Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Ruby’s Shoes

I’m suspicious if you say the phrase “Ruby Shoes,” this footwear is what would leap to most people’s minds.

But that’s not what this blog entry is about. It’s not about Ruby Shoes—It’s about RUBY’S Shoes. And I’m suspicious many readers will not recognize this footwear.

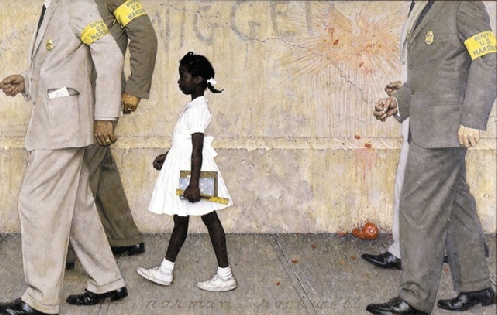

Most older Americans are familiar with the famous 1964 Norman Rockwell painting that he titled “The Problem We All Live With.”

For those who only remember Rockwell from his cheery paintings for covers on the Saturday Evening Post, this painting is quite startling. And no wonder …

In a 1971 interview with writer Richard Reeves, Rockwell explained the unwritten rule laid down by his first editor at the Post: “George Horace Lorimer, who was a very liberal man, told me never to show colored people except as servants.” Lorimer was Rockwell’s editor at the Post for his first twenty years there. The Rockwell cover illustration [see below] from the December 7th, 1946 Saturday Evening Post illustrates the rule in practice. The scene, which is also known as Boy in Dining Car, shows a young boy in a railroad dining car studying the menu with purse in hand, trying to determine the proper payment and tip for the black waiter. [Source]

And it certainly appears that the “unspoken” editorial policy of the Post never changed, even after the death of George Lorimer. During Rockwell’s 45+ year stint painting illustrations for covers of the Saturday Evening Post (323 over the years!), you seldom saw a “colored” face. The main subject of every cover painting was lily white. Rockwell’s Post covers were virtually always “sentimental” and “nostalgic” when portraying the past, and cheery and optimistic when portraying contemporary life. They never addressed “issues” or unpleasantness of any kind—and evidently the Post editorial policy assumed that any portrayal of African Americans as anything more than servants, bystanders, or observers would be … unpleasant for many Post readers.

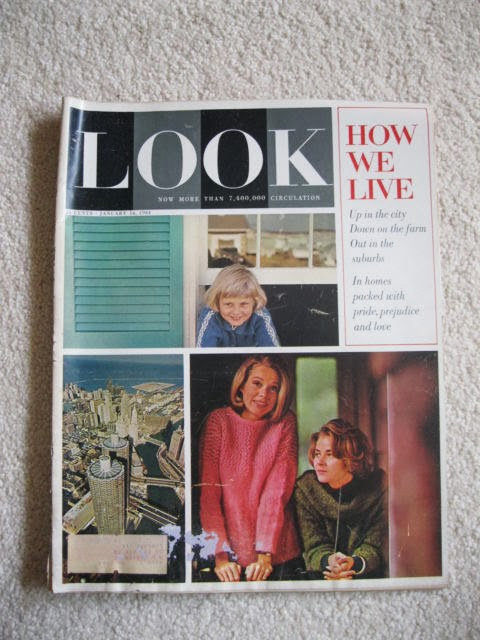

So how did this painting, with a young black girl front and center, addressing visually a very grim, unpleasant American issue, make it into print? No mystery there—it wasn’t painted for the Post. Rockwell had finished his long-

This painting is so iconic that I sure wish I was able to say that I remember seeing it myself in 1964! Actually, I kind of think that I probably did, since my parents subscribed to Look back in those days. But if I did, I’m ashamed to say that it didn’t have the gut-

The institution of slavery had ended in America in 1865 with the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. To this day, many seem to think that ushered in 150 years of “freedom” for the “Negro” population that had been set free at the end of the Civil War. Many seem to think that from that point on, African Americans finally became recipients of the promises of the Declaration of Independence of Equality of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.

