Exploring our past to sort out myth from reality

Share this Page on

Facebook or Twitter

These are the voyages of the TimeShip Anachron.

Our Mission: To boldly explore the past, dispelling

mythinformation and mythconceptions

of American History along the way.

Visit us on Facebook

Visit us on Facebook

Meet MythAmerica: SNAPSHOT

Pony Tales:

History of the Pony Express

Back in the late 1990s, my husband and I took a trip “out West” from Michigan to visit our daughter who was living in Douglas, Wyoming, at the time.

At one point we stopped at a restaurant/gift shop somewhere on the High Plains. I’m guessing it may have been near North Platte, Nebraska. Or maybe Kearney, or Gothenburg.

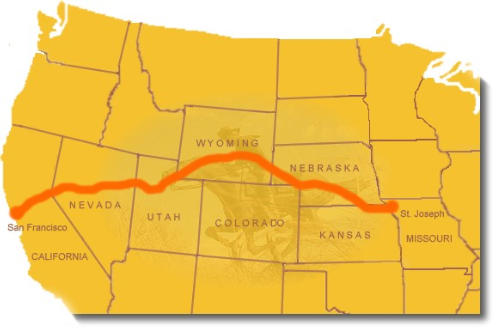

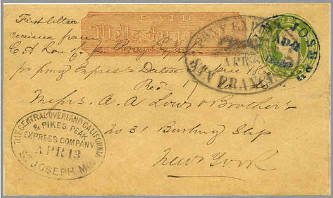

Whichever it was, the route we were on in western Nebraska matched very closely for a short while the route of the old Pony Express, which went from St. Joseph, Missouri (near the intersection of Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska, located right on the Missouri River) across the Plains and Mountains to Sacramento, California. (Most of the mail was actually headed ultimately to San Francisco. It was transferred at Sacramento from ponies/horses to a steamer that took it the final stretch down the Sacramento River to San Francisco. Occasionally, if a steamer was missed, riders would continue on and deliver the mail to Oakland.)

I don’t think the restaurant was on the exact spot of a Pony Express station, but the PEX was obviously a hot topic in the area, and the gift shop played upon the PEX connection as a tourist attraction, with PEX themed souvenirs.

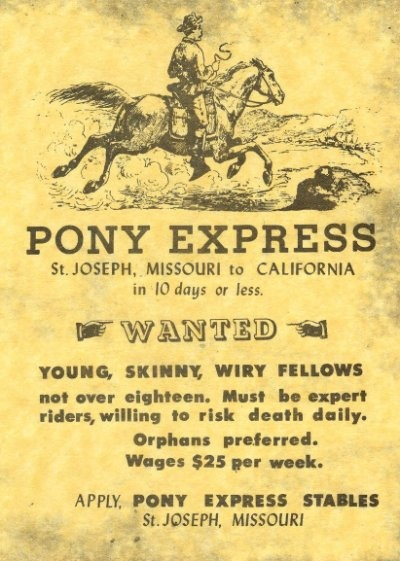

That was the first place I ever saw this PEX “replica poster.”

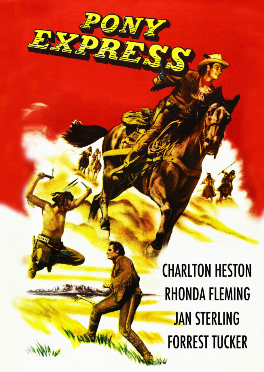

I had heard about the Pony Express in passing since my childhood in the 1950s. It was part of the lore of the Old West that showed up in passing in pop culture such as B-

…(like in the Charlton Heston movie poster above from 1953) as mature, macho guys in their 30s or 40s.

So what was this about “orphans” and “under 18”??

By the time I got back from that trip, I’d forgotten all about the poster, so never got around to looking into the topic. Only recently did I think to google the history of the Pony Express.

The first thing I learned was that the “historical poster reproduction” I’d seen was actually a “historical FICTION” item. Although the poster shows up all over the Internet, most folks admit that it is not based on any actual document remaining from the heyday of the Pony Express. It is a faux poster.

But the second thing I learned was that the information on the poster wasn’t ALL that far from accurate regarding the nature of the Pony Express. More on that later in this blog entry.

The third thing I learned was that I had entertained for my whole life a false notion that the Pony Express was a major feature of American life of the second half of the 19thcentury. I never thought through how long it may have been in business, but I had been left with the impression that it had been around for, oh, say 50 or 60 years. Instead I learned that it lasted a total of barely 19 months! The first riders headed out on the cross-

Nineteen months?? How on earth did the institution get such a major and enduring reputation based on a run of 19 months? We’ll revisit that question after we sort through some of the established historical facts about the Pony Express.

