you were under the misconception that such terrorism began on 9/11/2001 with the suicide attacks on the Twin Towers. Or maybe you trace back the beginnings of homeland terrorism to the bombing by Timothy McVeigh of the Alfred P. Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995.

You would be in error in either case. Terrorism on American Soil began long before that, as seen in the photographs shown at Roth Horowitz.

CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK; An Ugly Legacy Lives On, Its Glare Unsoftened by Age

By ROBERTA SMITH

Published: January 13, 2000

New York Times

The photographs that go on view tomorrow at Roth Horowitz, a gallery on the Upper East Side, may never fit comfortably into the history of art, or for that matter, of photography. This is because they are so deeply embedded in the history of hatred, specifically the American history of hatred, which is often a matter of race. They manifest this hatred shockingly, remorselessly, tragically.

The 60 photographs are of American lynchings that took place between 1883 and 1960, mostly but not always in the South. Most of them were taken by professional photographers immediately or a short while after the lynching, sometimes during. All but a few of the victims were African-

Lynching. Now there’s a word you don’t hear much these days. I’m pretty sure I first heard it as a child attending a B-

Yes, I had always, until recently, thought that the term “lynching” was a direct synonym for “hanging.”

How wrong I was. And therein lies a horror tale which has haunted me for the past couple of years, since I first stumbled accidentally over the description of the Horowitz exhibit and began reading about this mind-

Speaking of the Roth Horowitz collection, the writer above goes on:

These images have been collected over the past decade by James Allen, an antiques dealer from Atlanta, along with related material like anti-

The show was initiated by Andrew Roth when he learned that Twin Palms Publishers was planning a book about the Allen-

Although this material has been available to scholars for two years, this is the first time any of it has been exhibited. The show at Roth Horowitz, at 160A East 70th Street, continues through Feb. 12.

These images, most of which are postcard-

Yes, as it turns out, “lynching” is a much more general term than I had understood. And in the context of the history of America, it turns out that the key ingredient rather than rope was often fire.

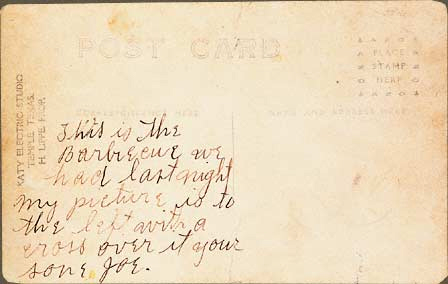

They are postcard-

And here is the horrifying front of that same postcard.

The charred torso is what was left, to be put on display, of a 17 year old young man named Jesse Washington, tortured, hung from a tree, and burned alive, in the front of the court house of Waco, Texas, in 1916 with over 10,000 people looking on—perhaps close to half the population of Waco at the time.

Over 10,000 spectators, including city officials and police, gathered to watch the attack. There was a celebratory atmosphere at the event, and many children attended during their lunch hour. Members of the mob castrated Washington, cut off his fingers [to keep him from climbing the chain by which he was hanging], and hung him over a bonfire. He was repeatedly lowered and raised over the fire for about two hours.

After the fire was extinguished, his charred torso was dragged through the town and parts of his body were sold as souvenirs. A professional photographer took pictures as the event unfolded, providing rare imagery of a lynching in progress. The pictures were printed and sold as postcards in Waco. (Wiki: Jesse Washington)

[DO NOT LOOK TOO CLOSELY AT THIS PHOTO UNLESS YOU ARE BRACED FOR IT. It is said that the victim was still alive when it was taken.]

Describing many of the photos at Roth Horowitz, the author noted:

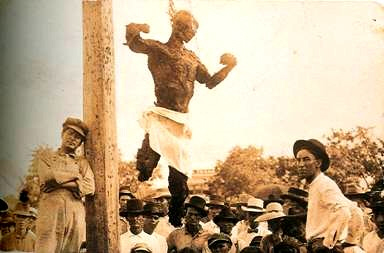

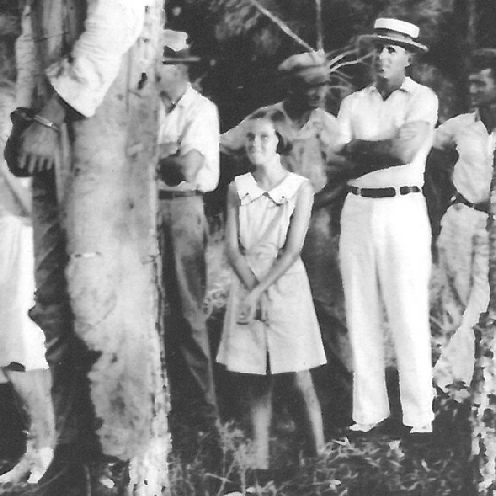

But as Mr. Allen observes in his eloquent afterword, it is not so much the victims that stun, although of course they do. What takes the breath away is the sight of all the white people, maskless, milling about, looking straight at the camera as if they had nothing to be ashamed of, often smiling. Sometimes they line up in an orderly fashion, as if they were at a class reunion or church picnic. Sometimes they cluster around the victim, hoisting children on their shoulders so that they can see too.

