Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica LITE

Taming the Wild West : The Harvey Girls

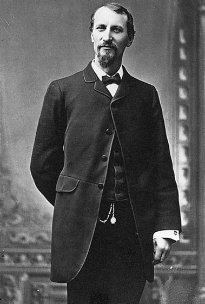

In the early days, the traveler fed on the buffalo. For doing so, the buffalo got his picture on the nickel. Well, Fred Harvey should have his picture on the one side of a dime, and one of his waitresses with her arms full of delicious ham and eggs on the other side, ‘cause they have kept the West supplied with food and wives. (Will Rogers)

Not only did Fred Harvey’s waitresses supply the West with wives, they went a long way toward taming the Wild West of the late 1800s, as explained in this blog entry from the Ventura County Press:

“But don’t call them waitresses. They’re Harvey Girls.”

After the transcontinental railroad made passenger travel feasible in 1869, it fell to [Fred] Harvey to make it fabulous. Before his lunch counters, dining rooms and hotels started popping up every 100 miles, railway riders who weren’t savvy enough to pack their own victuals or who did not possess cast-

Or, as the Wikipedia article on the Fred Harvey Company put it…

Before the inclusion of dining cars in passenger trains became common practice, a rail passenger’s only option for meal service in transit was to patronize one of the roadhouses often located near the railroad’s water stops. Fare typically consisted of nothing more than rancid meat, cold beans, and week-

The “Don’t call them waitresses” article continued…

Not only was the fare offered by middle-

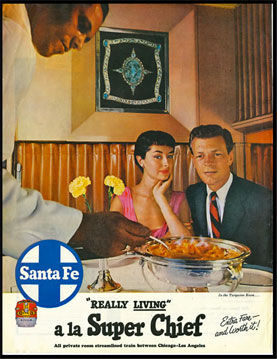

Harvey, a Kansas restaurateur and victimized train traveler, vowed to bring white linen tablecloths, fresh meat and produce courtesy of icebox cars, signature coffee made with pure spring water and four courses of gourmet cuisine served in just under 30 minutes (75 cents) to every Santa Fe stop from Chicago through the Southwest to California and, at its northwestern terminus, San Francisco. At its peak, the Fred Harvey empire included 100 restaurants and 25 hotels.

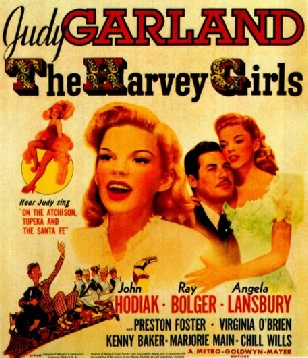

I’m too young to remember The Harvey Girls, the Judy Garland musical based on a historical novel about this slice of history. It came out the year I was born, 1946.

It featured the hit song “On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe.” The song was written specifically for the movie in 1944, but was recorded by several artists, including Bing Crosby, before it appeared on screen, making the hit music charts in 1945. This version by Garland in the movie won the Academy Award for Best Original Song in 1946.

Becoming a classic, it has since been “covered” by many artists, including Petula Clark, John Denver, Harry Connick, Jr.—and an instrumental version even appeared in a couple of Tom and Jerry cartoon shorts. If you are a Tom and Jerry fan, you can see Jerry dance on piano keys to play the song in this Youtube video of “The Cat Concerto“ (interrupting Tom, who is trying to play “The Hungarian Rhapsody.”)

It’s probably just as well I didn’t see the Harvey Girls movie before I knew anything about the topic. As with most historical subjects covered by Hollywood, the plot no doubt took a lot of liberties in presenting “reality” in a sanitized, homogenized, fictionalized way. The movie trailer below advertises it as “MGM’s Gay and Lusty Musical Romance”! (Watch for a young and glamorous Angela Lansbury in a starring part.)

Since I missed the Harvey Girls movie in the theaters, I had never heard about the actual historical Harvey Girls until I stumbled on a short article about them on the Web a while back. Fascinated, I did a little digging to find more info.

Although waitresses are everywhere in the 21st century, waiting tables was considered a man’s job in the 1800s. So all of Harvey’s staffs in his restaurants were male for a while. But all that changed in 1883. (Continued from “Don’t call them waitresses...”)