Background

Up to 1860, if a person or business on the East Coast of the US (or the US government, for that matter) wanted to get a message to or from the West Coast, they could expect for it to take at least a month or so by ship around the tip of South America (this was long before the Panama Canal, of course), or three weeks minimum (sometimes up to months) via stagecoach. This was a major inconvenience for many businesses, as well as for the government. In 1850, California became a state, but with the communication lag, it was difficult for it to take an active part in the nation. This became particularly significant in relation to such things as national elections…and even more critical in the time leading up to the Civil War.

The telegraph had been invented in the 1840s, and telegraph communications spread quickly throughout the eastern US. But the telegraph lines had not yet crossed the country. The young railroad industry grew quickly also, with 9,000 miles of track by 1850. But it would be 1869 before a transcontinental railroad was completed, and mail could be delivered by train. So California was left out of the loop.

Into the gap in 1860 stepped the company of Russell, Majors & Waddell, with a plan to speed mail across the country via a relay system of horseback riders. (Although they dubbed their brainstorm the Pony Express, actually they pressed into service both horses and ponies.)

In 1860, there were about 157 Pony Express stations that were about 10 miles apart along the Pony Express route. [Which was about 1,900 miles total.] This was roughly the distance a horse could travel at a gallop before tiring.

At each station stop the express rider would change to a fresh horse, taking only the mail pouch called a mochila (from the Spanish for pouch or backpack) with him.

The employers stressed the importance of the pouch. They often said that, if it came to be, the horse and rider should perish before the mochila did.

The mochila was thrown over the saddle and held in place by the weight of the rider sitting on it. Each corner had a cantina, or pocket. Bundles of mail were placed in these cantinas, which were padlocked for safety.

The mochila could hold 20 pounds of mail along with the 20 pounds of material carried on the horse. Included in that 20 pounds were a water sack, a Bible, a horn for alerting the relay station master to prepare the next horse, a revolver, and a choice of a rifle or another revolver. Eventually, everything except one revolver and a water sack was removed, allowing for a total of 165 pounds on the horse’s back.

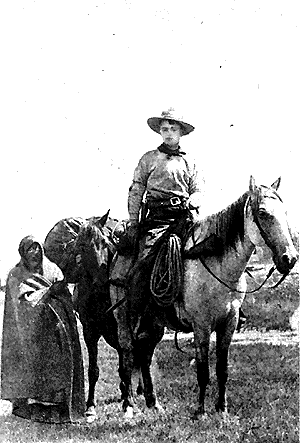

Riders, who could not weigh over 125 pounds, changed about every 75–100 miles, and rode day and night. In emergencies, a given rider might ride two stages back to back, over 20 hours on a quickly moving horse.

And there’s where you get those under-

In fact, it wasn’t unheard of for kids as young as 11 or 12 to run away from home and try to join the ranks. Some succeeded. Especially if they had no family in the first place and were perhaps living in a foster home under rough conditions. Some riders ended up making good money and moving on to productive lives after the closing of the Pony Express business. Some didn’t.

Billy Tate was a 14 year old Pony Express rider who rode the express trail in Nevada near Ruby Valley. During the Paiute uprising of 1860 he was chased by a band of Paiute Indians on horseback and was forced to retreat into the hills behind some rocks where he killed seven of his assailants in a shoot-

I don’t know how old Frank Webner, the Pony Express rider in this picture, was when it was taken. But by the looks of his “baby face,” I’d put him about Billy’s age.

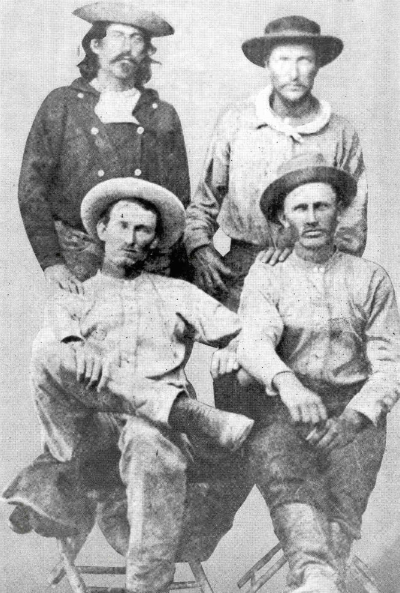

There were older riders though, as you can see from this photo. The two fellows in the back were among the first men to ride the trail, and the two fellows seated were later riders. All look to be at least 30 or older. They just must all be pretty “small and wiry”!

