Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica LITE

You’ll Find that You’re In the Rotogravure

In your Easter bonnet, with all the frills upon it,

You’ll be the grandest lady in the Easter parade.

I’ll be all in clover and when they look you over,

I’ll be the proudest fellow in the Easter parade.

On the avenue, Fifth Avenue, the photographers will snap us,

And you’ll find that you’re in the rotogravure.

Oh, I could write a sonnet about your Easter bonnet,

And of the girl I’m taking to the Easter parade.

Irving Berlin had originally written the “Easter Parade” song for a 1933 Broadway musical revue, As Thousands Cheer. It was later featured being sung by Bing Crosby in his 1942 movie, Holiday Inn.

You don’t hear this old song much any more. In fact, I doubt that most young people have ever heard it. But back before the 1970s, when everyone in your home town listened to the same one local AM radio station, it would have been a regular part of the musical diet of everyone, played endlessly as part of the Easter Song Playlist leading up to Easter. (Along with “Here Comes Peter Cottontail,” probably sung by Gene Autry.)

I can understand why it’s not played much these days. I’m in my 60s, but even I find the old crooning ballads of the 1940s pretty boring in the 21st century. Actually, I didn’t care for them even back in the 1950s (especially once Rock and Roll got going…Buddy Holly beat out Bing Crosby immediately, and the Beatles kept him on the run.) Then again, if any of my readers are nostalgic for that old syrupy sound, here’s the original version of the song, sung by Bing in the 1942 movie Holiday Inn.

As a kid listening to the song on the radio in the 1950s, I remember wondering what a “rotogravure” was, but no one ever told me. It wasn’t mentioned by the DJ on the radio, and I never thought to ask my parents—or look it up in a dictionary.

But of course now, Google and Wikipedia are just a click away. So a few years back I finally thought to look it up. Turns out rotogravure refers to two things. It is first a specific printing process that uses a rotating drum to mass produce a printed document. And instead of being made by a “plate” with raised letters coated with ink and pressed on the paper, it is made by grooves engraved into the surface of the drum, which hold ink and release it onto the paper, including a variety of colors when used, for instance, to print a Sunday comic section of a paper.

And then the term rotogravure also came to refer to the special newspaper sections of photographs which were printed with this process starting around the turn of the last century.

Once a staple of newspaper photo features, the rotogravure process is still used for commercial printing of magazines, postcards, and corrugated (cardboard) product packaging.

…In the 1930s–1960s, newspapers published relatively few photographs and instead many newspapers published separate rotogravure sections in their Sunday editions. These sections were devoted to photographs and identifying captions, not news stories.

Actually, this Wiki author got it wrong on this entry. The newspapers started printing Rotogravure photo sections much earlier than 1930. The process had been perfected by 1879, but was only profitable if used for high-

… Newspapers offered an efficient way to use rotogravure printing because of the industry’s economies of scale. Etching a metal cylinder to produce a page of rotogravure was expensive, and high volume printing was essential in order to reduce the cost per page. Publishers who invested in the new technology, however, were rewarded. Rotogravure printing is so consistent that color variations are rare, ink does not smear, and pages can be handled (and bundled for shipping) immediately. Newly equipped newspapers were able to print large pictorial sections that increased readership and advertising revenue.

On Christmas, 1912, the New York Times published the first complete rotogravure section and similar pictorial sections began to appear in any newspaper able to afford the cost of the press and cylinders. By the end of World War I [1918], forty-

The 1949 Easter Parade movie which featured the song was “set” in 1911. Here is a scene from the movie in which a Rotogravure newspaper photographer is taking a street candid photo of the glamorous character played by Ann Miller.

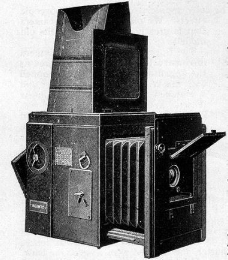

Look closely at the camera that the newsman is using. I’m pretty sure it’s the same model of a 1911 camera shown below.

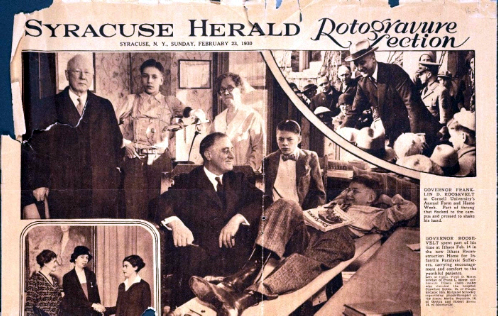

And here’s the real thing, a sample page of a rotogravure section from a Syracuse, NY, paper in 1930. That’s NY Governor Franklin Roosevelt—a paraplegic polio victim himself—visiting young polio victims.