In 1883, after a midnight brawl involving Harvey’s “likkered up” waiters in Raton, New Mexico, Harvey’s manager suggested hiring females, who would be ‘“less likely to go on tears.’” The ladies proved so popular with customers that Harvey decided to replace all his waiters, advertising in newspapers for ‘“young women 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent, to waitress in Harvey Eating Houses on the Santa Fe in the West. Wages: $17.50 per month with room and board. Liberal tips customary. Experience not necessary.”

Respectable families at first refused to allow their daughters to join this cutting-

And high chances of matrimony.

Not only was a Harvey Girl forbidden to wear makeup or jewelry but, not coincidentally, her uniform (long-

Harvey also took his “in loco parentis” obligation quite literally. Not only did he institute draconian dating policies and hire housemothers to strictly enforce curfews but he kept the girls very busy-

While about half the Harvey Girls returned home after the first contract period, the other half appreciated the security and family atmosphere that Harvey created as well as the generous wages that could be banked, invested in property, business or education or sent back home.

What was probably the biggest draw for Harvey Girls, however, was the prospect of matrimony. American Weekly writer Nina Wilcox Putnam estimated that during the first 22 years (1883-

Some estimates note that eventually over 100,000 women worked for Harvey House restaurants and hotels, and of those, 20,000 ended up marrying one of their customers.

As someone in the Harvey Girls movie put it, “A Harvey Girl is more than a waitress. Wherever a Harvey House appears, civilization is not far behind. You girls are the symbol and the promise of the order that is to come.”

Harvey meals were certainly civilized! Here’s a brief description of the amazing service Harvey was able to ensure in such a rough and tumble time and place and for many decades to come. (From the Wiki article-

The subsequent growth and development of the Fred Harvey Company was closely related to that of the Santa Fe Railway. Under the terms of an oral agreement, Harvey opened his first depot restaurant in Topeka, Kansas in January 1876. Railroad officials and passengers alike were impressed with Fred Harvey’s strict standards for high quality food and first class service. As a result, the Santa Fe entered into subsequent contracts with Harvey wherein he was given a “blank check” to set up a series of “eating houses” along almost the entire route. At more prominent locations, these eating houses evolved into hotels, many of which survive today. By the late 1880s, there was a Fred Harvey dining facility located every 100 miles along the Santa Fe line.

The Santa Fe agreed to convey fresh meat and produce free-

Harvey’s meals were served in sumptuous portions that provided a good value for the traveling public; for instance, pies were cut into fourths, rather than sixths, which was the industry standard at the time. The Harvey Company and the railroad established a series of signals that allowed the dining room staff to make the necessary preparations to feed an entire train in just thirty minutes. Harvey Houses served their meals on fine China and Irish linens. Fred Harvey, a fastidious innkeeper, set high standards for efficiency and cleanliness in his establishments, personally inspecting them as often as possible. It was said that nothing escaped his notice, and he was even known to completely overturn a poorly-

This mutually-

…Harvey initially balked at the suggestion that in-

Given the sparse menu available on planes these days, even on cross-

And to think it all started with a group of girls dressed like nuns!

P.S.

Want to see the whole Judy Garland movie? It’s available through Amazon to rent for $2.99. Harvey Girls.

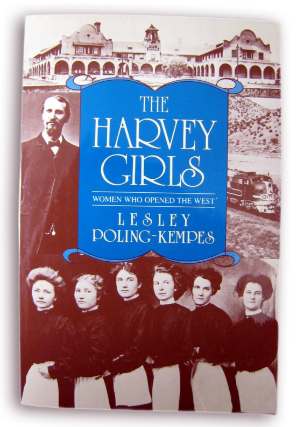

Enjoy reading about “the Old West”? I haven’t read this book show below, but the description on Amazon looks fascinating:

From the 1880s to the 1950s, the Harvey Girls went west to work in Fred Harvey’s restaurants along the Santa Fe railway. At a time when there were “no ladies west of Dodge City and no women west of Albuquerque,” they came as waitresses, but many stayed and settled, founding the struggling cattle and mining towns that dotted the region. Interviews, historical research, and photographs help re-

~~~~~