My dad was a US postal worker with a rural mail route for much of his life up to retirement in the 1980s. He drove a jeep through snow drifts in northern Michigan, getting stuck in the snow out in the country no doubt numerous times each winter. He got up to go to work VERY early in the morning, since he had to sort all the mail before he could get on the road. But he certainly never had to “risk his life” to make sure all the clients on his route got their postcards and birthday cards from friends and family, bills, Sears catalogs, and all the rest that we all got—back before email and the Internet!

Those wiry, lightweight men literally did risk their lives over and over (riding for hours through blizzards and other lousy weather much of the time, no doubt)—just so, for instance, some business man in New York City could get some details on shipments from his counterpart in San Francisco. For $5 (later dropped to $1) you could send a .5 ounce letter. You could also send a telegram from New York to St. Joseph, then have it printed out and transported to California by Pony Express. In California it would be delivered to the first telegraph station, which would telegraph its contents on to its destination. That would cost you $3.45 for the first ten words (plus whatever the telegraph companies charged you for their part in the procedure.)

None of this was down in the price range of the average man on the street, of course. In 2013 dollars, the $5 would be about $75. Which would be over two months’ salary for most folks. Probably not that many birthday greetings were sent via Pony Express.

The Pony Express was used frequently by the British Government in forwarding its Asiatic correspondence to London. In 1860, a report of the activities of the English fleet off the coast of China was sent through from San Francisco eastward. For the transmission of these dispatches the British Government paid $135 for Pony Express charges.

The commercial houses of the Pacific Coast cities did not appear to mind a little expense in forwarding their business letters. Often there would be up to twenty-

So it wasn’t a “common” method of communication. But it did do a brisk business for the times.

For the nineteen months that the Pony Express was in service 308 runs were made (westbound and eastbound) for a total distance of 616,000 miles. A total of 34,753 pieces of mail was carried. Of that number 18,456 pieces of mail originated in San Francisco, 4900 originated in Sacramento. At the same time San Francisco received 9553 pieces of mail from the east; Sacramento received 1844. [Source]

And for some fairly significant facets of American history, it was critical.

The Pony Express can be credited with keeping California in the Union during the dark days preceding the civil war when there was a real threat that California would side with the Confederacy. There was some pro-

All through the spring and summer of 1861 the far west followed the tidings of the ebb and flow of battle, calls for volunteers, the Battle of Bull Run, and the lists of dead, wounded and missing. Because of the rapid communication afforded the military and the timely delivery of news of early Union victories, California and its gold stayed in the Union. [Ibid.]

Although the Pony Express did a lot of good for the short time it was active…it didn’t do a lot of good for its owners. Throughout the whole period it was in service, the PEX only grossed about $90,000—which barely paid for the purchase of the horses used. By the time it went out of business, its owners took a loss of $200,000. So it’s probably just as well that it didn’t have to keep struggling to “stay alive.” The PEX didn’t close up shop specifically because of the losses…it closed down because it was no longer needed. The first transcontinental telegraph line connecting Sacramento and Omaha, Nebraska went into service on October 24, 1861, (other lines already connected Omaha and points East) and two days later the Pony Express closed its doors.

So back to that question from the early part of this blog entry: “How on earth did the institution get such a major and enduring reputation based on a run of 18 months?”

I think most folks would agree that it was just that it was such a unique, brash undertaking, and fit so well into the “Romance of the Old West,” that its story was easily adapted as fodder for books and paintings…and eventually motion pictures and TV. Oh… and not the real story of the Pony Express. The hyped-

The Pony Express was short-

Both Russell and Waddell died within a decade of the end of the Pony Express and never wrote a word about their exploits. Majors, an honest-

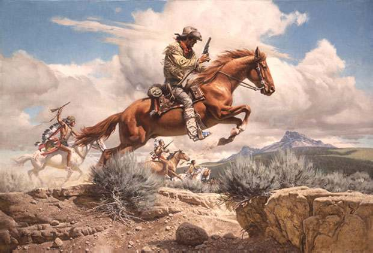

Despite the best efforts of enthusiasts, we are not even sure exactly who rode for the Pony Express. Majors said that he had 80 men in the saddle, but this was not the modern American space program. It seems plausible, and many personal anecdotes support this theory, that just about anyone could ride for the Pony if they were available and the Pony needed a rider. Dramatic images (and every painter in America from Frederic Remington to those who wished to be Remington painted the Pony Express) always show a rider at full gallop pursued by Indians or desperadoes.

[Such as this Pony Express painting by Western Artist Frank McCarthy (d. 2002)]

But the few remaining riders who were actually interviewed late in their lives never mentioned Indians or desperadoes. They always complained about the weather, understandable if you were riding a horse across western Nebraska or Wyoming in January at night in a snowstorm.

They also complained bitterly about not being paid. Russell, Majors & Waddell were notorious deadbeats. Wags in the American West claimed that the initials C.O.C.& P.P. [for Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company, the Pony Express’s “parent company”] actually meant ‘clean out of cash and poor pay.’ [Source]

So even that fabulous $25 a week was more fable than fact.