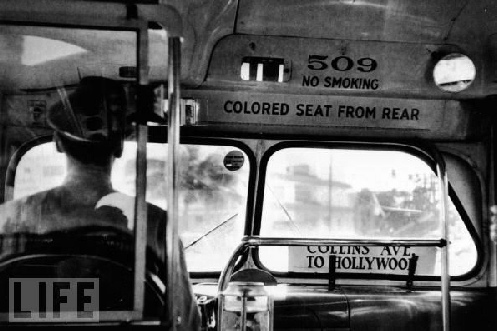

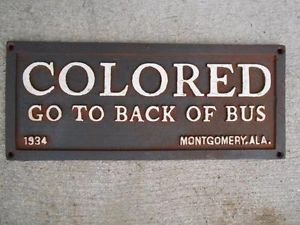

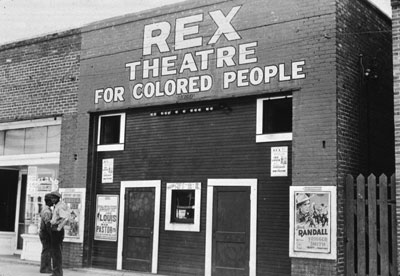

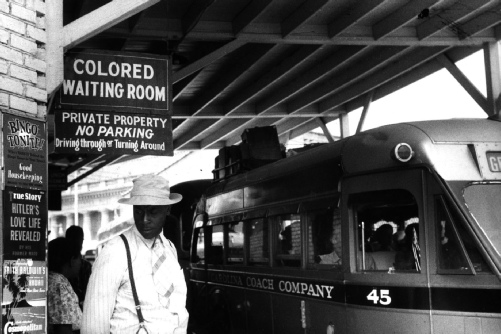

Unfortunately, that is not how the circumstances worked out! After a very short period labeled by historians as “Reconstruction,” during which blacks everywhere including the states of the old Confederacy began voting and becoming an active part of US society, the majority of “Whites” in the Old South decided that they were unwilling to accept that level of equality for those who had formerly had NO equality. Before the turn of the century, “Jim Crow” laws in most of the South had “put the Negro back in his place.” A place with a level of “human dignity” just short of how low it was under slavery.

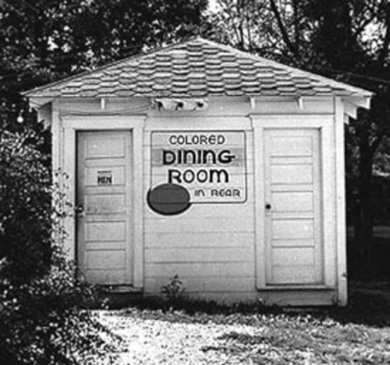

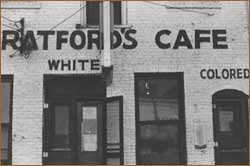

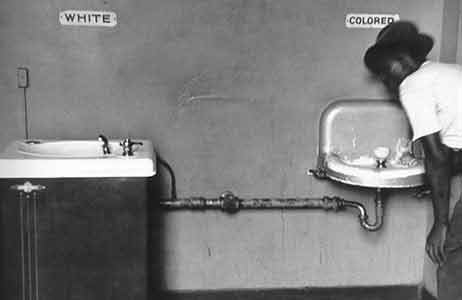

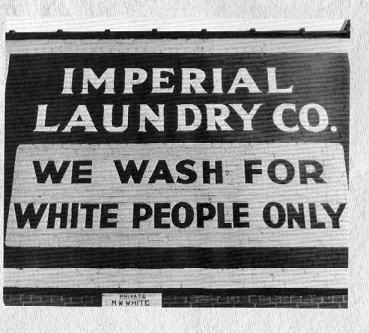

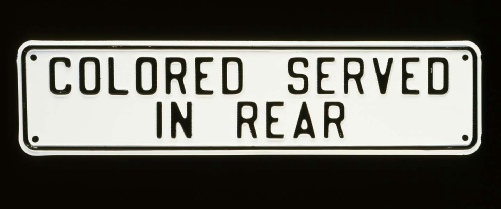

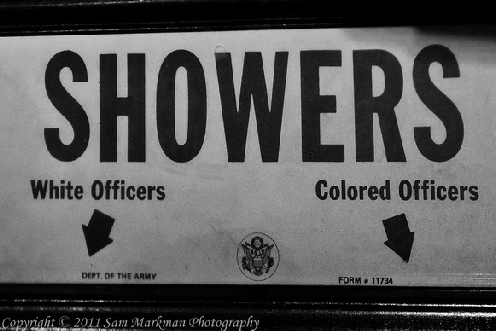

ublic accommodations used by Whites such as trains, trolleys, hotels, restaurants…even drinking fountains…were declared off-

In most areas, voting restrictions of various kinds were put in place that made it close to impossible for the average black person to vote—let alone run for and win public office. Blacks could attend one of the few Negro institutions of higher learning and perhaps get a degree in law or medicine. But they most certainly could not expect to provide legal or medical services to White folks. The mere thought of a black doctor attending to a White woman with an illness was scandalous at best … and a crime at worst—leading perhaps to the doctor being lynched by a vigilante mob.

And this situation continued for almost a century.