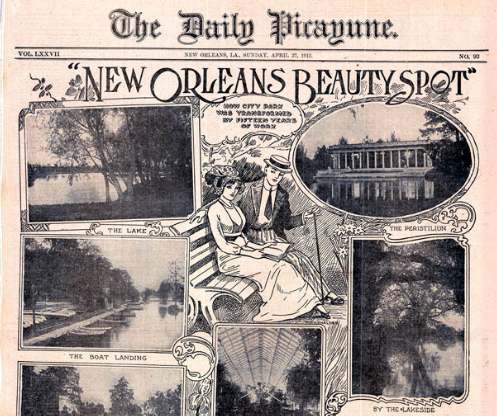

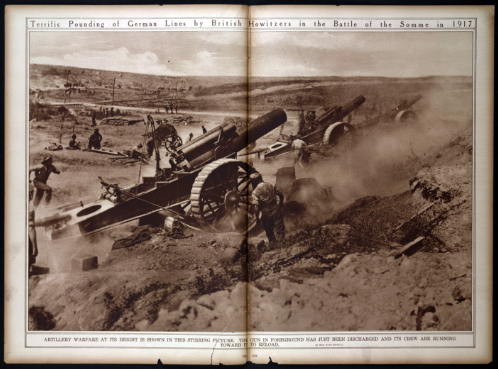

Here are a few more Roto pages from 1913 through the 1930s.

New Orleans, 1913: Pretty scenes about the area.

New York, 1919. The photo is from a the 1917 Battle of the Somme.

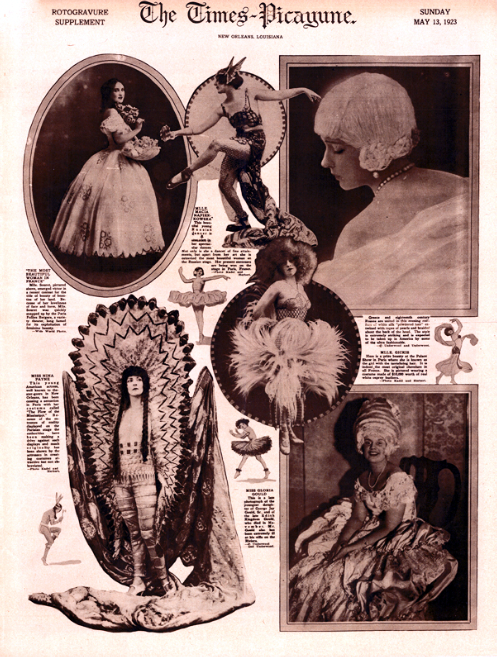

New Orleans, 1923: Contemporary actresses and dancers.

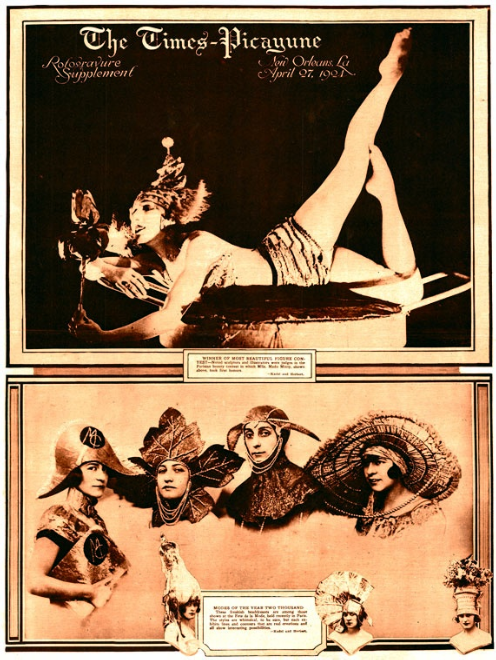

New Orleans, 1924: A beauty contest winner, and a spread showing imagined fashions of the year 2000.