No, these are not descriptions of secretive rituals of the Ku Klux Klan, done in the dead of night by people in strange robes with their faces hidden by pointed hoods. They are events that occurred in broad day light—or brightly-

Many of these events did indeed occur in the Deep south … such as this one near Newnan, Georgia

A crowd of nearly 2,000 people gathered in Georgia in 1899 to witness the lynching of Sam Holt [aka Sam Hose], an African American farm laborer charged with killing his white employer. A newspaper described the scene:

Sam Holt…was burned at the stake in a public road…. Before the torch was applied to the pyre, the Negro was deprived of his ears, fingers, and other portions of his body…. Before the body was cool, it was cut to pieces, the bones were crushed into small bits, and even the tree upon which the wretch met his fate were torn up and disposed of as souvenirs. The Negro’s heart was cut in small pieces, as was also his liver.

Those unable to obtain the ghastly relics directly, paid more fortunate possessors extravagant sums for them. Small pieces of bone went for 25 cents and a bit of liver, crisply cooked, for 10 cents. (Source)

From another lurid newspaper account at the time:

The clothes were torn from the negro in an instant. A heavy chain was produced and wound around his body. He said not a word to this proceeding, but at the sight of three or four knives slashing in the hands of several members of the crowd about him, which seemed to forecast the terrible ordeal he was about to be put to, he sent up a yell which could be heard for a mile. Instantly a hand grasping a knife shot out and one of the negro’s ears dropped into a hand ready to receive it. He pleaded pitifully for mercy and begged his tormentors let him die. His cries went unheeded. [Source]

Those events took place about four hours from where I now live in Georgia. And it is not “ancient history.” It was in the lifetime of my own grandfather.

But no, such lynchings weren’t just a southern phenomenon. They occurred all over the country in the time period between the 1870s and the mid-

Will James was lynched to great merriment in 1909 in Cairo, Illinois

“The Frog” or “The Froggie” was a black man implicated in the murder of a white girl, captured in nearby Belknap and taken to the most prominent square in the city and strung up. The rope broke and the man was riddled with bullets. The body was then dragged by the rope for a mile to the scene of the crime and burned in the presence of at least 10,000 rejoicing persons. Many women were in the crowd, and some helped to hang the negro and to drag the body.

Part of the mob then sought other negroes. Another part, at 11:15 o’clock, after battering down a steel cell in the county jail, took out Henry Salzner, a white man charged with the murder of his wife last August, and lynched him. [Source]

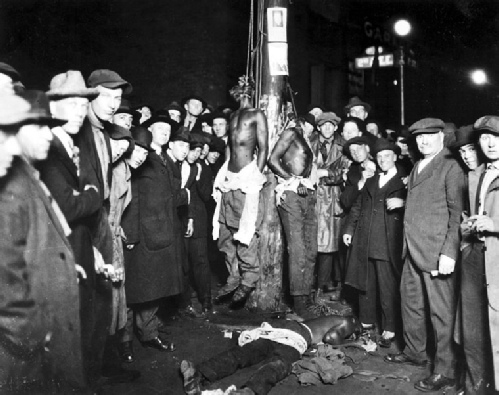

Then there was the lynching of three young black men in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1920.

…three black circus workers were attacked and lynched by a mob in Duluth, Minnesota. Rumors had circulated among the mob that six African Americans had raped a teenage girl. A physician’s examination subsequently found no evidence of rape or assault. …Through the course of the day, a mob estimated between 5,000 and 10,000 people formed outside the Duluth city jail and broke into the jail to beat and hang the accused. The Duluth Police, ordered not to use their guns, offered little or no resistance to the mob. The mob seized Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie and found them guilty of Tusken’s rape in a sham trial. The three men were taken to 1st Street and 2nd Avenue East, where they were lynched by the mob.

Here’s a postcard of the Duluth lynching.