“Civil Rights” agitation had periodically been attempted throughout all those years, but even the smallest changes seemed to never come. And then came World War 2. Black men entered the military in large numbers and fought for their country. The needs of War production in US factories with so many men overseas in the active military opened up good-

By the end of the war, many blacks expected that their record of service to their country would “earn” them better treatment and respect. But reality didn’t often line up with those expectations. And especially in the South, Jim Crow laws remained.

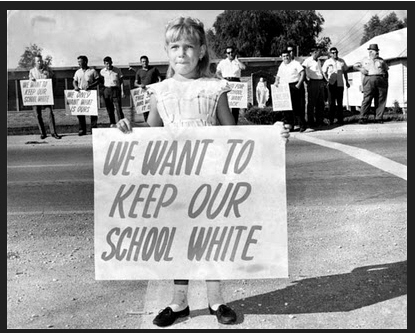

By the early 1950s, many African Americans were no longer able to resign themselves to accept the inequalities of American life for their children and grandchildren. And new life was breathed into the Civil Rights movement. By 1954, the movement had produced its first major success—the Supreme Court ruled that “separate but equal” schools was a totally dishonest concept. Segregated schools were declared unequal by their very nature, and the Court ordered that all public schools in America accept children of any race. Up to this point, even in areas where other Jim Crow laws were not enforced, such as separate drinking fountains, having segregated schools was very common. This was true in many northern and western states as well as the South.

Some areas, particularly in the North and West, grudgingly accepted the orders to integrate. But most areas of the South dug in their heels and resisted:

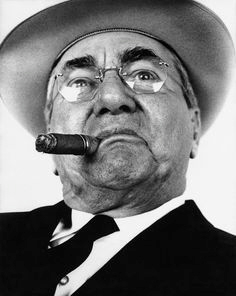

The Southern Manifesto

The Declaration of Constitutional Principles (known informally as the Southern Manifesto) was a document written in February and March 1956, in the United States Congress, in opposition to racial integration of public places. The manifesto was signed by 101 politicians (99 Southern Democrats) from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. The Congressmen drafted the document to counter the landmark Supreme Court 1954 ruling Brown v. Board of Education, which determined that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. School segregation laws were some of the most enduring and best-

Senators led the opposition, with Strom Thurmond writing the initial draft and Richard Russell the final version. The manifesto was signed by 19 Senators and 82 Representatives, including the entire congressional delegations of the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Virginia. All of the signatories were Southern Democrats except two Republicans, Joel Broyhill and Richard Poff of Virginia. However, three Southern Democrats refused to sign: Albert Gore, Sr.; Estes Kefauver; and Lyndon B. Johnson. Their opposition earned them the enmity of their colleagues for a time.

The Southern Manifesto accused the Supreme Court of “clear abuse of judicial power.” It promised to use “all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this decision which is contrary to the Constitution and to prevent the use of force in its implementation.” The Manifesto suggested that the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution should limit the reach of the Supreme Court on such issues.

And here is the primary point of that Manifesto (bolding added for emphasis):

“This unwarranted exercise of power by the Court, contrary to the Constitution, is creating chaos and confusion in the States principally affected. It is destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through 90 years of patient effort by the good people of both races. It has planted hatred and suspicion where there has been heretofore friendship and understanding.”

Yes, they were literally claiming that the Negroes of the South had been perfectly happy with the shabby, ill-

And this is where we introduce Ruby’s Shoes.

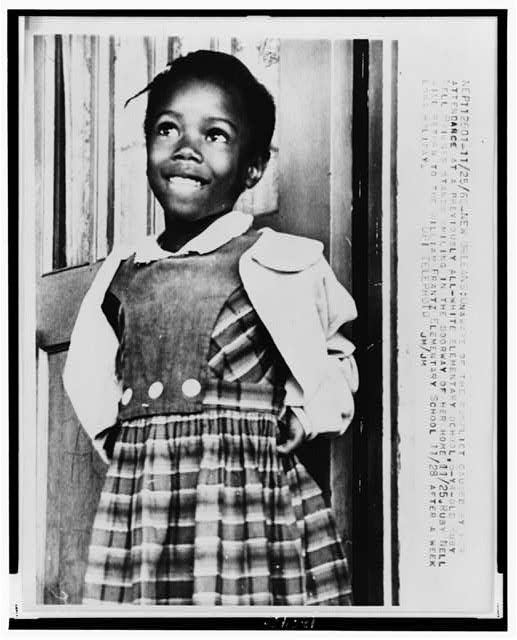

Ruby was little Ruby Bridges of New Orleans, Louisiana.

Ruby had been born the same year that the Brown v Board of Education ruling had been issued, 1954. Thus by 1960 she was six years old. She had attended Kindergarten in an all-

The authors of the Manifesto had been… ahem … misinformed. Many if not most Negroes were NOT satisfied and happy with their treatment under Jim Crow, and some were ready to actively resist the system. This included Ruby Bridge’s mother, Lucille Bridges.