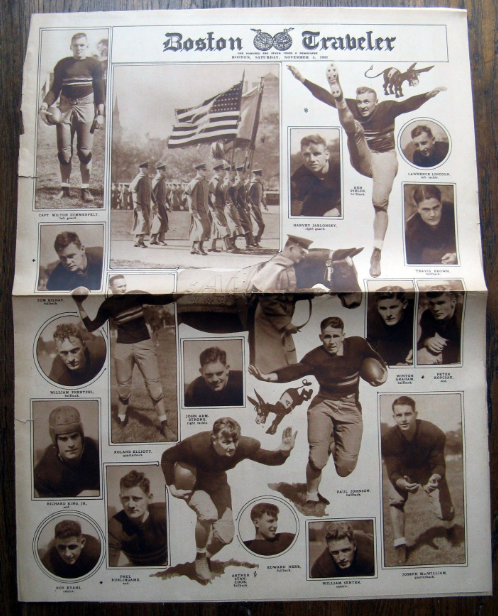

Boston, 1926: Sports spreads were exceptionally popular topics for Rotogravure sections.

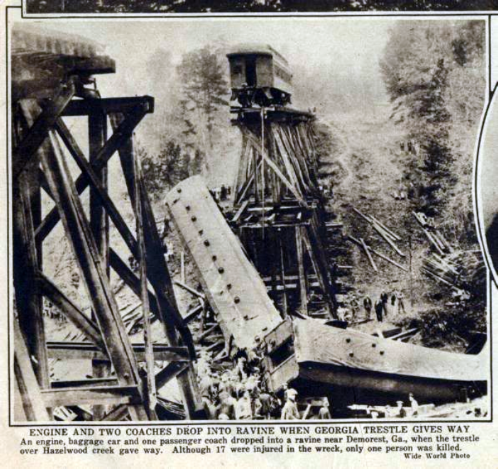

Minneapolis, 1927: A photo about a dramatic train wreck in Georgia.

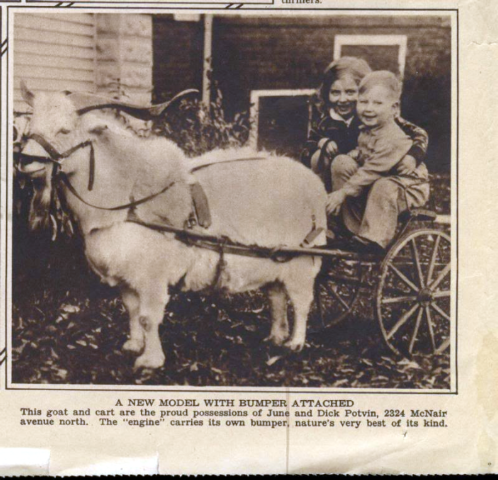

1931, Minneapolis: Just as on Facebook today, pics of cute kids and animals were very popular for Rotogravure sections.

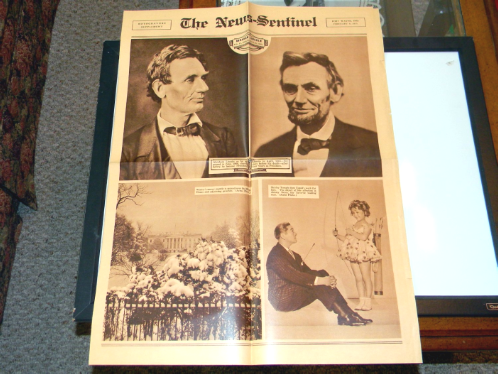

Ft. Wayne, February 9, 1935: Two pics of Lincoln, no doubt related to his February 12 birthday; and a pic of five year old Shirley Temple with her "favorite leading man" of the time, Jimmy Dunn, who had joined her in four movies in 1934.

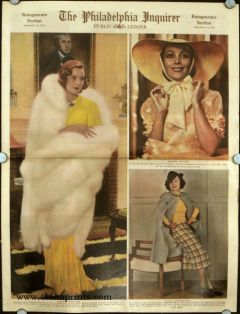

Philadelphia, 1937: Full color Rotogravure section featuring latest fashions.

“Hooray for Hollywood,” another famous song from the 1930s (used in the soundtrack for Academy Award ceremonies right up to today) refers to rotogravures too. It describes young women “…armed with photos from local rotos” who want to become movie stars. In other words, these young women would work at catching the attention of newspaper Rotogravure photographers wherever they could around town, so that they could get their photos in the paper as often as possible, and then clip them out to paste in their professional portfolio to show prospective film employers in Hollywood.

Why did newspapers so quickly adopt the idea of Rotogravure sections even though it meant a large original investment in new equipment?

In 1932 a George Gallup “Survey of Reader Interest in Various Sections of Sunday Newspapers to Determine the Relative Value of Rotogravure as an Advertising Medium” found that these special rotogravures were the most widely read sections of the paper and that advertisements there were three times more likely to be seen by readers than in any other section. [Wiki: Rotogravure]

With umpty-