Yes, it seems that the lore of the Pony Express as it made its way into the movies and TV—and even to having its own modern postage stamp…

…has been based a lot more on the kind of “tall tales” similar to Pecos Bill and Paul Bunyan than on solid research. Consider the very first author who introduced the lore to the American reading public:

The first chronicler of the Pony Express was Colonel William Lightfoot Visscher, a peripatetic newspaperman (but not a colonel) who drifted across the American West in the late 19th century. He is, on reflection, a perfect chronicler for such a tale. He never let the facts get in the way of anything he wrote. Visscher’s book A Thrilling and Truthful History of the Pony Express was published in 1908, nearly half a century after the Pony Express went out of business. Anyone wondering how the story of the Pony Express became muddled need only consider that it took half a century to write a book about the subject, and its author was a dubious chronicler.

Much of Visscher’s research appears to have been conducted at the bar of the Chicago Press Club, his legal address for many years. A terrible liar, a drunkard, a bad poet and a rascal, Visscher bore an amazing resemblance to comedian W.C. Fields. The colonel was a delightful if completely unreliable historian. We have no idea where he got most of his information, although he appears to have cribbed a fair bit of it from the few early attempts to set down some facts about the Central Overland. Historians of the Pony, such as there have been, have always ignored this jolly old lush, who drank two quarts of gin a day for much of his life but lived to be 82. [ibid]

So it’s probably not wise to give too much credence to the “authenticity” of all those old movies and TV shows about the PEX. But they were no doubt entertaining! Here’s one I don’t remember at all…a TV series that lasted from 1989 to 1992, starring Stephen Baldwin, Josh Brolin, and Ty Miller.

And there was evidently a TV series on the same topic that only lasted one season in 1959.

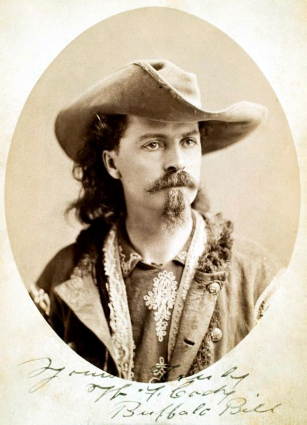

But long before that, it seems that the real “boost” to the popularity of the Pony Express story came in a different venue, the “Wild West Show” extravaganzas put on by the famous Buffalo Bill Cody.

Buffalo Bill Cody (1846-

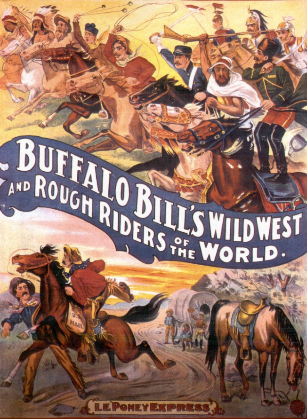

Not only Americans became dramatically acquainted with the Pony Express through Buffalo Bill; Europeans from penniless orphans in London (let into the show because of kind-

Here’s a pic of a poster from a French appearance of Cody’s Wild West…notice the “Le Poney Express” caption at the bottom.

Part of Cody’s enthusiasm for celebrating this bit of the Wild West was that in his youth, he had actually known Alexander Majors [one of the PEX founders]. After Cody’s father died, Majors gave the boy (who was about 11 at the time) a job, riding a pony or a mule as a messenger for the freight-

He did, however, do a great deal for the memory of the Pony Express. Without his devotion, it is unlikely that anyone would remember the horseback mail service. Because of Buffalo Bill, people who did not speak a word of English knew what the Pony Express was. Even today there are Pony Express clubs in Germany and Czechoslovakia, reminders of Buffalo Bill’s legwork on behalf of the fast mail.

So there you have it. An almost “flash in the pan” venture that ended up a permanent fixture in American folklore!

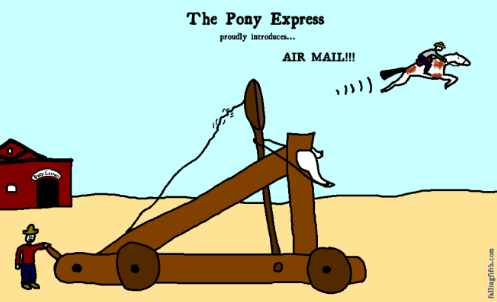

But before closing, we don’t want to forget to pay homage to that little known and seldom mentioned PEX venture that didn’t quite work out as expected either…

The Pony Express Air Mail Service

If you enjoy reading about this era in history,

there’s lots more fascinating information about the PEX on the historynet.com website.