The African Americans weren’t the only ones ready to “resist” something. As in most of the South, the White New Orleans School Board had resisted implementing the 1954 Supreme Court decision.

Two years following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, Federal District Court Judge, J. Skelly Wright, ordered the Orleans Parish School Board to design an effective plan for the desegregation of New Orleans’ public schools. The ruling aroused significant local opposition, however, and parents, school board members, city leaders, and elected officials moved to secure state legislation to overturn Wright’s decision. After four years of circumventing the court-

In early 1960, Ruby was still in Kindergarten. As part of The Plan of the school board, a test was devised to be given to 137 African American students, allegedly to see which ones would be academically suited to attend a White school.

It is said the test was written to be especially difficult so that students would have a hard time passing. The idea was that if all the African-

… In 1960, Ruby Bridges’ parents were informed by officials from the NAACP that she was one of only six African-

Three other six year old girls who passed the test, Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, and Tessie Prevost were assigned to integrate the McDonogh No. 19 Elementary School, another all-

Meanwhile, just as Ruby and the McDonogh Three were getting ready for their first day in their new schools on November 14, the Louisiana legislature was STILL trying to find a way to stop the institution of integration in their state.

In Baton Rouge that morning, legislators opened with prayers for strength and wisdom before proceeding to devise countless schemes to keep black people in their place. They fired the four members of the five-

Sen. Speedy Long of Jena echoed dozens of others in the chamber as he declared “war” on the black race, calling for economic sanctions. “It would mean firing the colored maid, no matter how good she is,” he ranted. “Do not patronize the barber who has a colored shoe shine boy. Do not patronize the service station with a colored grease monkey.” [Nola.com]

And back in New Orleans, things were getting even uglier…

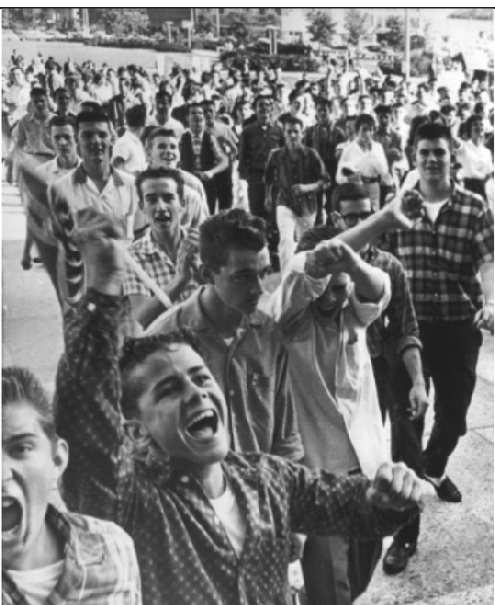

… students from Francis T. Nicholls High School brandished Confederate flags [making sure the public who would see their pics on the news knew that their actions were in defense of their…heritage], a banner marked “KKK” and misspelled signs denouncing “intergration” as they belted out a hymn-

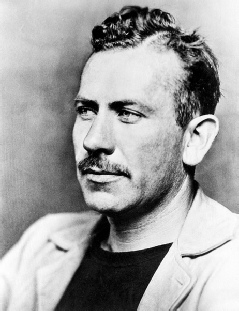

Passing through New Orleans, author John Steinbeck would hear “bestial and filthy and degenerate” threats from the howling white throngs and conclude that he had witnessed a “a kind of frightening witches’ Sabbath.” [Nola.com]

Notice the cheery Christmas greeting on the sign on held by the young man on the right above…”All I want for Christmas is a Clean White School.”

Fearing there might be some civil disturbances, the federal district court judge requested the U.S. government send federal marshals to New Orleans to protect the children. [Biography.com]

And so Ruby’s walk into history began.

On Sunday, November 13, my mother told me I would start at a new school the next day. She hinted there could be something unusual about it, but she didn’t explain. “There might be a lot of people outside the school,” she said. “But you don¹t need to be afraid. I’ll be with you.” [From Through My Eyes by Ruby Bridges Hall]

On November 14, 1960, Ruby and her mother were picked up at their home by US Marshals, who drove them to the nearby school. A crowd was already gathered at the school, anticipating their arrival.

Ruby has described what happened next this way:

“Driving up I could see the crowd, but living in New Orleans, I actually thought it was Mardi Gras. There was a large crowd of people outside of the school. They were throwing things and shouting, and that sort of goes on in New Orleans at Mardi Gras.”

Ruby and her mother got out of the car and were escorted into the school by the Marshals.