The first verse of Bob Dylan’s 1965 song “Desolation Row” recalls the lynchings in Duluth. Dylan was born in Duluth, and grew up in Hibbing, which is 60 miles northwest of Duluth. His father, Abram Zimmerman, was nine years old in June 1920 and lived two blocks from the site of the lynchings. Zimmerman passed the story on to his son. [Source]

But of course the South was keeping up.

In Paris, Texas, in 1893:

In Paris the officers of the law delivered the prisoner to the mob. The mayor gave the school children a holiday and the railroads ran excursion trains so that the people might see a human being burned to death. [Source]

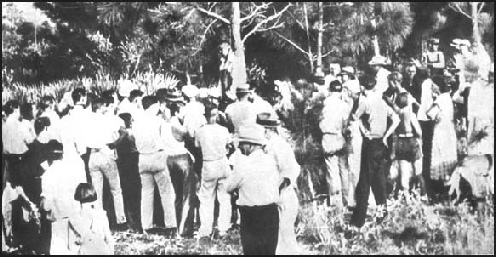

In Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in 1935:

On July 19, 1935, Rubin Stacy, a homeless African-

From the records available, it appears his only “crime” was being hungry and daring to approach the home of a white woman to ask for a handout.

And it was not always males.

One of those women was Mary Turner, a woman in Georgia who wasn’t even accused of a crime.

In May, 1918, 31-

Among those whom the mob killed was another black man, Hayes Turner. Distraught, his eight-

While Turner was still alive, a member of the mob split her abdomen open with a knife. Her unborn child fell on the ground, where it gave a cry before it was stomped on and crushed. Finally, Turner’s body was riddled with bullets. [From the Wikipedia article on Mary Turner. A Contemporary report can be read.]

You know, if it hadn’t been for those horrific “picture postcards” in the Horowitz exhibit, I would find it extremely difficult to believe that those details could possibly be true. Not in the United States of America. Not during the lifetime of my grandparents. Not near Valdosta, Georgia…barely three hours away by modern automobile from my home.

“Witness,” at the Roth Horowitz Gallery, includes 75 photographs of lynchings, taken from the collection of James Allen and John Littlefield. Allen, an antiques dealer from Atlanta, has gathered these historical documents over the past decade. They consist mostly of small-

…Almost all of the lynching victims were African-

Lynchings reached a peak between the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth. A poster in the exhibit, issued in the early 1920s by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and calling for a campaign against these atrocities, gives the figure of 3,436 for the number of lynchings recorded between 1889 and 1922, mostly but not entirely in the former slave states of the South. The actual number is almost certainly higher.

The poster enumerates the official charges against those killed by racist vigilantes: 1,288 victims were accused of murder, 571 of rape, 615 of “crimes against persons” and 333 for “crimes against property.” Alongside these figures are given some of the actual causes of the lynchings: “not turning out of the road to make way for a white boy”; “being the relative of a lynching victim”; “jumping a labor contract”; “talking back to a white man.”

The small photographs and postcards in the exhibit are understandably chilling and gruesome. The great majority show the bodies of the victims hanging lifelessly from trees or telephone poles. In some of the scenes men are depicted staring at the camera before they are killed, as if pleading for their lives. They essentially bear witness for future generations, testifying to the inhuman killings that were about to take place, in a fashion similar to that of photographs of the Nazi Holocaust.

Most striking about the photos is the presence of participants and bystanders. The lynchings were in most cases a kind of community event in which townspeople participated willingly and even enthusiastically. In some cases postcards depicting the killings were sent to friends and relatives. …

As one man who visited the exhibit put it, according to a news account, “Considering the fact that human beings have been executed, for people to smile, to be actually jostling to be in the picture, that’s more stunning than anything else.”

Like these fellows in Duluth.

No, actually I think more stunning was the presence of those children. The little Floridian in the bottom right corner of this pic of the Rubin Stacy lynching would probably be about 85 or so now. Don’t you wonder how what she saw affected her life? Not just the death of that man, but … how the adults around her “modeled” for her how she should feel about it.

The reality was that in many (if not most) of these cases of lynching, the “goal” was not any form of true “justice.” Most of the people in those swarming crowds knew nothing of the “facts of the case” of the person whose grisly death they were witnessing. In far too many of the situations, in addition to the “blood lust” of the crowd in general (obviously this is all VERY close to the displays in the Roman Coliseums in the first century), an unspoken goal was … terrorizing the Negro population (or sometimes Chinese, or Italian, or…) of an area into “keeping their place.”

These were Acts of Terrorism. Committed by American Citizens AGAINST American Citizens. On American soil. Many of them in the lifetimes of people still living.

If you are brave enough to come along, we’ll explore more on this topic.