But there was to be no spelling or arithmetic lessons for Ruby that day. She and her mother spent the whole day in the school office. Angry White parents would storm into the office and rant for a bit, then rush down the halls to find their children and yank them from the school. ALL of them. Ruby was totally bewildered by at all, and for a time actually didn’t understand that all of this insanity was caused by her mere presence in the school!

At 3:00 PM, Ruby and her mom were escorted out of the school by the Marshals, through the screaming mob, and back to the car, to be returned home.

Later that day she went out to play jump rope with a friend. She taught her friend a catchy little chant she had heard on the street that day, and they jumped rope to it together.

“Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate.”

Yes, innocent little Ruby had no clue what “integrate” meant, and had no idea that this chant had been directed at her.

By the second day, the situation was continuing to deteriorate:

…the 9th Ward also bordered St. Bernard Parish, led by arch-

The day after the schools were desegregated, Perez gave an incendiary speech before a crowd estimated at 5,000 during a meeting of the White Citizens’ Council.

“Don’t wait for your daughter to be raped by these Congolese,” he said. “Don’t wait until the burrheads are forced into your schools. Do something about it now.”

Perez donated a building and operating money for buses and a new private school for the younger children who had left Frantz and McDonogh 19 [the “school” was really an industrial building converted dubbed the “Arabi Elementary Annex”], and he invited older children from the two schools to enroll in St. Bernard public schools, which remained white. [Nola.com]

By the second day, when Ruby returned, there were two other children at the school…although she never got to see them! One was the daughter of a young church pastor named Lloyd Foreman. He had decided he and his family could not go along with the hate-

They were not accompanied by Marshals…they marched past the gauntlet without any protection, receiving the full wrath of the crowd. As did the one other parent who brought her child back to school, Daisy Gabrielle with little Yolanda, shown here almost enveloped by the pressing crowd…not of men in hooded KKK uniforms, but of “mothers” and “grandmothers” determined to keep their children from contamination by tiny little Ruby.

Gabrielle’s mother, Daisy Gabrielle, now 92, was called a communist and countless racial epithets, and she was told that her child could get a disease from being in an integrated school. She had reluctantly removed Yolanda from school early on that first afternoon, fearing for the girl’s safety. But that night, she decided it wasn’t right to give up, so she took Yolanda back the next morning. “It was the principle of the thing,” she said. [Nola.com]

Famous author John Updike wrote in the New Yorker about the situation on 12/10/1960:

Last week Rev. Lloyd Foreman & Mrs. Daisy Gabrielle were shown in the newspapers in the act of escorting their daughters to a New Orleans elementary school … holding the hands of small white-

Yes, just two others to be in the school. But not with Ruby. Nor even with each other:

Each was taught in a separate classroom, remembered Gabrielle, a first grader like Bridges at the time and now a therapist in Rhode Island. “That’s the irony of this: We were still kept segregated,” she said, recalling that she caught sight of Bridges only once, through a slightly open classroom door.

To this day, Bridges doesn’t know who was there with her. “I thought at some point that there were no other kids,” she said, remembering how she heard other children in the hallway and longed to find them and play with them. [Nola.com]

And Pam Foreman remembered the same thing:

Still, she knew other kids were there and wanted to play with them. She’d seen the Gabrielle family walking to school, and she also knew there was a black girl named Ruby there. One time in the hall, she said, she peeked through pane-

Actually, Ruby and Pam did finally get to meet, captured on a CBS special in 2010. Here they are below, swapping memories. That’s Pam on the right, Ruby in the middle, and CBS reporter Michelle Miller on the left.

Both the Foremans and the Gabrielle family faced a lot more problems because of their choice than just the daily walk past screaming women.

… Protesters holding Bibles often surrounded the Foremans’ parsonage, sometimes even throwing rocks at the family pet, which was black and white and thus “an integrated dog,” she said. “And they’d tell Daddy to go live in the French Quarter with all the crazy people and that they’d find a place for me.”

After one too many bomb threats at the house, the family began staying with other ministers, moving from house to house. “We couldn’t check into a hotel, because no one would take us,” Foreman said.

Protesters even waited outside Lloyd Foreman’s church on Sundays, and at one point people threw lightbulbs filled with creosote at the building.

As for Yolanda’s family, her father, James Gabrielle, eventually lost his job over letting Yolanda attend an integrated school, and the family moved to Rhode Island.

For a vivid description of what it was like to be a “turncoat Southerner” in the eyes of your neighbors, someone who accepted integration, have a look at this from the Comment section at the bottom of the Nola.com article quoted above.

In that year I was writing TV commercials for Bell & Howell Corporation (cameras and other stuff) which sponsored a network program (such as “network” was, 50 years ago) called “Bell & Howell Close-

Author John Steinbeck (Grapes of Wrath) was actually on the scene on the second day, when Yolanda and Pam were being brought back to school to stay.

He was in the midst of his famous “road trip” with his poodle, Charley, that he later chronicled in the book Travels With Charley, and read about events in New Orleans, about the reactions of the White community to the four little girls who were “integrating” two schools there. In Texas at the time, he decided to travel on to New Orleans to see the situation for himself. Here, from his book, is his description of what he saw and heard.

“I had seen photographs in the papers every day and motion pictures on the television screen. What made the newsmen love the story was a group of stout middle-

I have learned that in Steinbeck’s original manuscript … he quoted exactly what those Cheerleaders yelled at Pammy’s Daddy, the pastor. But many of the words were much too graphic to get past his publisher’s editors—too much chance of a legal suit! So his description was toned down quite a bit, keeping only the “N” word and “bastard” and perhaps a few other milder terms. I can’t find the original on the Net, but so you will understand how bad it was, in an article about in on the Net, someone who has read it noted, “Let’s just say they included a lot of words sailors and athletes use, plus a lot of –ings.”

When describing the same scenes, a Time magazine article on 12/12/60 referred to the Cheerleader’s performance as an “ecstasy of hatred.”

Here is Steinbeck’s description of the arrival of Ruby Bridges at school on the second day of her journey. I assume it may have been in part this description that influenced details of the painting by Norman Rockwell.

The show opened on time. Sound of sirens. Motorcycle cops. Then two big black cars filled with big men in blond felt hats pulled up in front of the school. The crowd seemed to hold its breath. Four big marshals got out of each car and from somewhere in the automobiles they extracted the littlest Negro girl you ever saw, dressed in shining starchy white, with new white shoes on feet so little they were almost round. Her face and little legs were very black against the white.

The big marshals stood her on the curb and a jangle of jeering shrieks went up from behind the barricades. The little girl did not look at the howling crowd but from the side the whites of her eyes showed like those of a frightened fawn. The men turned her around like a doll, and then the strange procession moved up the broad walk toward the school, and the child was even more a mite because the men were so big. Then the girl made a curious hop, and I think I know what it was. I think in her whole life she had not gone ten steps without skipping, but now in the middle of her first skip the weight bore her down and her little round feet took measured, reluctant steps between the tall guards. Slowly they climbed the steps and entered the school.

Take three minutes or so and click on this link below to have a look at this CBS special report that includes some clips of news film from that period that will give you a “feel” for what it was like, as well as a brief glimpse at the 2010 meeting between Ruby and Pam.

If you watched the little video above, you will have seen the ONE scene from Ruby’s story I can’t get out of my mind. It’s what bothered her most as a six year old about walking the gauntlet daily. Actually, one woman, every day for a long time, threatened to poison her, so she was only allowed to eat what she brought from home. But that wasn’t the worst. The worst was THIS…

Yes, every day at least one “motherly” or “grandmotherly” lady would bring a tiny CASKET with a small black doll in it and wave it at Ruby. THAT gave her nightmares.

“I would dream that this coffin had wings and it would fly around my bed at night, and so it was a dream that happened a lot and that’s what frightened me.”

When I first heard of this aspect of the protests several years back, I was aghast. But I’d never seen an actual photo of this monstrosity. Then, just as I was working on this article, I found the pictures above of this ghoulish insanity for the first time. Yes, that is a Confederate flag unfurled in the crowd behind the casket in the first photo. All these folks were making sure the world knew that they were…defending their heritage.

When I first examined those casket photos, suddenly the faces on the participants distinctly brought to mind other photos I’d seen. Contemplate the absolutely joyful looks on the faces of these people surrounding the casket again…

Remember, this was in 1960. Now go back with me about 40 years earlier, to 1919, to the era of the grandparents of these people. And look at these folks leering cheerfully into the camera.

The 1960s folks were joyous about showing off the effigy of a dead black baby. So what were the folks in the era of their grandparents joyful about showing off? Here is the “full photo” that the close-

Yes, that is no effigy they are gloating over. That is the actual ashen remains of a human being, a black man lynched by the vigilante mob, with his body still smoldering from being set aflame. In a central plaza in Omaha, Nebraska. (Henry Fonda was a young man at the time, and witnessed this from a nearby building. The vision disturbed him for the rest of his life.) The crowd of over 5,000 (some estimates put it as high as 15,000) people had earlier torched the Omaha courthouse, and attempted to lynch the Mayor of Omaha when he tried to intervene in the situation.

The first time I saw the photo above—and many more like it of public lynchings from all over America—I was aghast also. What kind of demonic rage would it take for a huge crowd of people to torture, kill, and torch another human being? In twentieth century America. Actually, many lynchings from that time period included dismemberment of the living victim, and burning him to death. In the public squares of major American cities, in front of thousands of cheering people. Who brought their children to watch the festivities. And who took “souvenirs” of his body parts afterwards, and posed for pictures like the one above to turn into postcards to send to family and friends. If you can stomach it, you can learn more of the details of this mass insanity in a different series on this website titled “The United States of Lyncherdom.”

Here’s what terrifies me about the implications of all of this: it was forty years from the public orgy of rage of those people in that Omaha picture until the similar rage of the people with that baby in a casket. That rage didn’t go away, it just was “sublimated” by circumstances and laws for a time, until it burst out full bloom again in rage against what Steinbeck referred to as “the littlest Negro girl you ever saw.” And of course, the rage continued for years during the height of the Civil Rights movement, as the masses in many places resisted the idea of having to drink from the same water fountains and eat in the same restaurants and go to school with people whose skin was a different color. It has now been 55 years since 1960. I have no feeling of confidence that the communal rage has just somehow “disappeared.” What would it take for it to come to full bloom again?

Here’s how one blogger put their own response to learning about the baby casket insanity:

I also think about all these white people in the crowd. Not only did they feel obligated to come for a chance to harass the little soul, but they came prepared. Some of them brought these little babies’ caskets with black dolls inside. So they could make their point clear to the six-

Where does one get a baby’s casket? At a funeral home? Supermarket? Did they build the caskets themselves? As a family activity? So they come from a church service or a family gathering on Sunday and tell their kids:

“This is what we’re gonna do tonight. We’ll buy a black doll. Then we’ll go to a workshop and build a small casket. Tomorrow, we’ll put the doll in the casket and wave it in the face of this six-

Who are all these people?

… Are they still around? Some of them should be alive. I wonder if they kept the babies’ caskets.

Yes, I wonder many things about these hellish scenes myself. I don’t doubt some of the people are still alive. What did they do with that demonic rage? And more importantly, even among those long dead, how many of them succeeded in planting the seeds of potential demonic rage in their own children and grandchildren before they passed on? … And what would it take to have it come roaring out again? What would it take for once again the howls of the roaring crowd, just like those in the Roman Coliseum in the first century, to be broadcast on international TV, as they were in 1960 as described by John Steinbeck.

A shrill, grating voice rang out. The yelling was not in chorus. Each took a turn and at the end of each the crowd broke into howls and roars and whistles of applause. This is what they had come to see and hear. No newspaper had printed the words these women shouted. It was indicated that they were indelicate, some even said obscene. On television the sound track was made to blur or had crowd noises cut in to cover. But now I heard the words, bestial and filthy and degenerate. In a long and unprotected life I have seen and heard the vomitings of demoniac humans before. Why then did these screams fill me with a shocked and sickened sorrow?

Thankfully, I also have no doubt that some…hopefully many… children and grandchildren of these screamers were able to get free from that curse and renounce the rage. Here’s one example. This is from the “Comments” section at the bottom of the 2010 Nola.com article excerpted in places in this blog entry.

… I was in a Catholic high school that year, and one of the priests allowed us to watch the ugly spectacle on a borrowed television, to mixed reactions from my classmates. (We already had one dark-

Praise the Lord for those kids who were able to reject the inheritance of hate and rage.

But we are not through with Ruby’s story yet. We just made it to Day Two of the siege.

Meanwhile, all of the teachers had refused to continue teaching at the school, while a Black student was enrolled – except one. When Ruby and her mother got safely inside the building, on the second day, they were warmly greeted by a young, White woman, who said, “Good morning, Ruby. Welcome. I’m your new teacher, Mrs. Henry.” Although Mrs. Henry seemed nice, Ruby was still apprehensive because she had never been taught by a White teacher before. [Source]

Barbara Henry was from Boston, and was the only teacher, at William Frantz, who was willing to teach Ruby. Mrs. Henry escorted them to an empty classroom and told Ruby to choose a seat. Day after day, for the entire school year, they sat next to each other, in that empty classroom and worked on Ruby’s lessons. Mrs. Henry made school fun, and they did everything together. Ruby couldn’t go out in the schoolyard for recess, because the other children were also protesting, so Mrs. Henry organized games in the classroom; and for exercise, they did jumping jacks to music. Mrs. Henry became Ruby’s best friend and helped her forget about the angry world just outside. Neither of them missed a day of school that first year. [Source]

But Ruby’s mother had other children to care for and a job. Starting on the third day, Ruby had to run the gauntlet of protestors all by herself…with, of course, her “body guards” around her to get from the car to her school room.

… Former United States Deputy Marshal, Charles Burks, later recalled, “[Ruby] showed a lot of courage. She never cried. She didn’t whimper. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we were all very, very proud of her.”

Ruby made it through the school year, but her family paid a very high price.Ruby’s father was fired from his job, local White store owners even refused to sell groceries to them, and Ruby’s grandparents in Mississippi were forced off the farm where they had been sharecroppers for 25 years.

Much more could be said about the challenges Ruby faced, and what happened to her in later years. Here’s Ruby and her teacher Mrs. Henry reunited.

And here she is with her younger self.

If you’d like to know more, this article is a good place to start:

Ruby Nell Bridges: Possibly the Bravest Ever Little School Girl

And here is a link to a six minute Youtube video interview—by a young student—with Ruby in 2010.

But there is one aspect of this whole story we haven’t covered yet. Just what got Ruby through the times of fear, especially after her mother could no longer be with her as she went to school and came home every day? Here are some excerpts from a Guideposts story about Ruby that will make this clear. It starts on the third day of Ruby’s journey, in Ruby’s own words:

The next morning my mother told me she couldn’t go to school with me. She had to work and look after my brothers and sister. “The marshals will take good care of you, Ruby Nell,” Mama assured me. “Remember, if you get afraid, say your prayers. You can pray to God anytime, anywhere. He will always hear you.”

That was how I started praying on the way to school. The things people yelled at me didn’t seem to touch me. Prayer was my protection. After walking up the steps past the angry crowd, though, I was glad to see Mrs. Henry. She gave me a hug, and she sat right by my side instead of at the big teacher’s desk in the front of the room. Day after day, it was just Mrs. Henry and me, working on my lessons.

… The people I passed every morning as I walked up the school steps were full of hate. They were white, yet so was my teacher, who couldn’t have been more different from them. She was one of the most loving people I’d ever known. The greatest lesson I learned that year in Mrs. Henry’s class was the lesson Martin Luther King, Jr., tried to teach us all. Never judge people by the color of their skin. God makes each of us unique in ways that go much deeper.

From her window, Mrs. Henry always watched me walk into the school. One morning when I got to our classroom, she said she’d been surprised to see me talk to the mob. “I saw your lips moving,” she said, “but I couldn’t make out what you were saying to those people.”

“I wasn’t talking to them,” I told her. “I was praying for them.” Usually I prayed in the car on the way to school, but that day I’d forgotten until I was in the crowd. Please be with me, I’d asked God, and be with those people too. Forgive them because they don’t know what they’re doing .

“Ruby Nell, you are truly someone special,” Mrs. Henry whispered, giving me an even bigger hug than usual. She had this look on her face like my mother would get when I’d done something to make her proud.

And what about Ruby’s Shoes? After reading about Ruby, I decided that it would be appropriate to ask my Photoshopping granddaughter to give Ruby some Ruby Shoes in this famous picture.

And after I came up with that idea, I discovered I wasn’t the first person to make the connection between Ruby’s journey and Dorothy’s in her Ruby Shoes.

When singer-

To help her son, McKenna came up with a song about Ruby. “I actually wrote that for his extra credit,” McKenna said. “It was his oral presentation of that book report. He got an A, by the way. That song has just been so good to me, because I ended up meeting Ruby Bridges, and she came and met my kids.”

McKenna also got to play the song on Oprah in 2005, which made it a viral hit on iTunes, and brought attention to both McKenna and Bridges. [Mental Floss]

Hear it on the Youtube video lined below, and in case you can’t clearly hear all the words, I’ve included the lyrics below. The photos accompanying the video include some of Ruby from that time period, some from other anti-

Lori McKenna Ruby’s Shoes

Ruby’s shoes would take her

A mile or so to school every day

Where the white people hated her

They’d scream and hold signs and tell her to go away

But Ruby’s will was stronger

Than the bigots with the signs could ever know

She stopped every morning on the corner

And prayed that someday the pain would go

And she’d stop and she’d pray

That all the hatred would go away

She was only six years old but she knew

Walk a mile in Ruby’s shoes

Ruby sat alone in the classroom

She never dreamed the other children wouldn’t come

They hated her for the color of her skin

Well color is such an amazing illusion

She’d stop and she’d pray

That all the hatred would go away

She was only six years old but she knew

Walk a mile in Ruby’s shoes

Now Ruby knew about Dorothy

And the ruby shoes that she wore

She wondered about Oz sometimes

Well, well no other child ever walked her shoes before

And she’d stop and she’d pray

That all the hatred would go away

She was only six years old but she knew

Walk a mile in Ruby’s shoes

Ruby, if birds can always fly

Why oh why can’t you and I?

Ruby’s shoes would take her

A mile or so to school every day

Where the white people hated her

They’d scream and hold signs and tell her to go away

And she’d stop and she’d pray

That all the hatred would go away

She’d stop and she’d pray

That no other children would be raised this way

Ruby’s shoes

If birds can fly

Then why oh why

If birds can fly then why oh why can’t I